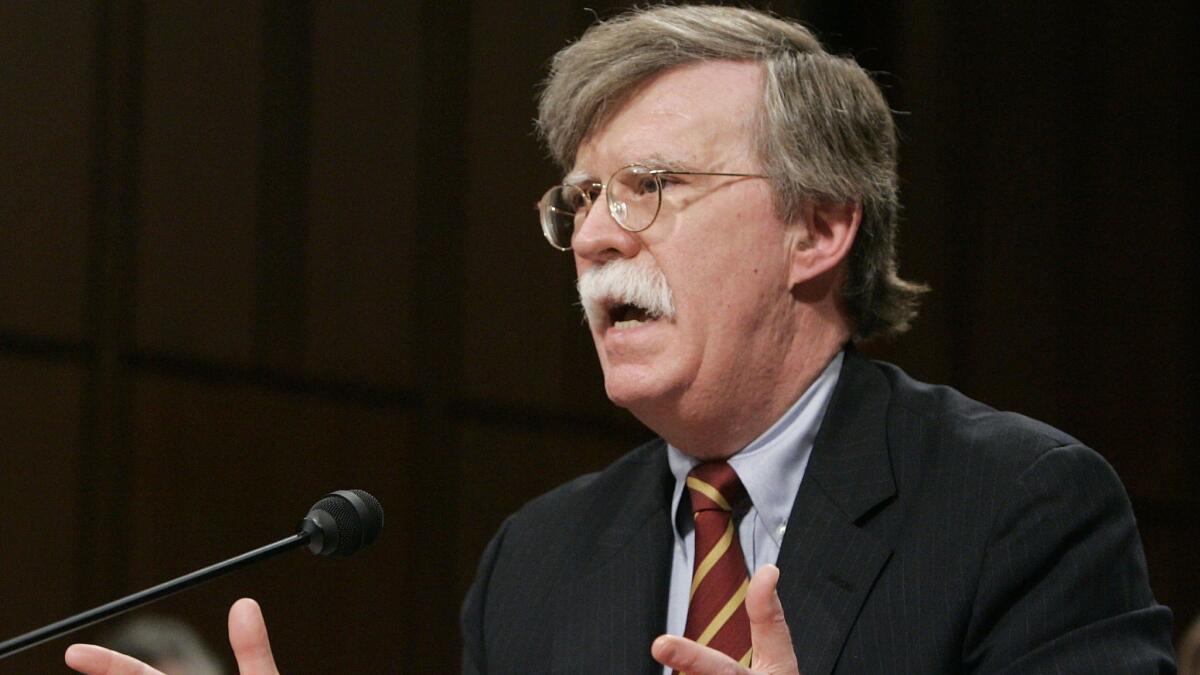

From the Archives: John Bolton is a tough guy with a cause

- Share via

Editor’s note: President Trump announced Thursday that hard-line conservative John Bolton would replace Army Gen. H.R. McMaster as national security advisor. This profile of Bolton was published May 1, 2005, when he served as ambassador to the United Nations under President George W. Bush.

When John R. Bolton charged into the State Department in 2001 as President Bush’s top arms control official, he thought of himself as a loyal Republican soldier on a mission into hostile political territory, according to friends and colleagues.

That assessment became a self-fulfilling prophesy. In the course of the four years Bolton served as an undersecretary of State, he had a succession of ideological and personal clashes with subordinates, colleagues and superiors.

Eventually, Colin L. Powell, secretary of State at the time, ordered his deputy, Richard L. Armitage, to keep tabs on Bolton and prevent him from alienating allies, three current and former State Department officials said. One of the officials said that he was specifically assigned to “mind” Bolton and report back if the undersecretary’s activities were creating problems.

“John was a super-frustrated guy, pinioned at the wrists by Rich [Armitage], held down and clubbed regularly by his own people, and generally nullified by the secretary’s skills at thwarting him,” said one of the former senior officials, a lifelong Republican who said he “despised” Bolton.

Foreign diplomats who have made no secret of their dislike for Bolton said they were told by other State Department officials that they should not assume that Bolton’s hard-line pronouncements on issues such as North Korea or Iran represented administration policy. In public, though, Powell and Armitage unfailingly defended Bolton and denied the existence of a rift.

