After a year of listening, Iowans finally get a say — in their own unique way

- Share via

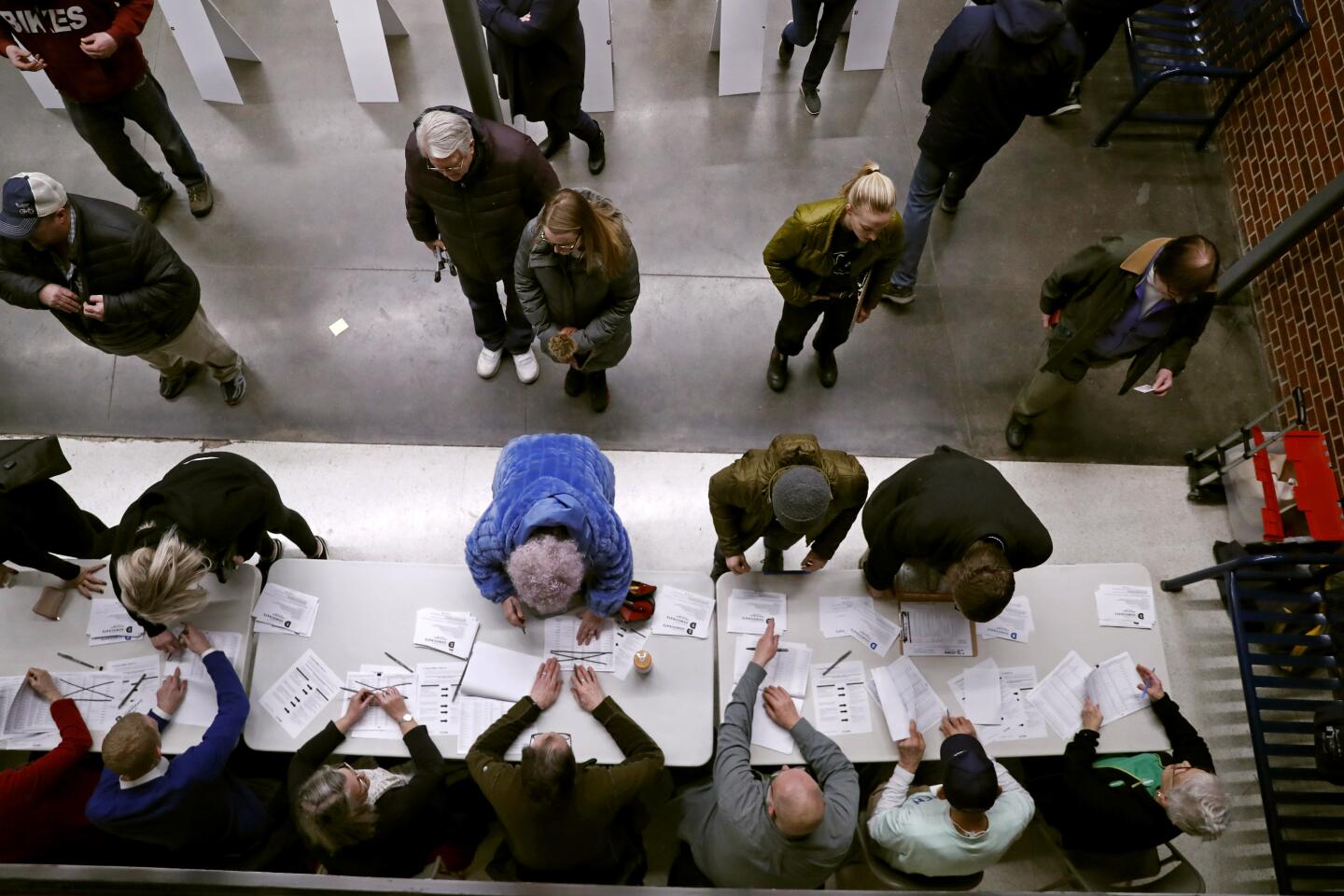

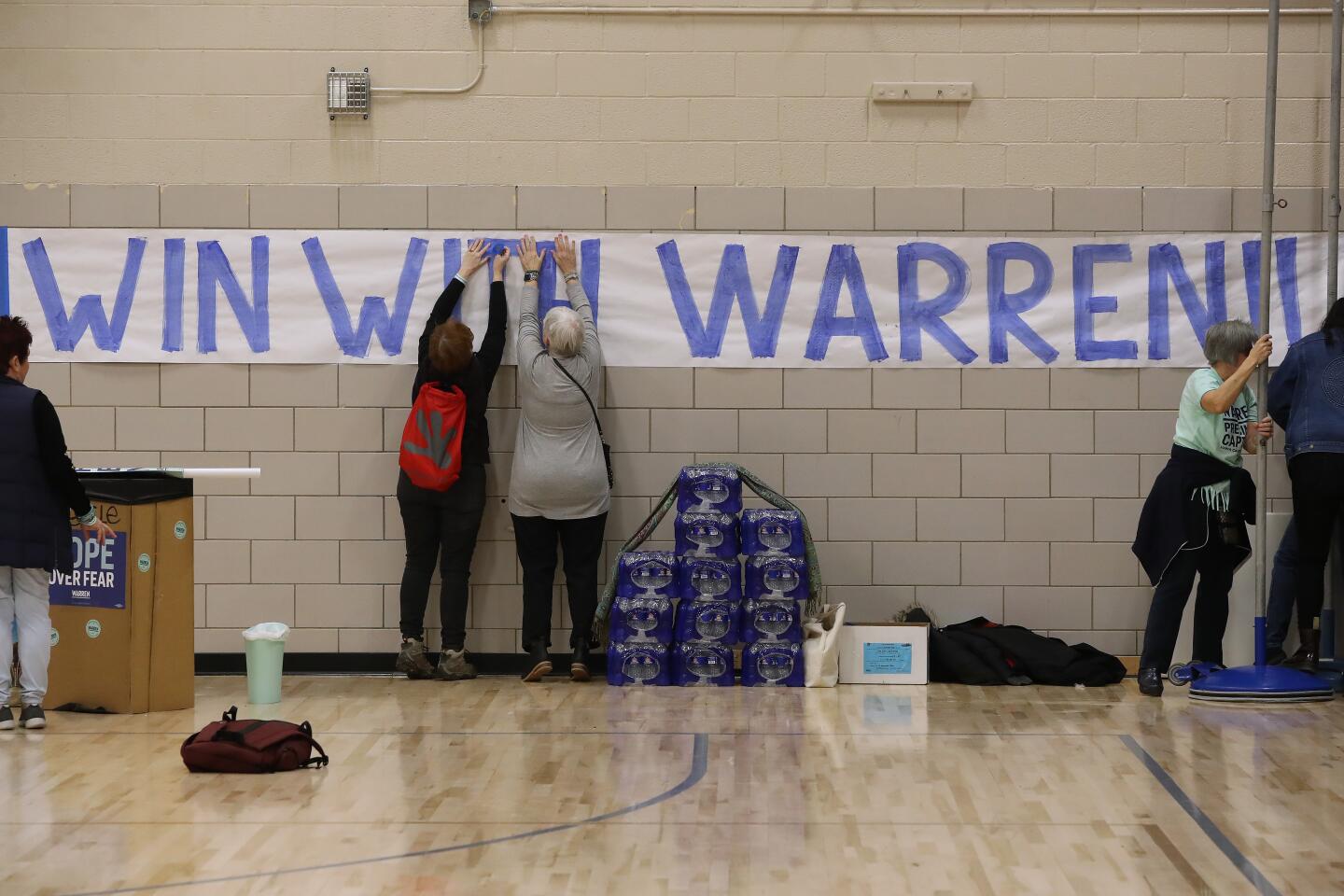

CLIVE, Iowa — They packed into gymnasiums, theaters, even dining halls — some ready to press a case and others still making their minds up through the moment they walked in the door. They girded to hunker down for the evening and stood ready to help settle one of the most dynamic fights for the Democratic presidential nomination in recent memory.

After exhaustively listening to candidates and their campaigns talk at them, text them and flood their homes with dinner-hour phone calls for more than a year, Iowans finally would get to have their say Monday night. The nation was eager to hear them.

At more than more than 1,600 caucus sites in places as diverse as remote rural outposts, bustling college towns, and industrial and meatpacking centers, voters came ready to talk, prepared to be nudged by neighbors and aware that the nature of caucusing meant they might wind up having thrown their support behind someone other than their first choice.

