California could bring radical change to single-family-home neighborhoods

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — If you live in a single-family home in California, it’s likely everyone else in your neighborhood does too.

That could change under a state measure that would require California cities and counties to permit duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes on much of the residential land now zoned for only single-family houses. The proposal was recently added to Senate Bill 50, legislation by Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) that also would allow mid-rise apartment construction near mass transit as well as small apartment complexes and town homes in wealthy communities in large counties including Los Angeles.

The bill would not spell the end of single-family housing in the state. Developers could continue to build such homes on their land if they chose, and the legislation prohibits the demolition of single-family homes to build fourplexes without further government review. Even so, allowing as many as four homes on parcels of land where now just one is permitted would trigger significant change compared with how California has grown over much of the last century.

Nearly two-thirds of the residences in California are single-family homes, according to U.S. census data. And between half and three-quarters of the developable land in much of the state is zoned for single-family housing only, according to a 2018 survey by UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation that included responses from half the state’s cities and counties.

The state can no longer dedicate that much land to single-family housing if California is to become more affordable and if political leaders want to meet aggressive goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, said Carol Galante, director of the Terner Center.

“I do not think it’s possible to solve housing affordability problems and meet climate change goals without dealing with this issue of single-family homes only,” Galante said. “We have population growth. We have job growth. People need to live somewhere, and they’re now competing for a very limited supply.”

But doing away with single-family-only zoning would unalterably diminish California for current and future residents, said Zev Yaroslavsky, director of the Los Angeles Initiative at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs and a former Los Angeles County supervisor.

“When people around the world think of L.A., one of the things they think of is a home with a backyard,” Yaroslavsky said. “I think much of it should be preserved.”

High-profile California housing bill clears hurdle after tense debate over local control »

