Why Alexander the Great really was better than the average imperialist conqueror

- Share via

Book Review

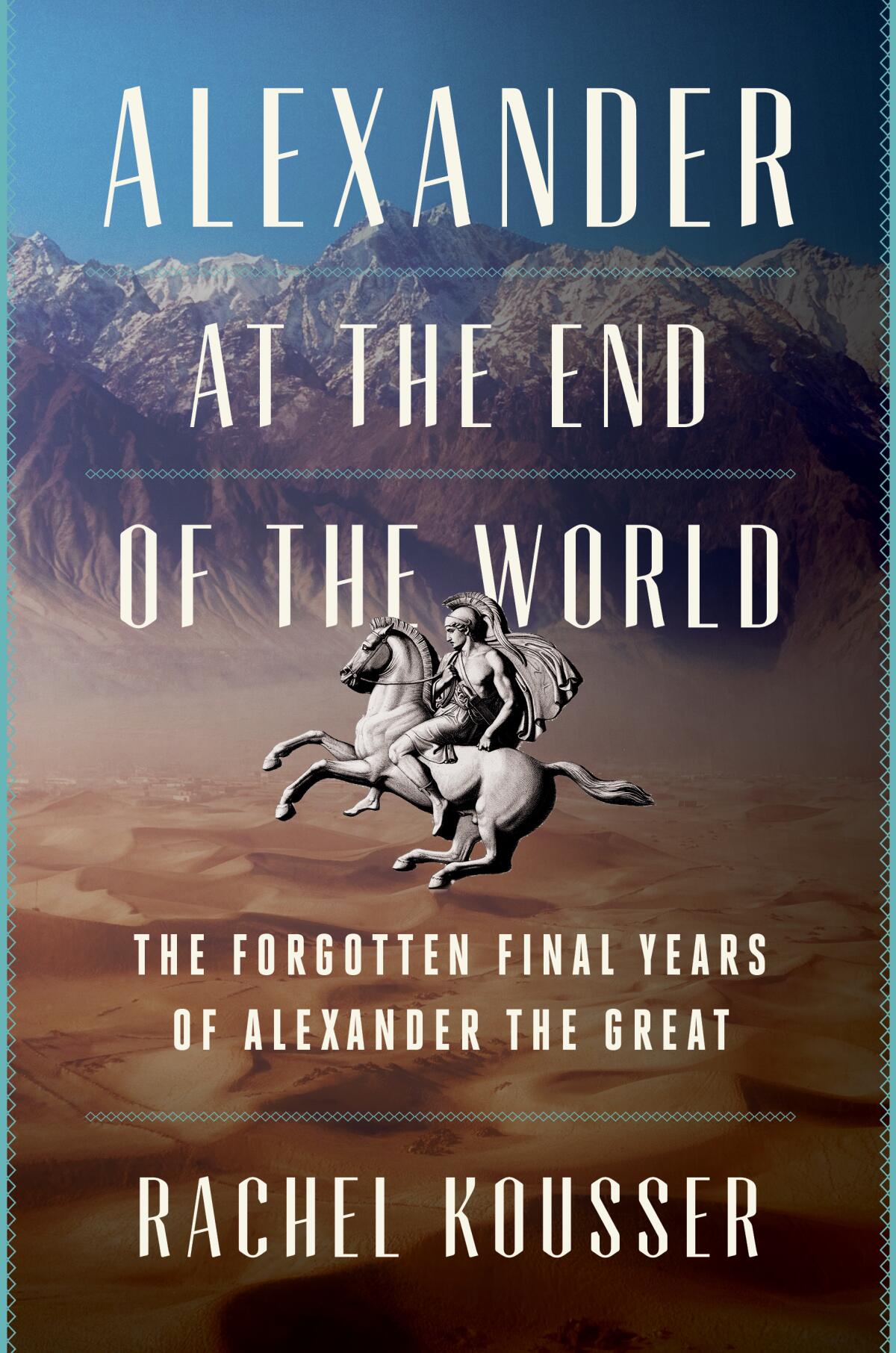

Alexander at the End of the World: The Forgotten Final Years of Alexander the Great

By Rachel Kousser

Mariner Books: 416 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Alexander, the brilliant young Macedonian king remembered as “the Great,” has frequently been compared to the mythic Greek hero Achilles. Both were beloved by their soldiers and almost invincible. But tellings of Alexander’s life have resembled the story of another legendary figure, Icarus, in that his martial skill, good luck and ambition are said to have driven him too far. In trying to reach the end of the world as he knew it, Alexander flew too close to the sun.

The final years of Alexander’s life have often been used by historians to impart any number of moralizing lessons often rooted in anti-Asian racism. Even in his lifetime, Alexander faced criticism that his campaign into Asia corrupted him. As he conquered further lands, the story goes, he became megalomaniacal: unnecessarily violent, easily offended and preoccupied with conquest. In this version of the narrative, Alexander’s offenses piled up to the point that some historians insisted he couldn’t have died of natural causes and must have been assassinated.