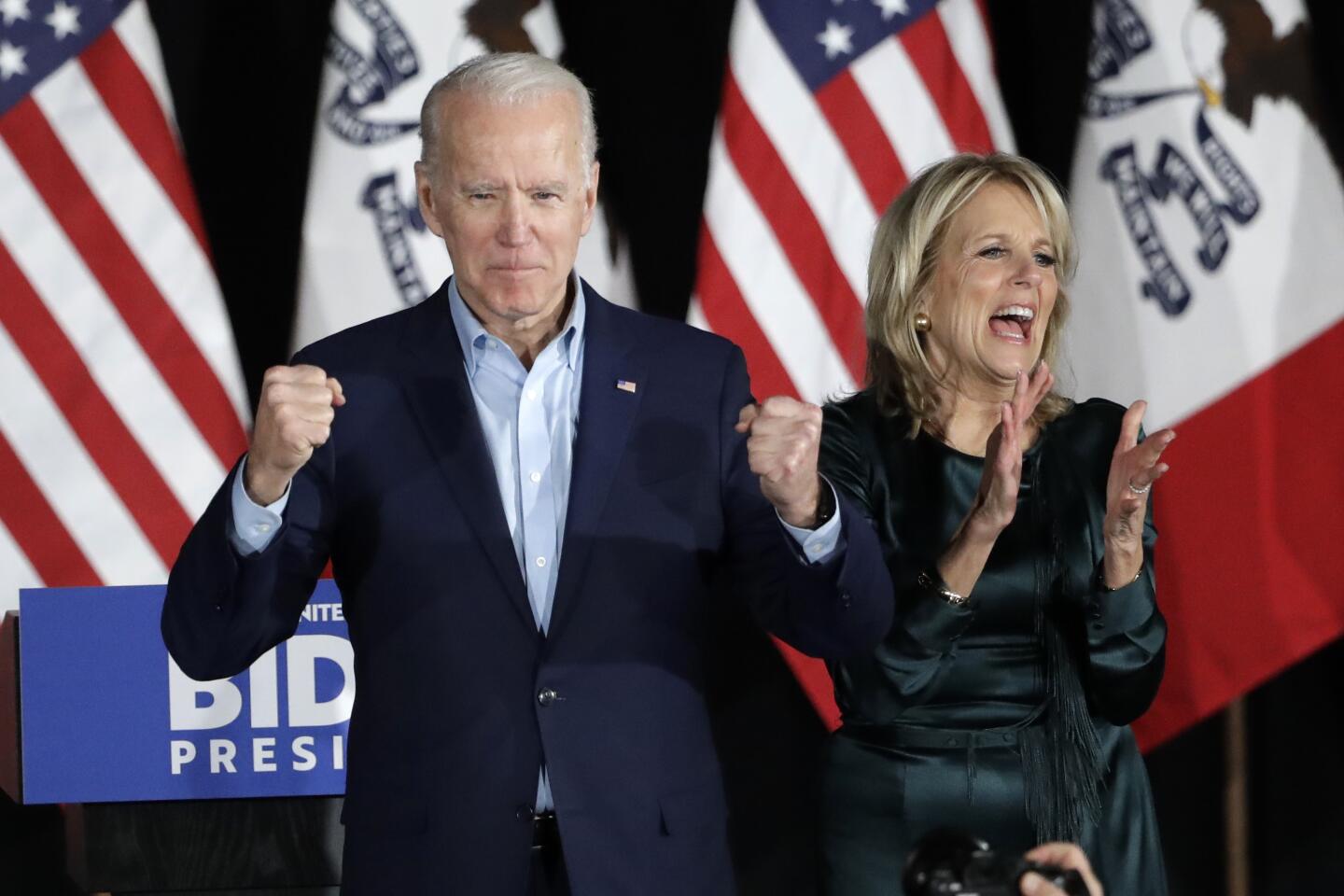

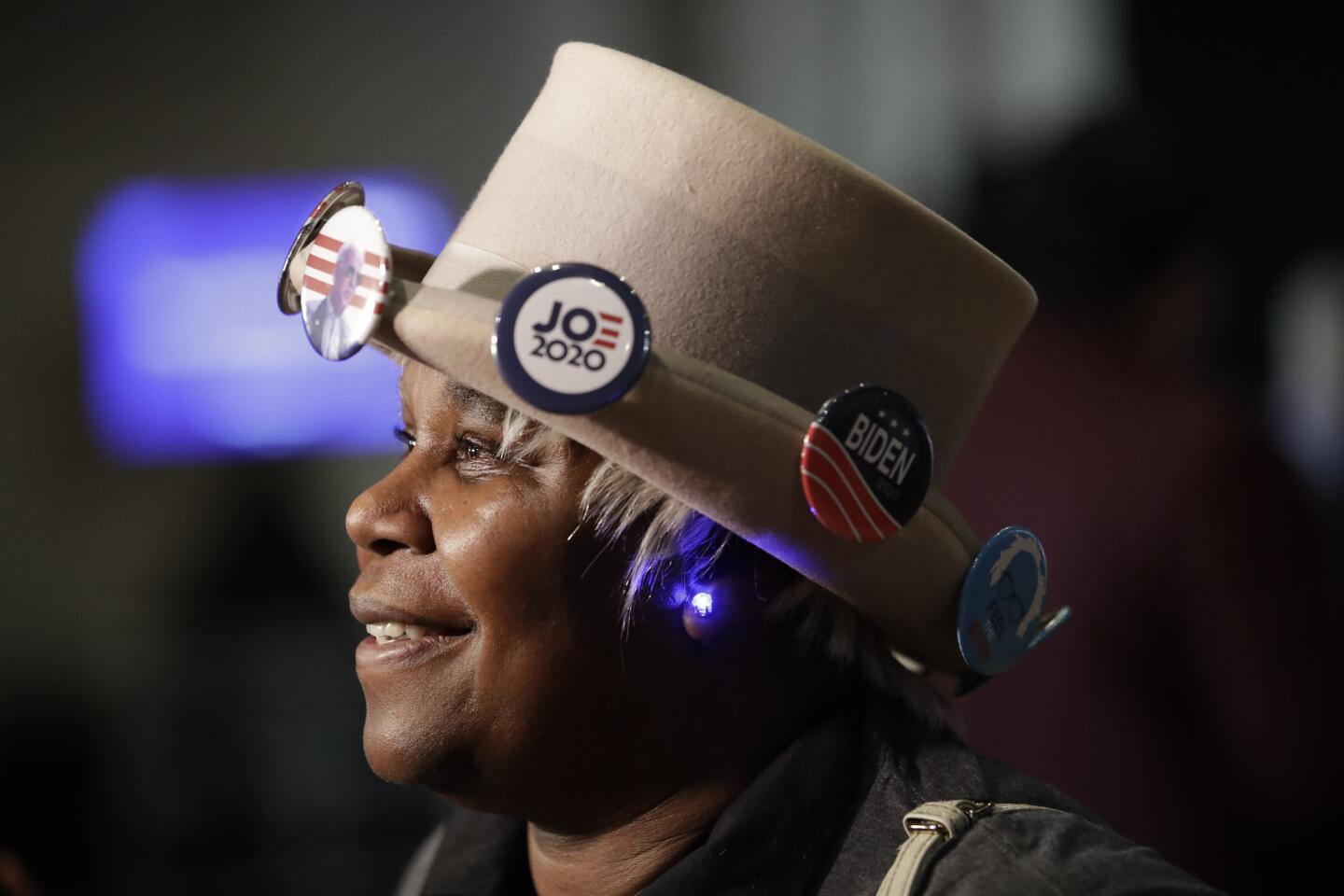

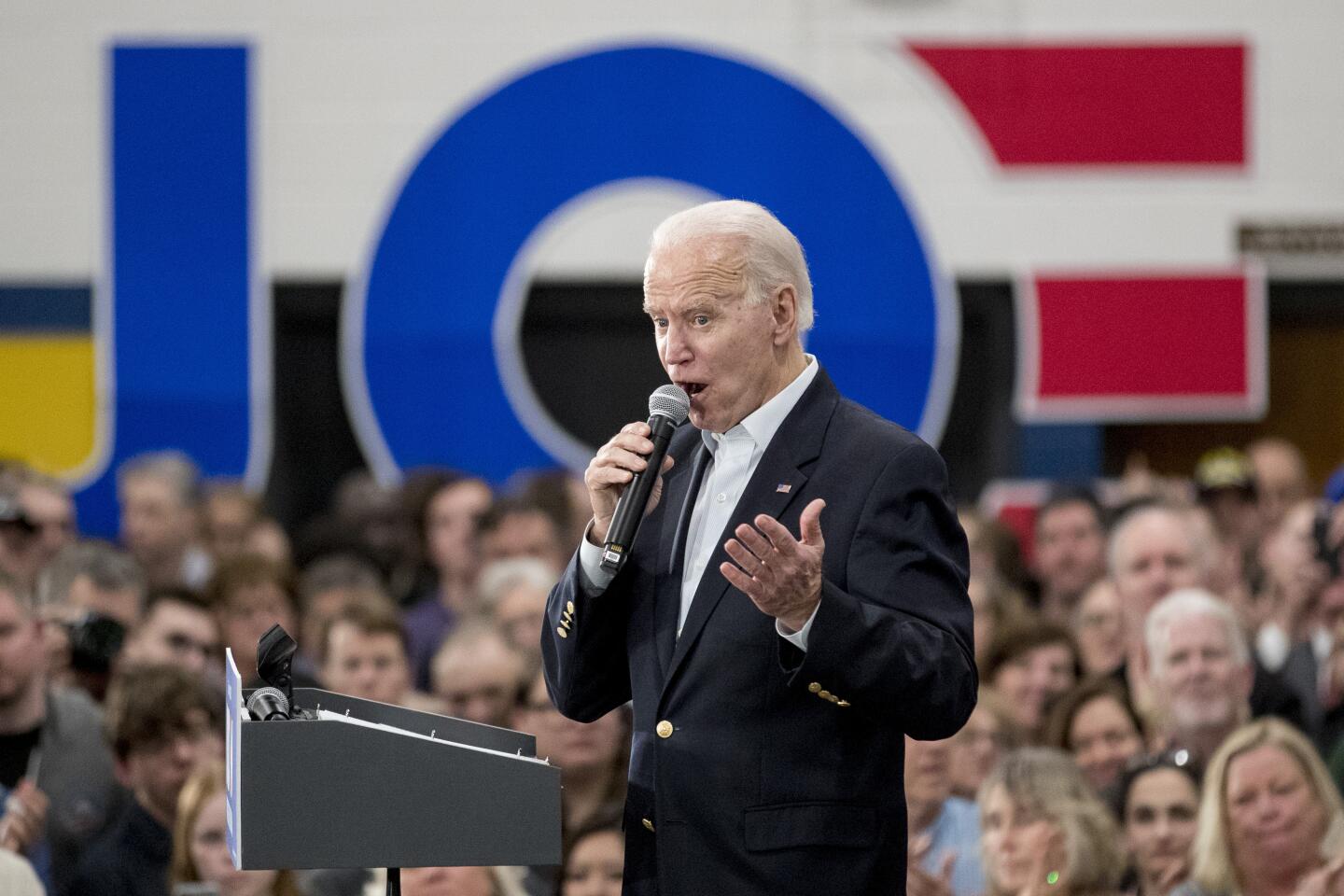

“It just gives me an opportunity as an elderly person to be part of this whole process,” said Ruthanne Free, 90, who came down to the caucus room set up in the dining hall at Walnut Ridge Senior Living in Clive to support former Vice President Joe Biden. Free had never caucused before.

