What does Los Angeles owe the people who lost their homes in Chavez Ravine? More than an apology

- Share via

Before Chavez Ravine became the sun-dappled baseball field of the Los Angeles Dodgers, it was a different field of dreams for the homeowners who made a community there.

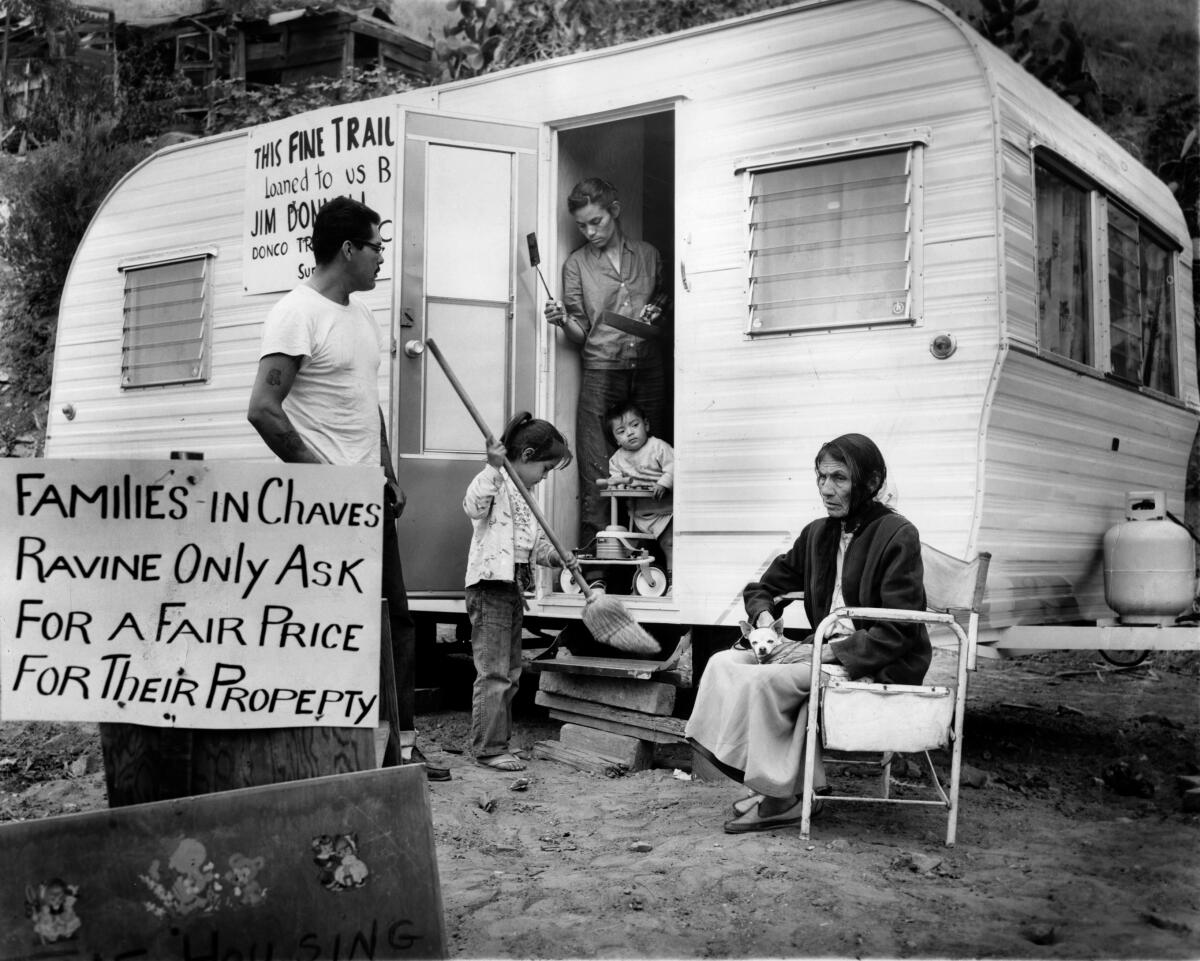

In the hills north of downtown Los Angeles, mostly lower-income Mexican Americans as well as a number of other nonwhite and immigrant families bought homes in the neighborhoods of La Loma, Bishop and Palo Verde. Barred by racial covenants and other discriminatory practices from living and buying elsewhere in the city, they turned the 315 acres of Chavez Ravine into a thriving, close-knit enclave with stores, churches and a school.

To L.A. city officials, the neighborhoods looked poor and blighted. (It would have helped if the city had provided better services.) Los Angeles Housing Authority official Frank Wilkinson came up with the idea to turn the area into a shimmering new public housing project that would be called Elysian Park Heights. In 1950, to make way for this vision, the city began a fraught, decade-long process to get people out of their homes by offering what were considered below-market cash offers or by taking properties through eminent-domain proceedings.