The pent-up bitterness over Bolton’s record at the State Department exploded after Bush nominated him to be U.N. ambassador last month, stalling his Senate confirmation hearing and inflaming debate in Washington.

In interviews since the hearing, current and former State Department officials at many levels described an atmosphere of suspicion and mistrust spun out of Bolton’s zealous policy initiatives and the efforts of others to thwart him.

Many who described personal and policy conflicts, including Bolton’s supporters, did so on condition of anonymity because of diplomatic protocol or because of the acute political sensitivity of the situation.

Yet some of Bolton’s reported clashes with colleagues and subordinates -- including two ambassadors, three intelligence analysts, a lawyer and at least three senior State Department officials -- are unsurprising given Bolton’s assertive style and the political chasm between the hard-line Republicans with whom Bolton was allied and the moderate Republicans at the helm of the State Department.

“For a conservative, the State Department is enemy territory,” said Danielle Pletka, vice president of foreign and defense policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, the conservative think tank that is Bolton’s alma mater.

“The State Department in a very general sense is manned by Democrats who are hostile to President Bush’s agenda, period.”

State Department officials vigorously disputed this.

But one, who declined to be named and described his political leanings as Democratic, said he believed Bolton must have felt at least some degree of alienation.

“He’s not been in friendly territory for the last four years,” the official said.

Question of Reputation

Bolton’s nomination to be U.N. ambassador stumbled when a scheduled vote by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was unexpectedly delayed last month after Republican senators voiced reservations. Since then, the Bush administration has battled to secure his approval.

Nevertheless, administration officials have had to grapple with Bolton’s reputation among his friends as a blunt truth-teller, and among his foes as an undiplomatic loose cannon. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, who has telephoned Democratic and Republican senators to ask for their support, has emphasized in conversations with at least two senators that as U.N. ambassador, Bolton would be strictly scripted by Washington, three Senate sources said.

“We think that we can control him,” Rice told one senator, two Senate aides said. “If he strays from the reservation, he’s out.”

Sen. Lincoln Chafee (R-R.I.) said Rice “was clear that he was going to work for her.”

A senior State Department official said he could not comment on Rice’s private conversations, but said: “The secretary has made clear she proposed John and she wanted John for the job.... Her message in speaking to others has been consistent: that John Bolton is a team player and that we are all working for the president.”

Within months of Bolton’s arrival in 2001, many State Department officials had pegged him as an adversary, sent by hawkish Vice President Dick Cheney to keep an eye on the more moderate Powell.

A Baltimore native and lifelong conservative who was a student organizer for Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign, Bolton, 56, has worked for former Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) and in the administrations of Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush. The Yale-trained lawyer earned points with the current president by fighting the 2000 Florida election recount.

As undersecretary for arms control and international security, Bolton appeared gratified to hold a senior job at the State Department, and was always in good humor at the 8:30 a.m. daily staff meetings that Powell held with about 40 top officials, said another former official who served with Bolton.

Sometimes Powell would mention the frequent news accounts of infighting between administration moderates and hard-liners, the former official said, and Bolton and Powell would “break the ice and would have a good laugh of it.”

Bolton and his politics were nothing new to allegedly liberal bureaucracies, the former official said.

After all, Bolton had served in the Reagan and first Bush administrations in the U.S. Agency for International Development -- where colleagues presented him with a bronzed hand grenade inscribed to “the truest Reaganaut” -- and in the Justice Department.

He was an assistant secretary of State in charge of U.S. dealings with the United Nations under former Secretary of State James A. Baker III. He was given the job at the request of Helms, Bolton’s political godfather.

“He wasn’t a loner or an outsider. He knew the State Department well and he knew a lot of people well; he had worked with them before,” said the former official. “And he got along with his peers a lot of the time.”

But reviews of Bolton were mixed. Some said Bolton was “wonderful” and a “dream boss,” though others derided him as “a right-wing idiot” who was “over the top.” One European envoy described how Bolton would lecture fellow senior diplomats from allied countries, “in the style of the Soviets in their heyday.”

Many who worked with Bolton at the American Enterprise Institute described him as a formidably hard worker who wasn’t a glad-hander or a “people person” but was courteous and beloved by his staff and colleagues.