Presidential candidates often urge Iowa caucusgoers to stand in their corner on election night. But a more apt request at Walnut Ridge would be to sit at their table.

The caucus site was specifically geared toward residents at this senior housing complex, along with their families and members of the staff. The accommodations at the converted dining hall included more seating and a relatively low-volume vibe — perfect for caucusgoers like Free, who find standing for hours on end to be a daunting prospect.

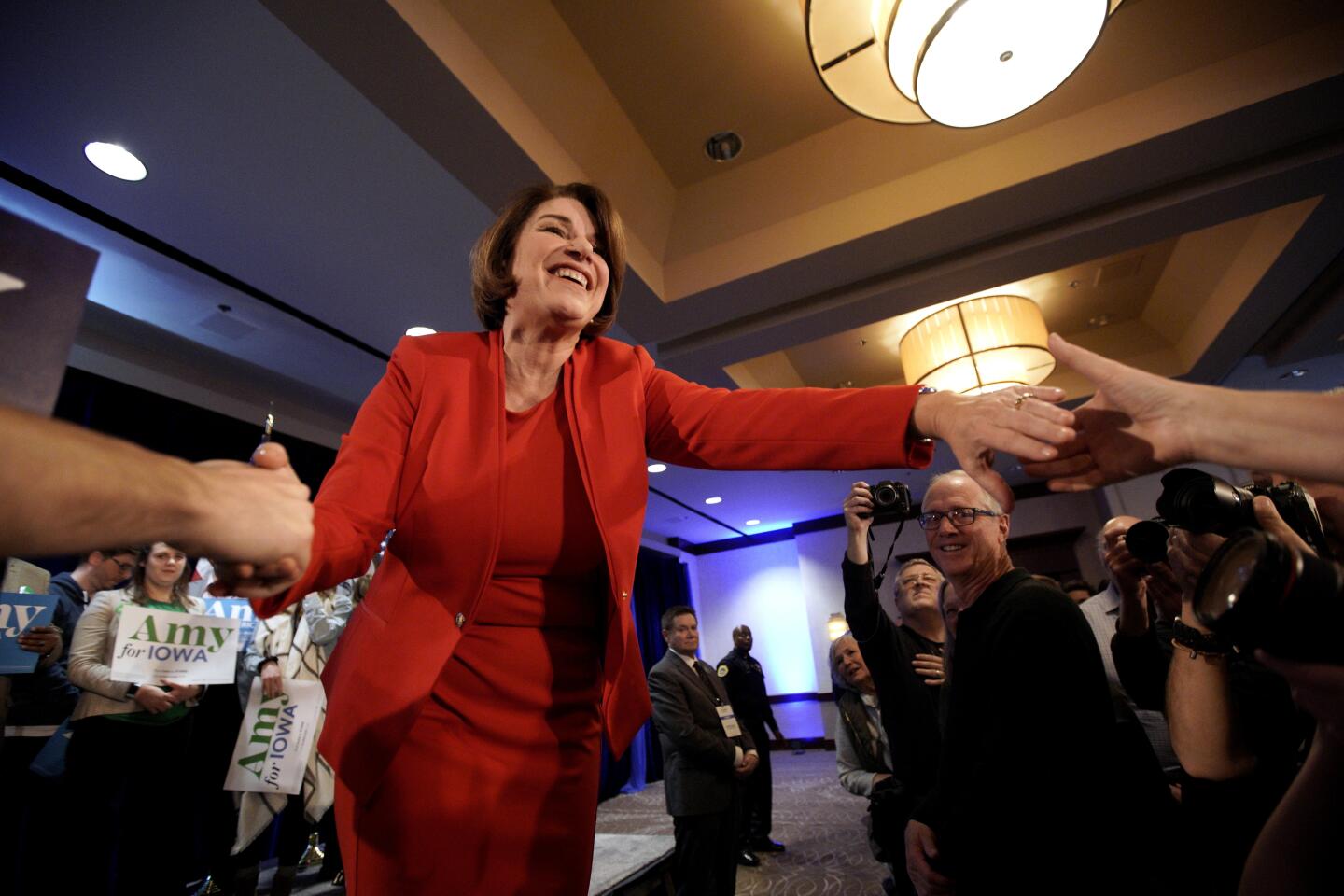

Even before the caucus began, it was clear which candidates would perform well at this location, which hosted about 50 people. The clusters for Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and Biden required extra tables.

