Column: Political Road Map: Just 3% of California recall elections actually work. They have one thing in common

Reporting from Sacramento — Firing a politician, months or even years ahead of their next campaign for elected office, is the ultimate act of voter anger. And California voters gave themselves the power to do so 106 years ago this month.

In all that time, two things have stood out about recall elections: They rarely succeed, but when they do, it’s usually because of a political fight that goes far beyond the person whose name is on the ballot.

It’s unclear whether those maxims will hold true for state Sen. Josh Newman (D-Fullerton), the Democratic freshman legislator whose fate may be decided by voters in his Orange County-based district early next year. Newman won an open seat last November by just 2,498 votes in what had been a Republican district.

That also is part of the story of recalls. They’re often launched by backers of the candidate who lost the last election by a razor-thin margin. In the case of the 29th Senate District, the gathering of voter signatures on a petition calling for a recall was almost solely paid for by the California Republican Party.

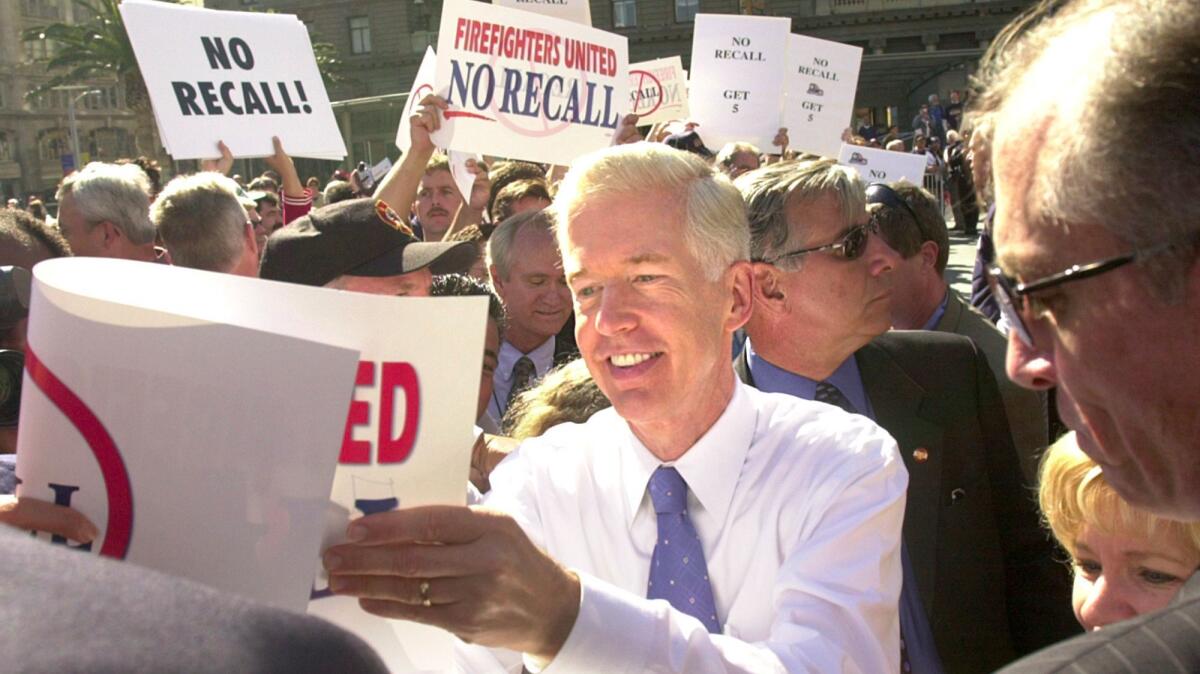

Not counting the Newman effort, there have been 163 attempts to remove California elected officials since 1913, but only nine whose backers collected enough signatures to trigger a special election. In the last 25 years, there are three of note. One — the 2003 recall of then-Gov. Gray Davis and the election of former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger — was a political milestone. The previous winning efforts came following a dramatic power struggle in the Assembly after the 1994 election, when two GOP lawmakers were recalled for helping Democrats retain control over the Assembly.

In 89 other instances over the last three decades, recalls failed to qualify for the ballot. In three other efforts, a special election happened but voters stayed with the incumbent, largely seeing the recall attempts as an overreach.

The successful recalls seemed to hinge on whether the politician in question was the symbol for a larger battle. The two Republican legislators who were removed from office had been painted as traitors to the larger GOP wave that swept the nation that year. In the case of Davis, reelected in 2002 with only a plurality of votes, there was lingering anger over a deep recession and California’s electricity crisis.

But the real fuel was from Davis’ decision to rescind a law that lowered vehicle license fees. The resulting increase, dubbed the “car tax,” was the fatal blow. The tax was easy for voters to understand and fed the narrative of government waste and overspending. It’s an experience Republicans seem to be angling to use again in 2018.

Newman was a key vote in April for a $52-billion transportation plan funded by higher fuel taxes and a new vehicle registration fee. Activists circulated the recall petition while displaying signs that urged a “repeal” of the gas tax (which won’t happen by removing Newman). More than enough signatures appear to have been submitted in the almost evenly split district, which runs from Cypress east to Chino Hills, though the process has been delayed by a law quickly crafted by Democrats this summer to help Newman.

If Newman loses and is replaced by one of the candidates who would be listed on the second part of the recall ballot, he would join a small but infamous California club. The bottom line, as it’s always been for a recall, is whether all public anger will translate into voter action.

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

ALSO

Political Road Map: You’ll get to vote in 2018 on a part of California’s big climate plans

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.