“He’s not warm and fuzzy, but he’s loyal and he’s very fair,” said Veronique Rodman, one of 47 colleagues who signed a letter in support of Bolton. “The computer guys signed the letter. He was nice to the little guy ... but he’s not the kind of guy who’s going to stop in the hallway and schmooze, because he’s busy doing something.”

Others said that one of Bolton’s great strengths was that he did not care whether he was liked.

“He’s so focused on his work that he probably wouldn’t notice that somebody disliked him,” said one supporter. “I imagine if you disagreed with him, you’d probably dislike him intensely because he’s so effective.”

Bolton rarely socialized with colleagues at the State Department, and sometimes referred to lower-level staffers as “munchkins.”

“John’s one of those Washington animals where his personality is his job,” said one neoconservative, a Bolton fan who declined to be named.

‘America Firster’

Although Bolton has allied himself with neoconservatives inside the Bush administration, those who have served with him say he is actually an “America first” conservative, dedicated to advancing U.S. interests and rejecting international constraints on U.S. prerogatives.

Bolton is a scathing critic of the United Nations, and helped dismantle or walk away from international treaties opposed by the Bush administration, including a key protocol of the Biological Weapons Convention and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

One issue Bolton staked out for himself was managing the Bush administration’s battle against the International Criminal Court.

Bush in 2002 withdrew the U.S. signature from the ICC treaty approved by former President Clinton. Congress passed a law that same year barring U.S. military aid to countries that ratified the ICC unless they agreed to exempt U.S. personnel from prosecution.

Bolton enthusiastically took on the job of collecting these exemptions from nations.

“John was the driving force and really had his eye on the ball,” one of the former officials said. “It was something the Congress cared about, the Pentagon cared about, the president cared about -- and he was the person who was going to get things done.”

Bolton got the agreements. But in doing so he angered other State Department officials whose job it was to persuade those same countries to do other things Washington wanted -- including, eventually, joining the U.S. in the coalition that attacked Iraq.

“At one point, several of the regional bureaus kind of revolted” over Bolton’s threats to cut off U.S. military aid to countries whose troops were serving on key peacekeeping operations, a midlevel official said.

Bolton’s superiors sided with the regional bureaus and exempted those countries from the requirement.

“The point is, they were all active partners in the war on terrorism or in Iraq,” the official said. “Maybe they didn’t have a lot of troops on the ground, but still.... It did drive all of the diplomats in the bureaus nuts.”

But others said Bolton was being unfairly criticized for playing the “bad cop.”

“Yes, his focus [on collecting the agreements] caused pain when it ran up against other priorities, and there were people who took offense,” said one of the former officials. “He played it pretty hard, and some people didn’t like it. But that’s policy.”

The Sept. 11 attacks catapulted Bolton, who supervised the State Department’s Bureau of Nonproliferation, onto the front lines of the administration’s drive to keep weapons of mass destruction out of the hands of terrorists.

“Before [Sept. 11], his job was more circumscribed,” the neoconservative ally said. Afterward, “his job was to handle the conservatives’ red meat issues inside the State Department that the administration wanted him to -- and on top of that, that Powell didn’t want to handle himself,” the ally said.

“Powell himself found it convenient to have John do that kind of work, because Powell didn’t want to be the point guy on missile defense or some of the other issues the conservatives cared about,” he said.

Bolton, who had made a career of being tougher-than-thou on defense issues, began to make speeches and statements asserting that the danger of deadly weapons went beyond the “axis of evil” nations of Iran, Iraq and North Korea to less powerful nations that were hostile to the United States. Bolton told The Times in a 2003 interview that his policy was “zero tolerance” of such threats to American civilians.

Bolton had long been a voracious consumer of intelligence reports. He came to his office at 5:30 a.m. each day and poured through a huge stack of them -- including the sort of raw intelligence that critics say was not vetted and therefore unreliable.

He chose as his chief of staff Frederick Fleitz, a CIA employee who was on loan to the State Department, to help him navigate the intelligence world as well as to ensure that he was not dependent for intelligence information solely on the State Department’s own intelligence arm, the Bureau of Intelligence and Research.

