How should California spend $180 billion-plus? Here’s what is under negotiation in Sacramento

- Share via

The odds are high that by the time June 15 comes to an end, a new state budget blueprint will be sitting on Gov.

That’s the deadline in the California Constitution, one that’s not been missed since voters changed the rules almost seven years ago, ending a generation of summer stalemates in Sacramento.

The changes have empowered dominant Democrats to craft budgets as they see fit, though a few battles remain over spending priorities. Here’s what will probably be the deal makers, or breakers, once the plan for spending on schools, prisons, healthcare and other big-ticket items for the next fiscal year is set in stone.

How much will Democrats buy in to Brown’s economic caution?

Lawmakers and their staff members don’t like to admit it, but a key part of the governor’s success in constraining government spending growth has been his domination over tax revenue forecasts. For six straight years, California’s state budgets have been built on Brown’s cautious economic predictions — and not the more optimistic ones made by the Legislature’s own analysts.

This year, there’s a new twist: Both the state Assembly and

Keep an eye, too, on how the final agreement counts the sources of money for K-12 schools and community colleges. While all sides are in agreement on how much schools will receive next year, lawmakers believe property tax collections are strong enough to offset the use of hundreds of millions of dollars in personal income tax revenues. That’s one way the Legislature hopes to pay for the additional services Brown has said the state can’t afford.

A showdown over proceeds from California’s newly increased tobacco tax

Perhaps the most intense battle is whether the language of Proposition 56 — last fall’s $2 per pack increase in the state’s cigarette tax — has precise mandates on what kind of healthcare services will be covered by the new cash.

The governor believes there is flexibility, and wants to broadly use the money to help fund Medi-Cal, California’s healthcare program for the poor. Democratic lawmakers, advocacy groups and healthcare industry groups that funded the Proposition 56 campaign believe instead that the initiative mandates the money be spent to guarantee — and even expand — access to Medi-Cal.

Key to that, say Proposition 56 supporters, is using the tobacco tax money to boost payments to doctors who treat Medi-Cal patients. California has some of the lowest such payments in the nation, which means some doctors may turn those patients away.

While legislative Democrats rejected the governor’s plan, lawmakers in the Assembly and Senate still have a few important disagreements on how to spend the money.

Comparing the state Assembly and Senate plans for spending Proposition 56 tobacco tax dollars

Senate’s proposal

- $349 million in the fiscal year beginning July 1 on many of the same Medi-Cal items as the Assembly, increasing to $1.1 billion a year by summer 2020.

- Phase in the restoration of benefits the Assembly would fund immediately, reaching annual spending of $85.8 million by summer 2019.