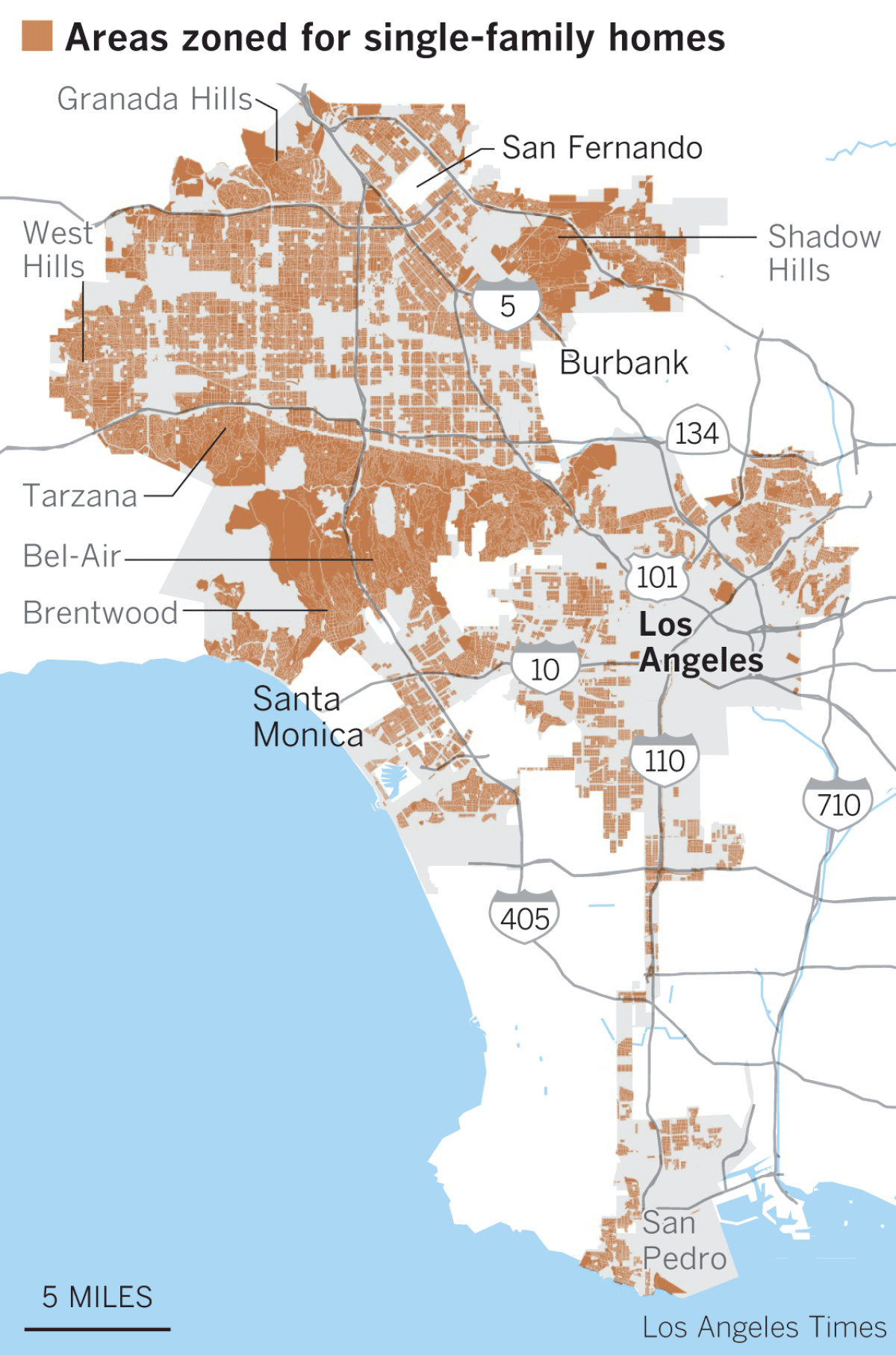

In the city of Los Angeles, 62% of the developable area is zoned for single-family homes only. Neighborhoods such as Tarzana, Bel-Air, Brentwood and Jefferson Park are examples of communities dominated by single-family zoning.

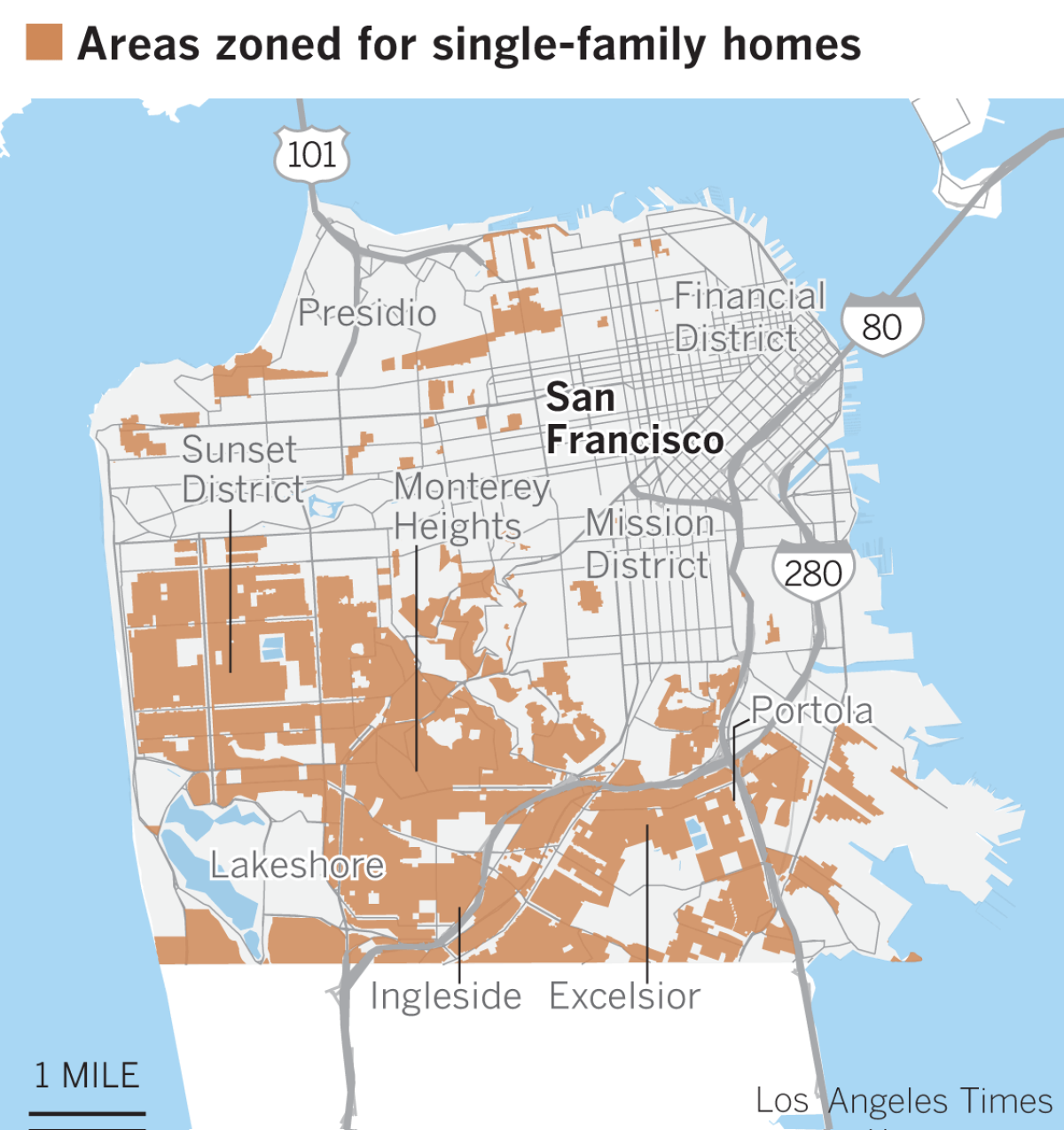

In San Francisco, the percentage of land zoned for single-family homes only is much smaller — about 37% — and includes the Sunset District, Forest Hill, Excelsior, Portola and other neighborhoods concentrated in the city’s south and west.