Bolton and Fleitz mistrusted the bureau. Fleitz wrote in e-mail messages, subsequently released by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, that he had expected “monkey business” from the bureau, which would only permit Bolton to use “wimpy” language about the threat posed by a possible Cuban biological weapons effort.

Likewise, Fleitz and his colleagues irritated the State Department rank and file. They were “about as abrasive as [Bolton], and true believers, just as he was -- and clearly had very little patience with State Department bureaucrats,” the midlevel official said.

In 2002, Bolton and Fleitz clashed with an analyst at the intelligence bureau, Christian Westermann. That clash is at the heart of accusations that Bolton attempted to “hype” threats posed by Cuban weapons -- and then intimidate and remove analysts who objected. Bolton denies he sought to get anybody fired.

As tensions between Powell and the Bush administration’s hawks grew more apparent, accusations mounted from some in the Powell camp that Bolton was “a loose cannon.” Armitage was overheard in the State Department bellowing in fury about Bolton’s “freelancing.”

Three sources confirmed that Bolton’s speeches had to be specially vetted by Armitage or Powell’s personal staff because Bolton had become so controversial. Armitage did not return calls for comment.

Some U.S. officials complained that Bolton’s undiplomatic style sometimes backfired, harming U.S. interests.

A U.S. government nonproliferation expert said that in the fall of 2003, Bolton insisted on taking a harsh line against Iran at the board meeting of the International Atomic Energy Agency. The U.S. mission in Vienna, where the agency is based, had been assigned a key task: winning a board vote referring Iran to the U.N. Security Council for action to restrain its nuclear programs.

But energy agency board members from other countries refused to go along. Nevertheless, Bolton instructed the U.S. mission at the agency not to compromise on any of the changes sought by other countries to a draft resolution, the official assigned to “mind” Bolton said.

“Next thing I know, our ambassador ... is calling the secretary or Armitage and saying, ‘What the hell are you guys doing? You’re going to send this train over the cliff!’ ” the official said.

Bolton was overruled.

Bolton was distraught at what he considered a soft-line policy on Iran, and sought to have Fleitz travel to Vienna to sit in on a luncheon meeting of energy agency ambassadors, the official said. But the trip was seen as an attempt by Bolton to keep an eye on the U.S. ambassador there, and was nixed as “highly inappropriate.”

The senior State Department official declined to comment on specifics of the Iran policy flap, calling it an example of the “malevolent gossip” surrounding Bolton’s nomination.

Plowing Ahead

Bolton’s supporters and detractors agree that he is undeterred by setbacks and continues to plow ahead, buoyed by his conviction that he answers to his only client -- the president.

“John traveled constantly,” said Pletka. “People like to think of him as this knuckle-dragger sitting in his cave scratching out screeds, but he was really out there promoting the policies.”

Despite -- or perhaps because of -- the frictions between Bolton and Powell, who was accused by conservatives of being insufficiently supportive of the Bush agenda, Bolton is seen by the White House as having done a good job at the State Department under difficult circumstances.

But Rice made it clear from the outset that she did not want to give Bolton the job he wanted -- deputy secretary of State. Rice named Robert B. Zoellick as her deputy, and Robert G. Joseph, a hard-line National Security Council official whom Cheney regarded highly, was nominated to replace Bolton.

For several weeks, rumors swirled among administration-watchers about where Bolton would land.

When he was nominated as U.N. ambassador, Republicans and Democrats alike speculated that Rice had wanted to move him to a job where he would have less input on policy and more reason to follow instructions. And his critical stance toward the United Nations dovetailed with the administration’s thinking.

“I think she pretty much got her way on almost all of her appointments, and like Cheney, she probably thought John deserved something,” said the neoconservative Bolton ally. “Or maybe she didn’t have a choice.”

As the battle over Bolton’s nomination heads toward a crucial May 12 vote in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the White House and Senate Republicans have signaled that they are preparing to fight for Bolton.

“I never expected the president to back away from his support,” said Chafee, who had not made up his mind on Bolton earlier this week. “They knew that it was going to be controversial from the get-go -- that we would have to walk through fire to get it done -- and that is what happened.”

Efron is a former Times staff writer. Former Times staff writers Mary Curtius, Doyle McManus and Tyler Marshall in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.