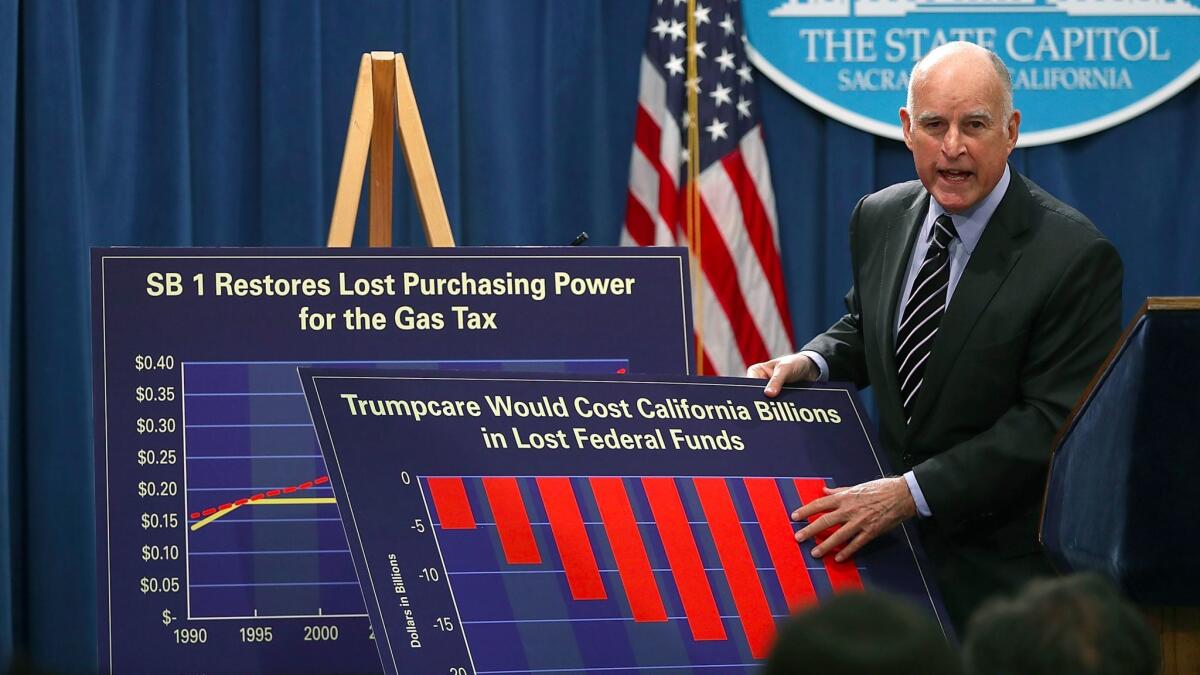

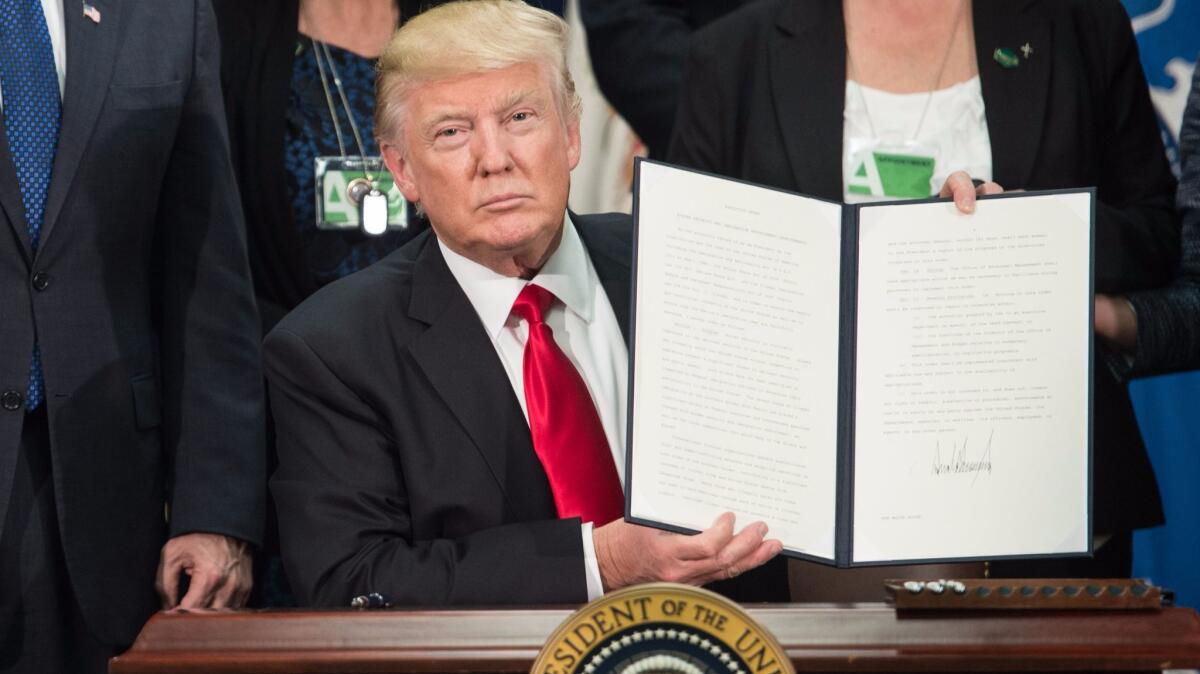

How much will California spend on its resistance to Trump?

No topic has captured the attention of the state Capitol’s supermajority Democrats more than the sharp shift in policy from President Obama to President Trump.

The reaction from California Democrats — fight, oppose and litigate — will cost money. Already, the two houses of the Legislature have spent $100,000 to hire former U.S. Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr.’s law firm as outside counsel, though the Assembly opted last week to let its part of the contract expire.

It’s unclear if the budget will include earmarked money for some of the most high-profile proposals by Democrats to defy Trump — like efforts to subsidize legal assistance during deportation hearings for those in the U.S. illegally.

One provision quietly tucked into the Senate’s budget plan would require the state Department of Justice to “monitor the treatment of immigrants being detained in California.” As of now, no price tag has been put on that effort.

Democrats want more for the poor than Brown seems willing to spend

One of Sacramento’s recurring budget battles centers on the demands of liberal legislators to give more help to the state’s low-income residents, especially through programs that were slashed during the depths of the recession. This year is no different.

Assembly budget writers have included $100 million to pay for inflation adjustments to the state’s welfare assistance program and programs helping the blind and disabled. Those payments were skipped in budget plans from both Brown and the Senate.

Both houses would augment the governor’s budget with more spending on child care programs. And the Assembly seeks $225 million to expand California’s earned income tax credit — a cash payment created in 2015 for those who make too little to pay state income taxes. The program would be expanded to offer cash to the self-employed and those with incomes up to $22,300.

Consensus is near on the University of California, but a clash over middle-class scholarships looms

The most volatile item to watch in higher education funding is just how much budget impact there will be from an April state audit of UC President Janet Napolitano’s spending — including charges of hidden surplus cash in her office’s budget and an effort to keep the unvarnished opinions of campus leaders out of the hands of state audit investigators.

Brown proposed in his May revised budget that $50 million in UC funds be tied to a series of reforms. Legislators want to go further, with the Senate demanding new transparency in Napolitano’s office funds and the Assembly proposing to divvy up some of the UC president’s extra cash.

Less talked about, but just as politically contentious, may be the governor’s effort to phase out the program offering UC and Cal State University scholarships to students from families with incomes and assets of up to $156,000. The program is expected to cost $53 million in the coming fiscal year. The Assembly rejected Brown’s plan last month.

Last year’s leftovers: Affordable housing, preschool funding

A recurring theme in Sacramento this year has been that Democrats in the Legislature believe the Brown administration shouldn’t scrap efforts on two big deals made as part of the 2016 state budget.

As lawmakers continue to grapple with the state’s intractable housing woes, they want to spend the $400 million for affordable housing included in last year’s plan — money that Brown insisted was contingent on approval of a plan that would speed up local government review of new housing projects. But that proposal stalled in the Legislature last summer.

Assembly budget writers now want to use the $400 million to boost housing for those who are homeless or live in transitional housing. Some of the money would also help provide housing for farmworkers and teachers.

Assembly Democrats also insisted the governor make good on a promise for funding to expand access to preschool, and to update income eligibility rules for families that need help paying for preschool. Brown agreed to some of this in his budget revision last month, though it’s unclear whether it’s enough to satisfy his fellow Democrats.

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

ALSO:

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.