- Share via

This month, in a move equally shocking and predictable, the National Endowment for the Arts terminated or rescinded hundreds of previously awarded grants to arts organizations nationwide. Among the California institutions affected are the South Coast Repertory theater company, Los Angeles Theatre Works, the community-based Cornerstone Theater Company and Transit Books, a Bay Area publisher specializing in international literature with authors including Norwegian novelist and playwright Jon Fosse, who received the 2023 Nobel Prize in literature.

“The NEA,” the endowment asserted in a mass emails sent to these grantees, “is updating its grantmaking policy priorities to focus funding on projects that reflect the nation’s rich artistic heritage and creativity as prioritized by the President. Consequently, we are terminating awards that fall outside these new priorities.”

National Endowment for the Arts, facing an existential threat from President Trump, cancels grants for L.A. Theatre Works, L.A. Chamber Orchestra and other groups — some of which already spent the funding based on an NEA recommendation.

Such a criterion is absurd, not least because the recipients in question are part of our “rich artistic heritage.” Many serve as incubators, creating spaces for artists and art making that might otherwise be overlooked. In that regard, they are the most necessary components of our aesthetic infrastructure.

The NEA, of course, has long been a target of this president. During his first term, he repeatedly tried to cut the endowment’s budget but was restrained by Congress. This time, things are different, with the administration hollowing out many of the mechanisms of government, including federal grants and aid across the board. It was only a matter of time, then, before the focus returned to the arts.

I understand why some might consider art dangerous. What is it worth if it hasn’t any teeth? And yet, in all sorts of ways, the arts necessarily represent a nation’s collective soul. The mediums, the artists and what is created remind us of our diversity, and also reflect our commonality, in all its glorious contradiction and complication. The arts make us question ourselves and feel for one another. They encourage us to think.

Apocalypse as a happy ending? Only in Los Angeles. It’s an idea that’s epicentral to the identity of the place.

I also understand there’s a case to be made that artists should not be in the business of taking money from the government. Isn’t accepting federal support a form of complicity? Over the years, I’ve gone back and forth on this, but now I’m off that fence. Why shouldn’t artists be rewarded? Why wouldn’t they deserve taxpayer support? For their own sake, yes, but also because it’s good for everyone. Every grant, after all, carries a host of ancillary benefits — not only to recipients but also to the businesses and services in their communities.

The NEA represents the proverbial rising tide that lifts many boats.

In any event, the grant terminations have nothing to do with questions of purity. They are politically motivated, targeting projects and institutions deemed insufficiently American. The stance is partisan even as it implies art should not be ideological. As George Orwell observed in his 1946 essay “Why I Write”: “The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.”

I was a juror on the NEA’s 2012 literature publishing panel. Many of the grants we awarded — to literary organizations, journals and independent publishers — are similar to those that have been reversed. I recognized then, and continue to believe, that such support is crucial, not only because it is necessary for the financial stability of the recipients but also because it allows us, as a culture, to uncouple art from commerce in fundamental ways.

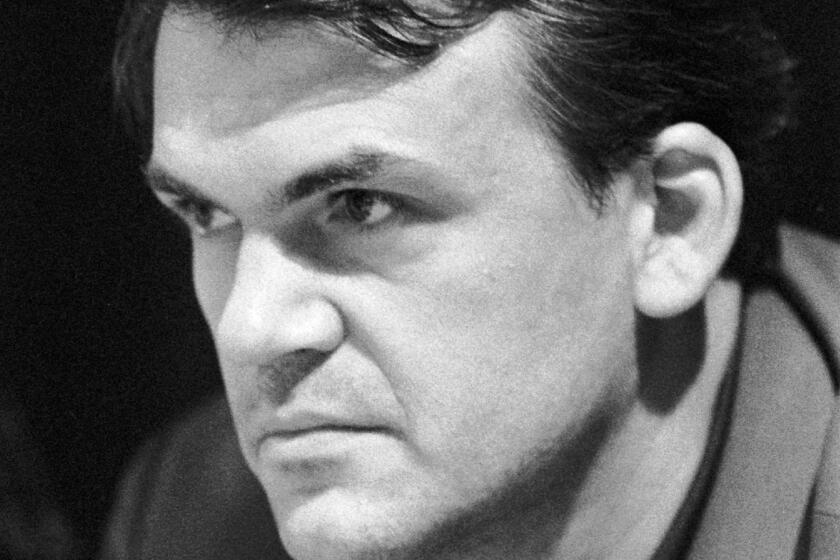

Milan Kundera, the “Unbearable Lightness of Being’ author who died Tuesday at 94, didn’t just liberate minds from tyranny. He freed the novel too.

“It is difficult,” William Carlos Williams wrote in 1955, “to get the news from poems / Yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.” What he’s saying is that to reduce art to a mere commodity, measured by price or practical utility, is to overlook its true worth.

This is what makes the NEA and its grant making so important. Without it, many arts organizations have been, and will continue to be, driven out of business or forced to restrict the scope of their work.

In a May 6 email to subscribers and supporters, Oscar Villalon, editor of the San Francisco literary journal Zyzzyva (full disclosure: I am a contributing editor) responded to the publication’s rescinded grant in the starkest possible terms: “The current mood is one of dreadful anticipation of further hostility toward arts and culture, in general, and toward any institution or organization — nonprofit or otherwise — whose values do not align with the goals of this presidency.”

That this is the point of the exercise should go without saying. At the same time, there is more at stake. The issue is not simply the survival of any one institution but the need to preserve the legacy and lineage of the humanist tradition, which begins with making room for many voices and constituencies.

The most essential art challenges not just our preconceptions but also our perceptions. That’s what makes it necessary. The arts speak for all of us, which means we cannot help but be diminished when they are.

David L. Ulin is a contributing writer to Opinion Voices.

More to Read

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Viewpoint

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

- The article argues that recent NEA grant terminations target institutions integral to America’s “rich artistic heritage,” such as theaters and publishers nurturing underrepresented voices, contradicting the administration’s stated rationale for cuts[Provided Article].

- Federal arts funding is framed as essential for decoupling art from commercial pressures, enabling cultural institutions to prioritize creative and humanistic values over profitability[Provided Article][3].

- The cuts are characterized as politically motivated, aiming to suppress organizations deemed misaligned with the administration’s ideological goals, thereby undermining artistic diversity and free expression[Provided Article][1].

- Economic repercussions extend beyond grantees to their communities, as NEA funding often supports local businesses and services, amplifying its societal impact[Provided Article][3].

Different views on the topic

- The NEA defends its grant prioritization shift as aligning with presidential directives to support initiatives like HBCUs, disaster recovery, and AI competency, asserting these reflect updated national priorities[2][1].

- Conservative critics argue defunding the NEA curbs federal overreach into cultural matters, framing previous grants as supporting partisan or “woke” agendas rather than universal artistic values[1][2].

- Proponents of the cuts contend reallocating funds to trade programs or heritage projects better serves economic and patriotic goals, prioritizing tangible outcomes over abstract artistic endeavors[2][1].

- Some view federal arts funding as inherently politicizing, suggesting private philanthropy or market-driven support could reduce reliance on government-aligned criteria[1][2].

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.