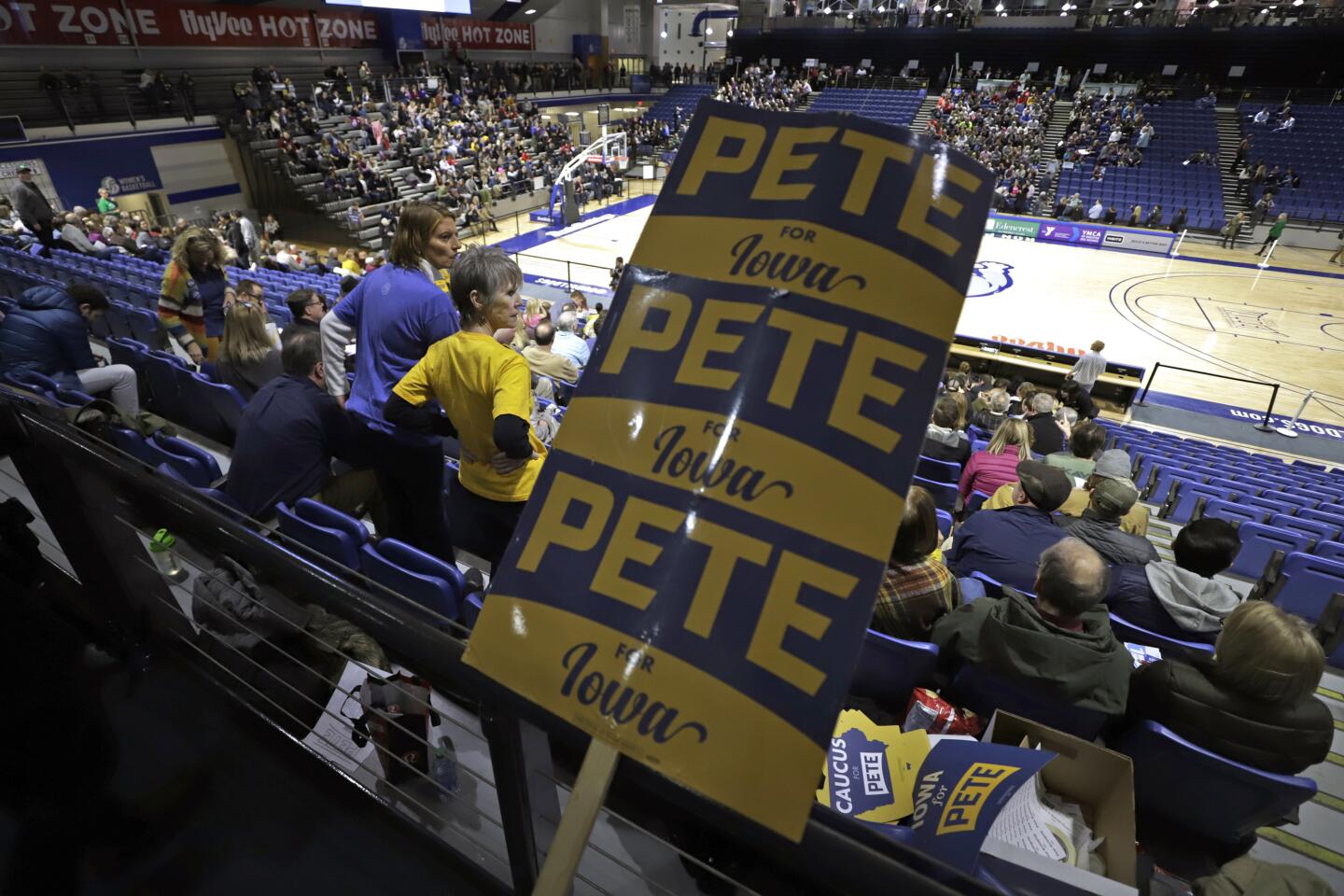

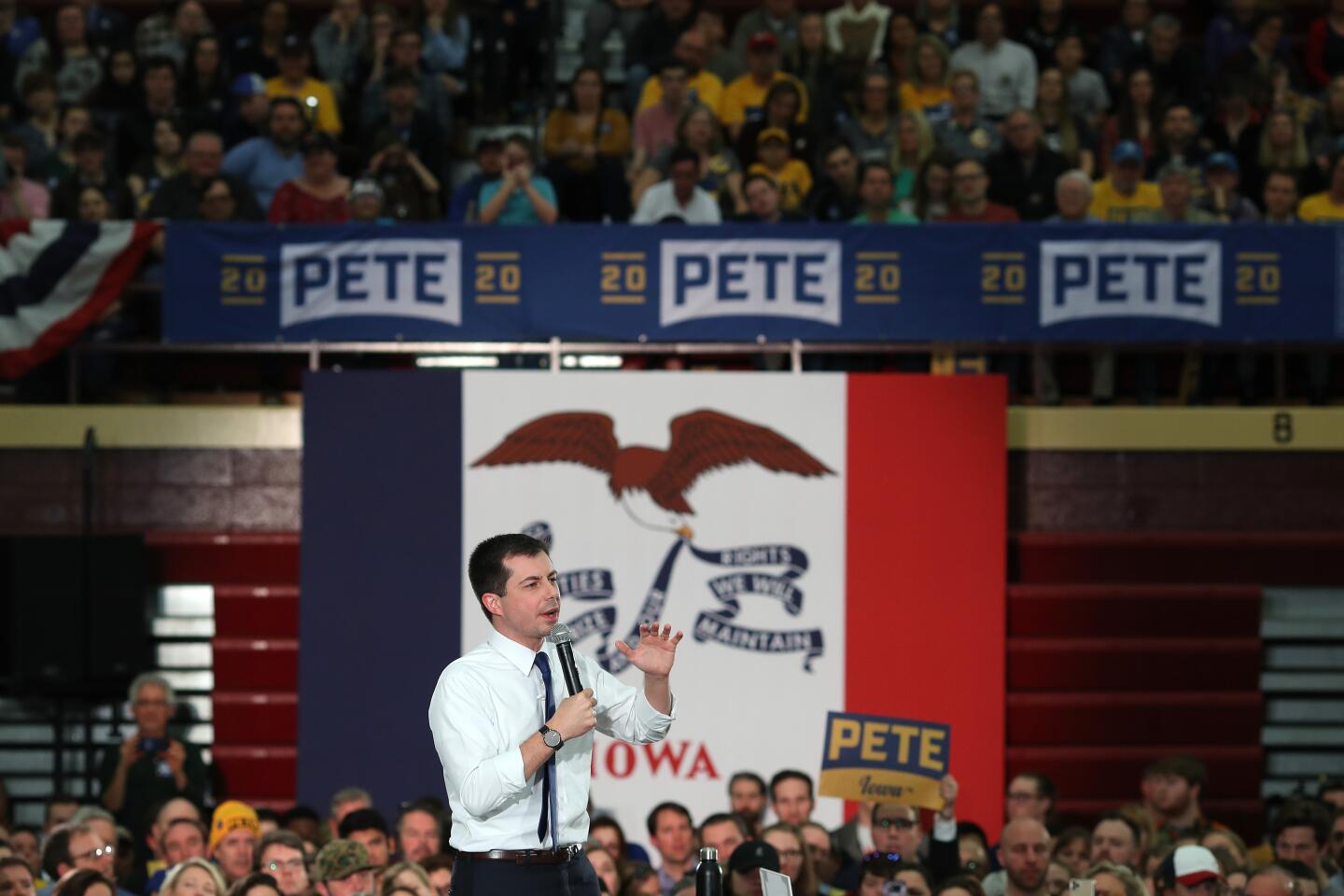

Karen Cameron and her daughter Abby Vens sat at the more sparsely populated Pete Buttigieg table, while Cameron’s parents, residents of the facility, sat with the Biden group.

“I thought it would be less hectic,” said Cameron, a 61-year-old nurse, explaining why she chose to caucus at this site.

When a caucus site organizer came by to ask who at the Buttigieg table would be responsible for keeping track of the count of supporters, she immediately pointed to her daughter.

“What?” said Vens, a 23-year-old teacher. “I don’t know enough!”

Things were more hectic over in Iowa City.

A couple of dozen caucusgoers were lined up even before the doors opened and the marquee lights went on at the Englert Theatre precinct site in this college town two hours east of Des Moines.

In the frantic push to get stragglers on their side, members of the “Yang Gang” wrote “Caucus for Andrew Yang” in pink chalk on the sidewalk by the theater and around downtown.

Across town, hundreds of people filed into the entrances of the University of Iowa’s sprawling student union building, another caucus site. The line was so long that it stretched out a side door.

Outside one entrance, Lauren Willson, 18, a chemical engineering major, greeted voters with a “Students for Pete” sign.

“I love his message of unity and how practical his ideas are,” Willson said of Buttigieg.

In Iowa, 31 counties supported Barack Obama twice before backing Donald Trump in the last election. Voters in such counties are being watched closely at a time when Democrats are obsessed with how to find a nominee who can win them back.

In one such area, Jasper County, just east of Des Moines, a few dozen voters caucused at the meeting room alongside the bar of a modest golf course in the town of Newton.

One caucusgoer gravitated toward Biden, whom she described as a far-from-perfect candidate, but one she considered much more electable than the others. Another suggested she had it all wrong, saying that Trump appealed to voters because he was willing to blow up the status quo and that the Democrats need a nominee capable of doing the same.

Things got underway in the golf course bar as surrogates for candidates made their pitches.

