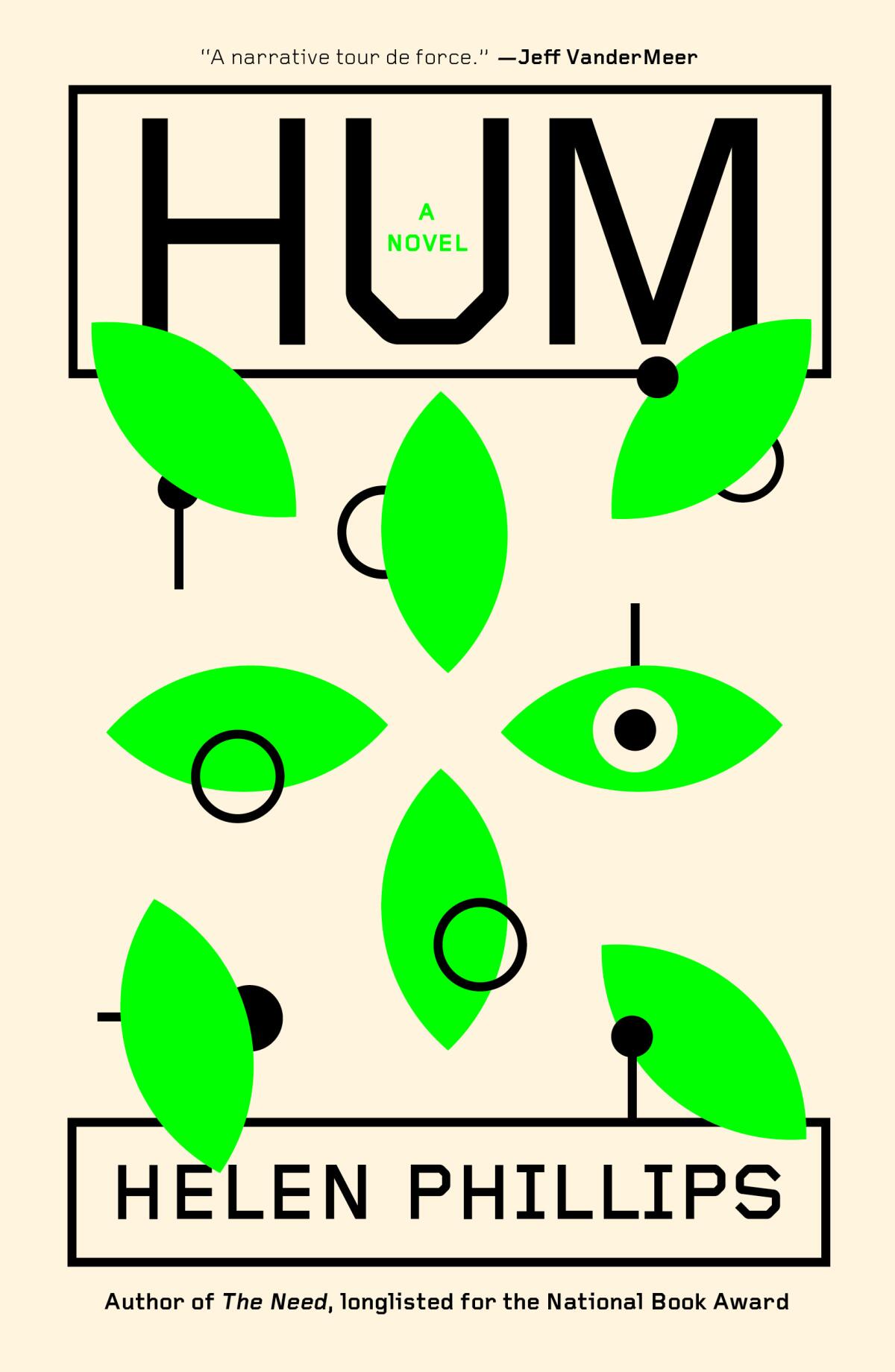

In a treeless dystopia run by robots, glimmers of humanity and hope

Book Review

Hum

By Helen Phillips

Marysue Rucci: 272 pages, $27.99

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There is a doomsday tinge to today’s news that leaves us in a permanent state of high alert. Forest fires rage. Hurricanes hit early and with more severity. Artificial intelligence picks up what we’re thinking. It was even recently reported that the effects of climate change are so profound they’re slowing the speed of the Earth’s rotation, slightly increasing the length of our days, and potentially messing with the computer systems that control GPS navigation and the power grid. Is it any wonder, then, that contemporary fiction is rife with work that imagines what it would be like to survive the end of the world as we know it?

