Why it’s hard to muster even a ‘meh’ over Trump’s New York criminal trial

- Share via

In watching some of the breathless coverage of Donald Trump’s “hush money” trial, I’m reminded of the 2004 quote from former U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld that, “You go to war with the Army you have, not the Army you might want.” People want the hush money case to be the big case that can take down Trump because it may be the only one that goes to trial before the election.

Special counsel Jack Smith’s election interference case pending in Washington is the most important of the Trump cases; it may be the most consequential court case for democracy in the history of the United States. The former president is alleged to have tried to subvert the outcome of the 2020 election through fraud, to turn himself from an election loser into an election winner. Similar damning allegations appear in the Georgia state election interference case. And the charges against Trump in a federal court in Florida for allegedly mishandling and failing to turn over classified documents are quite serious.

Trump faces the first of four criminal trials that will cut into his campaigning. He is accused of falsifying records to hide payments to a porn actor.

But the hush money case that opens Monday in New York? I have a hard time even mustering a “meh.” Trump may not be convicted of a felony in the case, and if he is, there’s a reasonable chance of an eventual reversal on appeal. Besides, the charges are so minor I don’t expect they will shake up the presidential race. They may actually make that situation worse.

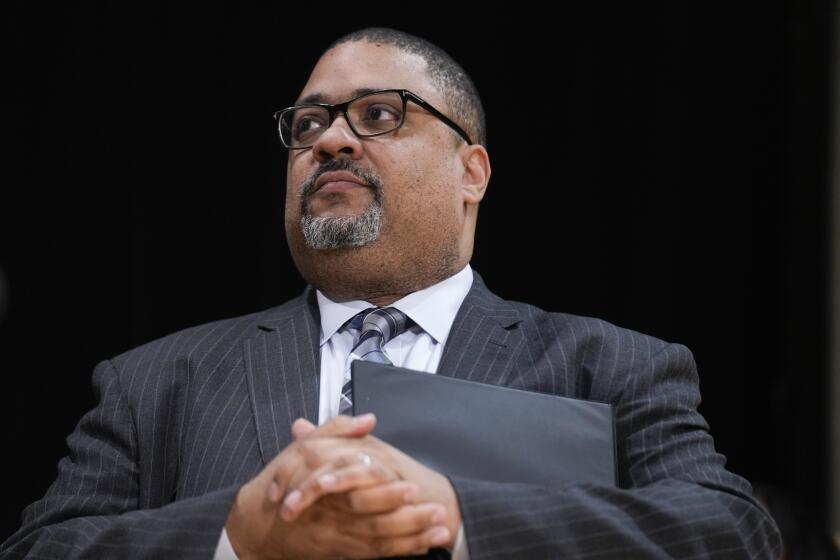

In a nutshell, the allegations are that Trump falsified his business records, using corporate funds funneled through his former lawyer Michael Cohen to pay off adult film star Stormy Daniels to keep her quiet about having had sex with Trump. These falsified business records are almost certainly a misdemeanor, and Trump as a first-time offender would be very unlikely to face jail time for them if this was all that there was to it. But New York Dist. Atty. Alvin Bragg is trying to prove that Trump committed a felony by falsifying the records to further or conceal another crime — in this case a violation of election law or tax law.

Although the New York case gets packaged as election interference, failing to report a campaign payment is a small potatoes campaign-finance crime. Willfully not reporting expenses to cover up an affair isn’t “interfering” with an election along the lines of trying to get a secretary of state to falsify vote totals, or trying to get a state legislature to falsely declare there was fraud in the state and submit alternative slates of electors. We can draw a fairly bright line between attempting to change vote totals to flip a presidential election and failing to disclose embarrassing information on a government form. If every campaign finance disclosure violation is election interference, our system is rife with it.

Alvin Bragg’s New York indictment suggests a cover-up of federal crimes. It’s not unusual for a crime in one jurisdiction to be attempted or hidden in another.

I certainly understand the impulse of Trump opponents to label this case as one of election interference — that could resonate with voters and make them less likely to vote for Trump. But any voters who look beneath the surface are sure to be underwhelmed. Calling it election interference actually cheapens the term and undermines the deadly serious charges in the real election interference cases.

The tax charges may be a stronger path toward turning this into a felony, though there is doubt about that too.

Felony conviction based on furthering or concealing either crime turns on Trump’s state of mind. Was his purpose in falsifying the records to hide other crimes or keep the information from his wife? It’s possible all 12 jurors will believe he falsified records for illegal purposes. But if even one juror doesn’t, it means a hung jury and no conviction. Remember that former presidential candidate John Edwards was tried on similar charges related to an affair, and it led to an acquittal on one charge and a hung jury on others.

A New York grand jury investigating hush payments made on Donald Trump’s behalf during the 2016 presidential race spotlights prosecutor Alvin Bragg.

Anything less than a felony conviction would only embolden Trump. He has already convinced a chunk of Republican voters that all the claims against him are a “witch hunt”; a hung jury or acquittal, or even a conviction on minor charges, would only feed the lie that all the indictments he’s racked up are bogus.

Trump also may have serious grounds for appeal in the New York case. It is far from clear that appellate courts would treat the hush money payments as legitimate campaign expenses that needed to be reported, as opposed to personal expenses. And it is uncertain that failing to report a campaign expenditure required by federal law can be a violation of New York state election law against promoting “the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means.” These issues may well have to be sorted out by higher courts.

The Supreme Court through its timing could well deprive us of the trial we need to give voters important information about the next election — whether Donald Trump tried to steal the last presidential election. The New York case is not a worthy substitute.

Richard L. Hasen is a professor of law at UCLA. His latest book is “A Real Right to Vote: How a Constitutional Amendment Can Safeguard American Democracy.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.