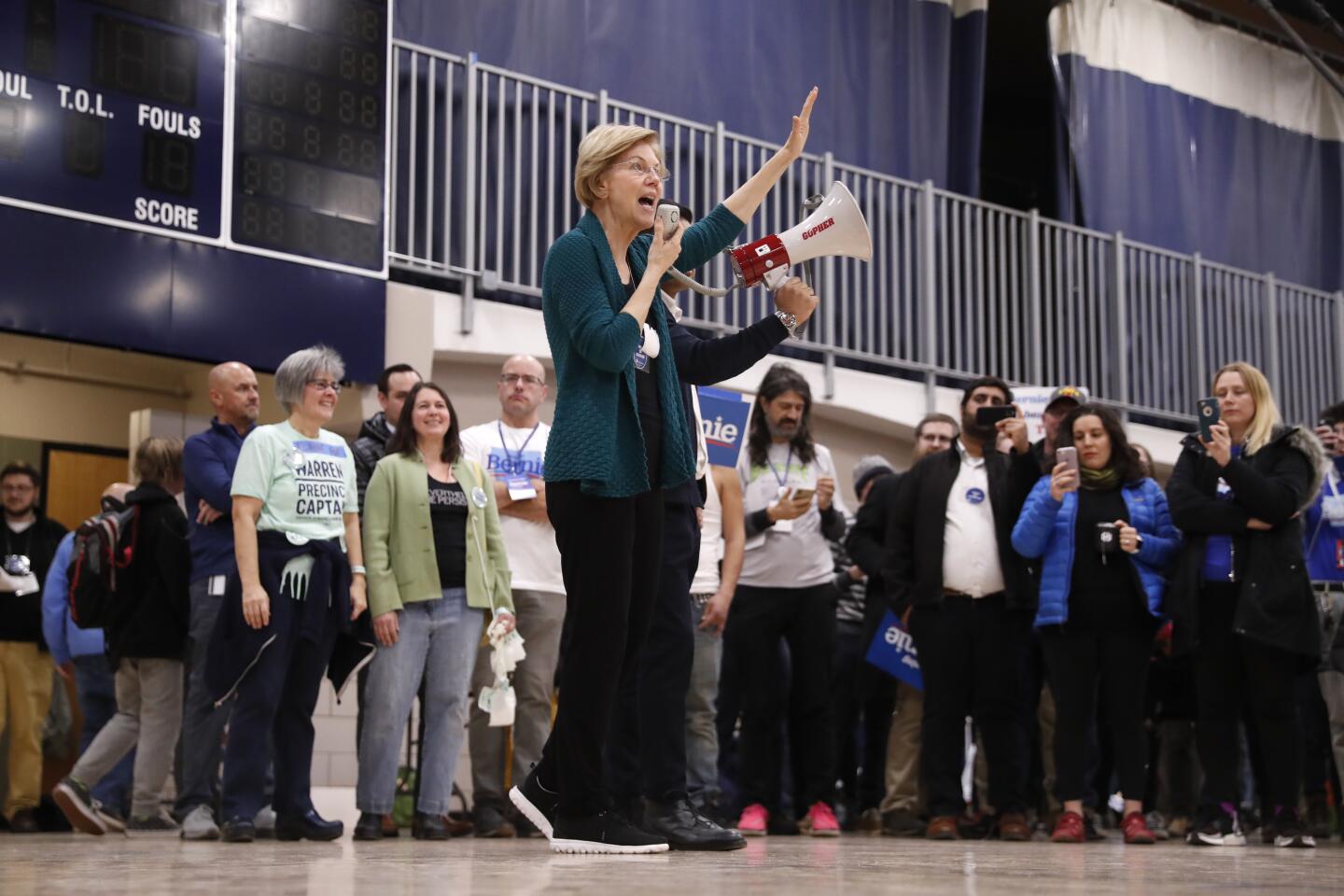

Klobuchar surrogate Daniel Song failed to mind the two-minute time limit. Biden’s representative, George Simpson, forgot his talking points. And Gary Thompson, who was there as Elizabeth Warren’s precinct captain, called Biden and Bernie Sanders too old to be president, and then went on to say that as the father of a gay son, he believed America was too homophobic to elect Buttigieg.

As the caucusgoers prepared to go to their corners for first alignment, they took a short pause so that 9-year-old Mia Van Zante could tell a few jokes over the microphone.

“What do you call a bee having a bad hair day? ... A frisbee.”

With that, caucusgoers started milling around. Sanders’ precinct captain, realizing she had no supporters, implored Yang’s backers. “Can we meet in the middle? Their policies are really similar.”

Not one member of the Yang Gang bit. Ultimately, Buttigieg got two local delegates, and Biden, Warren and Yang got one each.

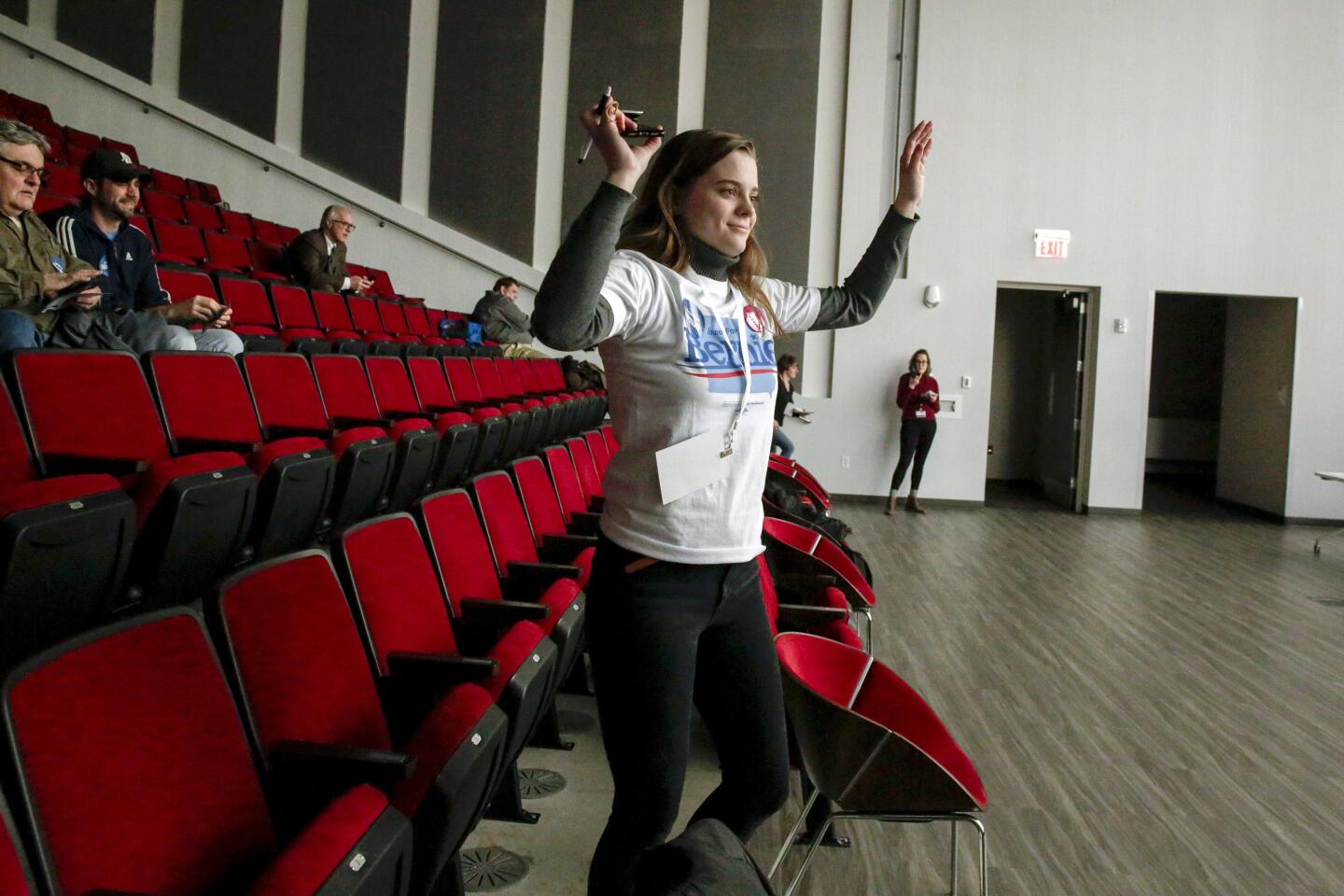

In Waukee, west of Des Moines, caucusgoers filed into a gym, many of them congregating in front of signs posted along the walls: Biden. Buttigieg. Klobuchar. Sanders. Warren. Yang.