In “Hum,” Helen Phillips has written an eerie and electric novel that blurs the lines between dystopia and reality. What makes this especially creepy is how masterfully she taps the sense we feel in our own lives that what was once the stuff of sci-fi has seeped into the everyday. An existential anxiety hangs over her protagonists, which in turn infects the reader. And while this is not a pleasant sensation, Phillips’ skills as a stylist and keen observer of human nature keep us feverishly turning pages. And her unexpected humor lightens the mood.

Protagonist May Webb and her family occupy a treeless, overheated planet that feels post-apocalyptic, yet there has been no apocalypse — like something straight out of Dr. Seuss’ “The Lorax”: What has rendered their urban landscape bleak and quasi-inhabitable is a gradual, toxic combo of global warming, consumption culture and technology — though the latter is also what enables “normal” life. AI-powered robots, known as “hums,” are as numerous as people, filling essential jobs and programmed to offer patiently delivered advice on any problem, along with verbal prompts to buy things that algorithms suggest will tempt consumers.

We encounter our first hum on the first page. It’s wielding a surgical instrument that will subtly but permanently alter May’s face so she will no longer be identifiable to the devices surveilling city dwellers. May’s sole reason for opting to be a guinea pig in this startup’s experiment is monetary: She’s unemployed (replaced by a hum), and going under the knife will net her the equivalent of 10 months’ salary. Casting aside her own doubts about the operation — and those of her husband, Jem — she hopes the influx of cash will ease the family’s financial woes and that her appearance won’t change so drastically her kids will be unable to recognize her. In the novel’s opening scene: “The needle inched closer to her eye, and she tried not to flinch. ... The hum paused to dip its needle-finger in antiseptic yet again, then re-extended its arm, a meticulous surgeon.” When it’s over, the hum reassures its patient: “‘Beautiful, May.’ … She sensed that the hum was not declaring her beautiful but rather was reacting to its own handiwork.”

May is mother to two young children — daughter Lu and son Sy — who haven’t known a time when the air was mostly breathable or when their wrists weren’t attached 24/7 to “bunnies,” an extreme version of modern-day smartphones. Not wearing them is verboten; without them, parents and local authorities can’t monitor their physical location and vital bodily functions. Lu and Sy have formed tight bonds with their bunnies and never want to part with them. But craving a family vacation without screen time, May envisions a bunny-free weekend at the Botanical Gardens, a pricey virtual biosphere where visitors can pretend they’re in a real forest. Jem is dubious both about splurging and parting with their phones, but once they enter this cool oasis, with its waterfalls and strawberries and starry skies, all doubts dissolve. After a few days, May and Jem agree the experience has revived them. She remarks: “It doesn’t feel like an illusion to me.” He replies: “That’s why it’s a good illusion.”

But in this alternate yet plausible universe, being offline is not a good idea. Disconnecting from your device equals dropping your guard, and vigilance is required — a painful lesson May learns when her kids wander off and she has no way to track them.

While Phillips is portraying a near-future that many of us can easily imagine, she is also excavating the terrors of motherhood, amid its joys, as she did brilliantly in her acclaimed 2019 novel, “The Need.” Parents have always feared for their children’s safety, but this generation of writers is contending with an array of unknowns that raise the stakes, not the least of which is an epidemic of isolation and loneliness. May’s family retreats at night into individual “wooms,” cocoon-like enclosures that silo them, where they can access memories and streaming services or converse with Siri-like confidants. When May hungers to unlock her withholding husband’s innermost thoughts, she slips into his woom when he’s away to parse his search history.

Ironically, the kindest, sanest creatures in this oddly beautiful novel are the hums, who aren’t subject to the angst and apprehension humans can’t escape. When a hum who comes to May’s rescue visits the Webbs’ apartment, the family seems to forget it isn’t human. May invites the hum to dine with them, and the hum agrees.

“‘Come!’ the children said breathlessly, guiding the hum to the seat at the head of the small dining table. ... ‘We need five place mats,’ Lu announced. ‘Actually, Lu,’ the hum said, ‘I don’t eat.’ ‘Oh,’ Lu said, ‘okay.’ ‘But if you want, I can pretend to eat,’ the hum said.”

Phillips has given us a lot to chew on, but there is also something comforting embedded in this cautionary tale: an homage to our adaptability, our capacity to love and our willingness, however reluctantly, to embrace the new. While nostalgia isn’t in this writer’s arsenal, she is a fierce critic of “progress.” Here she urges us not to surrender our power to choose and to resist, but to be thoughtful warriors, deciding for ourselves how we will dwell on our imperiled planet.

Leigh Haber is a writer, editor and publishing strategist. She was director of Oprah’s Book Club and books editor for O, the Oprah Magazine.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.