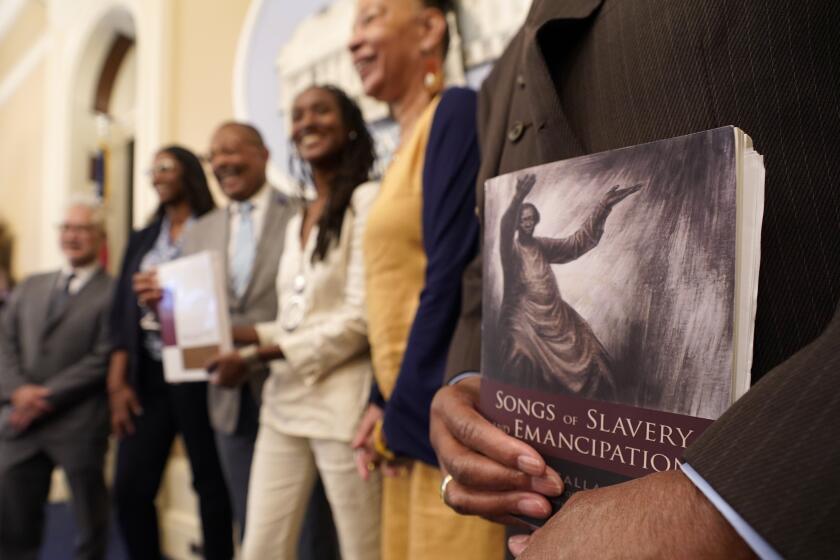

The reparations task force has been working for two years on a plan to readdress the generational effects of racism and slavery on Black Californians. Their report must not get shelved. This is too important.

Even before the last residents were forced out, the public housing project was abandoned. In 1957, the city agreed to trade the Chavez Ravine land to Walter O’Malley, owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, for a minor-league baseball field he owned in L.A. The destruction of the community and the unjust treatment of its residents is a blight on L.A.’s history far worse than the condition of the neighborhoods torn down.

Now, a state bill would give the city a chance to address what it did to Chavez Ravine residents. Assembly Bill 1950, the Chavez Ravine Accountability Act, authored by Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo (D-Los Angeles), would give descendants of the affected families — and any surviving residents — what she says is “fair and equitable compensation.” The bill is part of a growing movement for reparations for people whose property was unjustly taken over the decades. In this case, Carrillo said, “Communities have been robbed of generational wealth” by the taking of their homes.

Liberal and conservative justices seemed to grasp the cruelty and futility of fining or jailing people simply for sleeping outdoors when there aren’t enough shelters.

The bill would require the creation of a task force to figure out how many descendants are due compensation, what is fair compensation for each depending on what they received at the time, how they should be compensated now and what the city could afford to pay in reparations. An estimated 1,800 families, or 3,600 individuals, were displaced. But it isn’t clear exactly how many people this will affect or how much it would cost the city.

The fact that the task will be daunting shouldn’t stop the city of Los Angeles from making amends to the displaced families of Chavez Ravine. The ultimate question is what responsibility the city and state have to do right by anyone who had land, wages and opportunities taken from them by the government ostensibly for a public good. The return of Bruce’s Beach to the descendants of Willa and Charles Bruce, a Black couple whose Manhattan Beach resort was taken from them through a ridiculous eminent-domain claim in 1924, is an example of what a government should do. Last year, likewise, Orange County returned 6.2 acres to the Acjachemen and Tongva tribes for conservation and cultural use. All we can do is tackle these situations on a case-by-case basis. Governments should be held accountable for their past misdeeds and redress them with more than apologies.

Spewing carbon monoxide across L.A. on the freeway system feeds into a pot of racism and segregation that’s been stewing for nearly a century.

The Chavez Ravine families are believed to have received mostly below-market cash offers for their homes. Kamren Curiel, the granddaughter of Palo Verde landowners, wrote in a 2021 article for LAist that her family was offered $6,450 — for two houses they owned. That was 1952. She calculated that would be $63,398 in 2021 dollars, and today the houses would be worth a million dollars. Whatever the correct price was in 1952, forcing the family to sell robbed them of the ability to hold onto and build wealth from the property. “It was totally unjust,” she told an editorial writer. “They were all totally taken advantage of because they were Mexican. I don’t think they felt empowered or educated enough to speak up for themselves.”

Some had to accept what was given to them through the eminent-domain process, which allows the city to take property for public use as long as the owners are fairly compensated. Some refused to leave their homes until authorities literally carried them out. Some got nothing. All had been told they would get first dibs on returning to the newly created housing.

One reason that the compensation seemed low was that it was possibly only for temporary relocation, since everyone had been promised a return to the new housing development in exchange for giving up their houses, according to Eric Avila, professor of history and Chicano studies at UCLA.

It may not be easy to set up, but a right to housing should be essential in Los Angeles.

In addition to the task force, the bill calls for the city to create a permanent memorial and a database of displaced residents, along with government notices and documentation of payments that people received. The bill specifies several ways to compensate people: offering city land or money to descendants of former homeowners, or various services, healthcare benefits or compensation to residents who were not property owners. Carrillo says it will be up to the city and task force to figure out what reparations are possible.

The targeting of Chavez Ravine was racist in its basic premise: These were poor Mexican Americans whose community was deemed substandard and needed to be torn down. However, there are plenty of cases of eminent domain used throughout the city where lower-income communities, usually Black or Latino, were torn down for some kind of public use — a school, public housing, a road. The city is crisscrossed with freeways that uprooted numerous communities of color while affluent, white neighborhoods successfully fought such projects.

What made this case particularly egregious is that the “public good” was never built. Instead, a community was uprooted for land that went to a private baseball stadium. Carrillo points out that the displacement was the city’s doing. But the Dodgers, she notes, were the beneficiaries. And Dodgers officials certainly knew about the displacement in Chavez Ravine. The city should shoulder the responsibility for amends. But the Dodgers should find a way to give back to the families who sacrificed the land that became the Dodgers’ home.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.