Which is why Rachel Kousser’s new biography, “Alexander at the End of the World: The Forgotten Final Years of Alexander the Great,” is a breath of fresh air on its subject. Kousser neatly sums up the myth of Alexander’s “trajectory from upstanding Macedonian monarch to corrupt, violent Oriental despot” and then spends a few hundred pages refuting it.

Critic Bethanne Patrick recommends 10 promising titles — fiction and nonfiction — to consider for your July reading list.

Instead of taking on his entire life — a daunting prospect given that ancient biographies of Alexander sometimes ran to 10 volumes — Kousser focuses on his most maligned years, from 330 to 323 BC, a relatively brief but intense period that solidified his legacy.

Perhaps calling these years “forgotten,” as the book’s subtitle does, is hyperbolic: Alexander’s life was obsessively documented and embellished upon. However, it is fair to say that many historians haven’t given these years their due compared with the glorious days of Alexander’s meteoric rise. These were the years of his losses, failures, near-misses and anticlimactic death.

With ‘Compton in My Soul,’ Albert M. Camarillo shows his Chicano identity is inseparable from his scholarly agenda: expanding the narrative of U.S. history to include folks like him.

Kousser brings us into the story in time for the infamous burning of Persepolis, jewel of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Alexander’s consolidation of power, conquest of Asia Minor and founding of Alexandria were all behind him at this point. When he burned Persepolis, he had just returned from Egypt, where he had proclaimed himself the son of a god.

Alexander’s destruction of the Persian city after cleaning out its treasury is often treated as the beginning of his despotic downfall. But as Kousser shows, he lived to regret the fire. As he pursued conquest across Asia, he quickly learned that godlike fury and scorched-earth tactics weren’t doing him any favors.

It shouldn’t surprise us that Alexander learned new and better ways to rule as he aged. Just 25 when he chased his enemy Darius III, the last Achaemenid king, across Persia, he was hardly old enough to be set in his ways. And yet that’s not how the story is usually told.

Kousser illuminates the many lessons Alexander applied to building his empire. She demonstrates how he learned to negotiate, rein in his impulses and integrate different cultures. Her Alexander is not only cosmopolitan but also trying to create a multicultural empire. Despite his missteps, Kousser writes, Alexander exhibited “grit, resilience, and an open-minded flexibility uncommon for his age, or for any other.”

Nor should it surprise us that this led to conflict with those upholding the status quo. For Greeks convinced of their superiority to people in Africa, Persia and India, Alexander’s egalitarian approach was galling. When his governors undermined him, they were punished not just swiftly but equally, Kousser points out, regardless of background.

Kousser’s biography extends beyond Alexander’s military movements and into his emotional life. She treats his lifelong dream of seeing the edge of the world — and the dashing of that dream — with appropriate emotional weight. She examines his relationship with his friend and general, Hephaestion, and his consuming grief at his death, with the aid of historical context and archaeological evidence. She brings to life the charisma that must have inspired immense loyalty in his soldiers even when they were disgruntled.

And yet Kousser isn’t an apologist. Though she treats Alexander with a compassion that is usually absent from accounts focused on his military achievements, she holds him accountable for his failures. She also details his attempts to rectify and learn from those mistakes.

Importantly, Kousser doesn’t rely solely on Greek accounts of Alexander’s life, which tend to ignore the populations of the places he conquered. Through cuneiform tablets from Babylonian astronomers, Aramaic inscriptions found in modern-day Afghanistan and archaeological remains of his conquests, Kousser teases out the forgotten perspectives of the conquered as much as she considers their conqueror. Her account is exhaustively researched — many chapters extend past 100 footnotes — but remains approachable.

Kousser is above all a professor who has a lesson to teach us. She favorably contrasts Alexander’s attempt at an integrated, multicultural kingdom with later European efforts to “civilize” conquered subjects. Though he was perhaps the proto-imperialist, Alexander celebrated and honored the diversity of the people he conquered.

Though thousands were killed, the survivors were part of the most diverse kingdom in antiquity. Alexander never tried to force conformity to Macedonian culture or religion. He encouraged Persian governance, Indian philosophy and interreligious marriages. In that, Kousser sees a road map to a multicultural future.

Kousser’s work is a much-needed addition to the historiography of Alexander’s life. Refuting the myth of Alexander’s fall, she reveals that the “East did not corrupt the Macedonian king. Instead, from the outset he contained within himself the seeds of everything he would one day become.”

Valorie Castellanos Clark, a writer and historian in Los Angeles, is the author of “Unruly Figures: Twenty Tales of Rebels, Rulebreakers, and Revolutionaries You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.