But by other metrics, the city still reserves a lot of its land for low-density building. Nearly three-quarters of the privately owned parcels in San Francisco are zoned for single-family homes or duplexes only, according to the city’s planning department.

Across the state, communities big and small, wealthy and poor, north and south, coastal and inland have large sections zoned for single-family homes. The wealthy Bay Area town of Atherton sets aside at least 95% of its land for single-family housing, according to the UC Berkeley survey. Between half and three-quarters of the developable land in Sacramento and Stockton is also reserved for single-family homes, the survey said.

Recently, policymakers in California and across the country have scrutinized single-family zoning as housing affordability problems have become more acute.

Three years ago, state legislators passed two bills aimed at making it easier to build small accessory homes in backyards. Since then, applications to build secondary units have increased by the hundreds in Los Angeles, San Francisco and other larger coastal communities.

In some areas in counties with more than 600,000 residents, including Los Angeles, San Diego, Orange, Santa Clara and San Francisco, Wiener’s bill would also allow larger apartment buildings on land previously zoned single-family only — though local height limits would remain intact. To qualify for density increases, such neighborhoods would have to be high-income and near quality jobs and public schools.

Mayors in some of California’s biggest cities are considering doing away with zoning that allows only for single-family homes. At a housing forum in the Bay Area last week, Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf and Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg said they supported ending single-family-only zoning in their communities, and San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo said his city was considering doing so. The trio has endorsed SB 50, as has San Francisco Mayor London Breed.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, who hasn’t taken a position on SB 50, told The Times this year he was considering a proposal that would allow triplexes in the city’s single-family communities.

“You could have one generation of a family, their parents, their kids in the back house, all living together,” Garcetti said. “That would probably overnight add about 50% more housing stock to Los Angeles in a way that is also neighborhood compatible.”

Garcetti cited Minneapolis as inspiration for the idea. In 2018, Minneapolis became the nation’s first big city to do away with single-family zoning by allowing duplexes and triplexes on parcels that previously allowed just one home. Conversation there focused on the history of single-family zoning, which originated out of the desire to exclude poor people or nonwhites from certain communities.

In the early 20th century, court rulings blocked zoning rules that explicitly barred nonwhite people from living in certain neighborhoods. But in 1926 the U.S. Supreme Court decided that proposals allowing only single-family homes in neighborhoods were constitutional, even though many supporters of those plans pushed the zoning as a means to segregate their communities, according to the book “Segregation by Design” by Jessica Trounstine, an associate professor at UC Merced.

In addition, racist deed covenants barred people from selling homes to nonwhites, and government-sponsored lending practices provided low-cost mortgages only to whites through the middle of the 20th century.

Some single-family neighborhoods have changed over time — many communities in South L.A., for example, that once were reserved for whites are now home to predominantly black and Latino residents. But the exclusionary effects of single-family zoning remain today, especially between low-density suburbs and their higher-density neighbors, Trounstine said.

“Communities with a predominance of single-family homes still contribute to race and class segregation,” she said.

Trounstine believes that even if SB 50 passes, wealthier single-family-only communities will still take advantage of the bill’s restrictions or use other political or legal means to ensure their areas remain as they are.

As it stands, the bill has limits on where developers could build fourplexes. Under the legislation, developers would not be able to demolish a single-family house to build a fourplex without local government approval, but a single-family home could be remodeled into a fourplex if it doesn’t increase in size by more than 15%. The bill also places restrictions on building fourplexes in single-family areas that are in flood plains, communities at high risk of wildfire and some historic zones.

These limitations would blunt the bill’s ability to spur construction of fourplexes in single-family-only neighborhoods, says Mott Smith, a principal at Civic Enterprise Development in Los Angeles. But he still expects a significant number of property owners to be able to take advantage.

“I wish that it were less restrictive,” Smith said. “But at the same time, this is quite momentous: the abolition of single-family zoning in California.”

The fourplex provision in SB 50 and the rest of the bill are likely to face additional changes if it moves through the Legislature. The bill faces a May 31 deadline to advance from the state Senate, and it has to clear both houses of the Legislature by mid-September.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.