But a smaller group of the Waukee Precinct 1 caucusgoers sat down on a small row of chairs in front of a sign that said “uncommitted.”

Uncommitted. Even after all this time. Even on the night of the caucus.

It would be the job of their fellow caucusgoers to woo them to their candidate.

“I just don’t feel like there’s anybody who’s pulling in front for me,” said uncommitted caucusgoer Kelli Hansen, 37, an officer manager at a radio station. “I’m a little bit nervous about who can actually beat Trump. I’m just not ready, with so many candidates right now, to commit to one.”

Back in Walnut Ridge, the seniors were ruthlessly efficient.

In just 30 minutes, some 50 caucusgoers had settled on their preferences and wrapped for the night. Klobuchar won three delegates, while Biden took two and Buttigieg one.

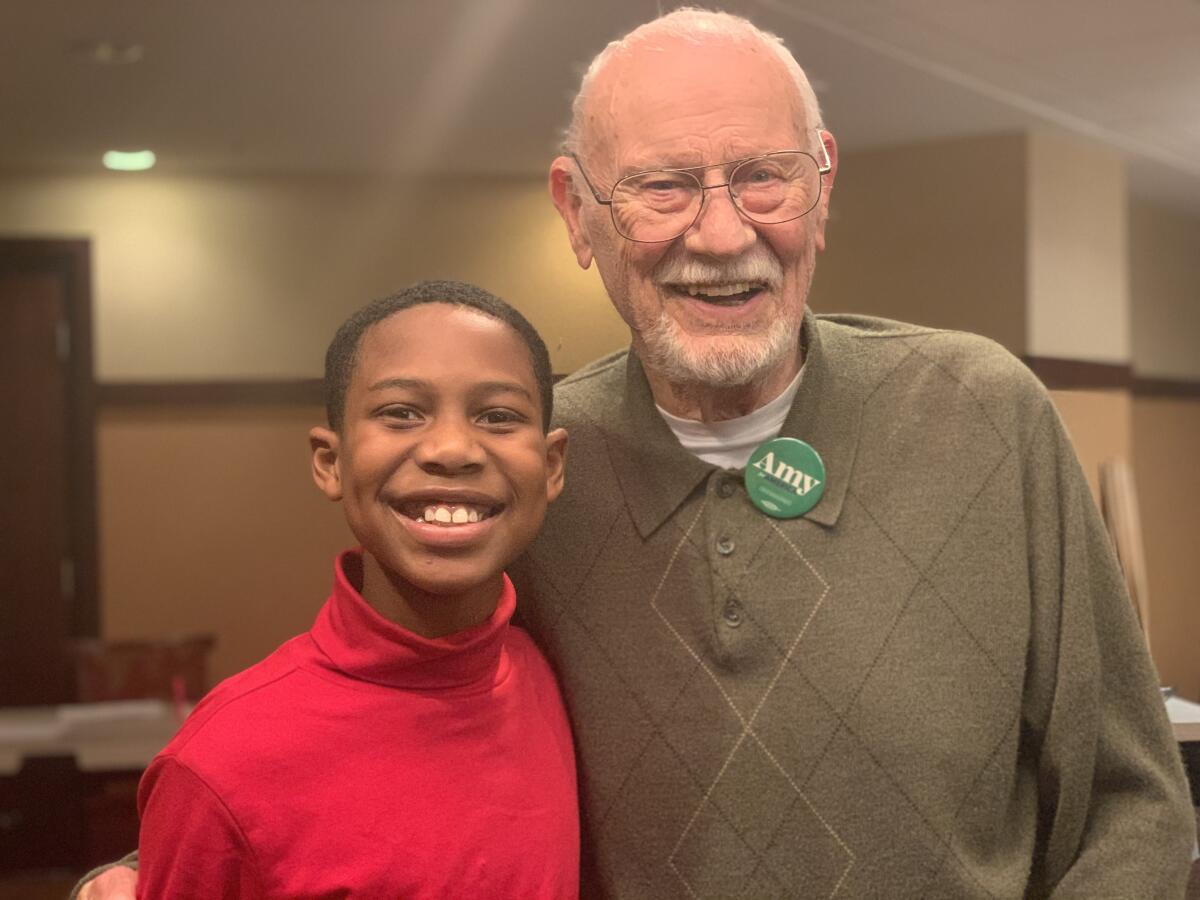

Gene Cutler, 93, personally escorted four Warren and Sanders supporters over to the Klobuchar table, linking his arm with theirs and swaying them with offers of hot dogs.

“You’ve got to sweet-talk them, or break their kneecaps,” said Cutler, who helped organize the caucus.

Kenneth Briggs, 77, was one of the Warren supporters whom Cutler put the squeeze on.

“I let him think he did,” Briggs specified.

Briggs, a minister at a United Church of Christ congregation in Truro, was not surprised that Warren came up short.

“I knew this community was more connected to Amy — one of her representatives came here,” Briggs said. “Some folks in this age group think Warren is a little bit aggressive.”

Beason reported from Iowa City, Mason from Clive and Mehta from Newton. Staff writers Matt Pearce in Waukee and Evan Halper in Manchester, N.H., contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.