Democratic rivals exchange insults in debate, boosting Bernie Sanders’ prospects

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The unusually tense, argumentative and personal tone of Wednesday night’s Democratic debate — clearly the most contentious of the campaign — reflected the urgency of the political moment: Most of the candidates on the stage could be out of the race in less than two weeks.

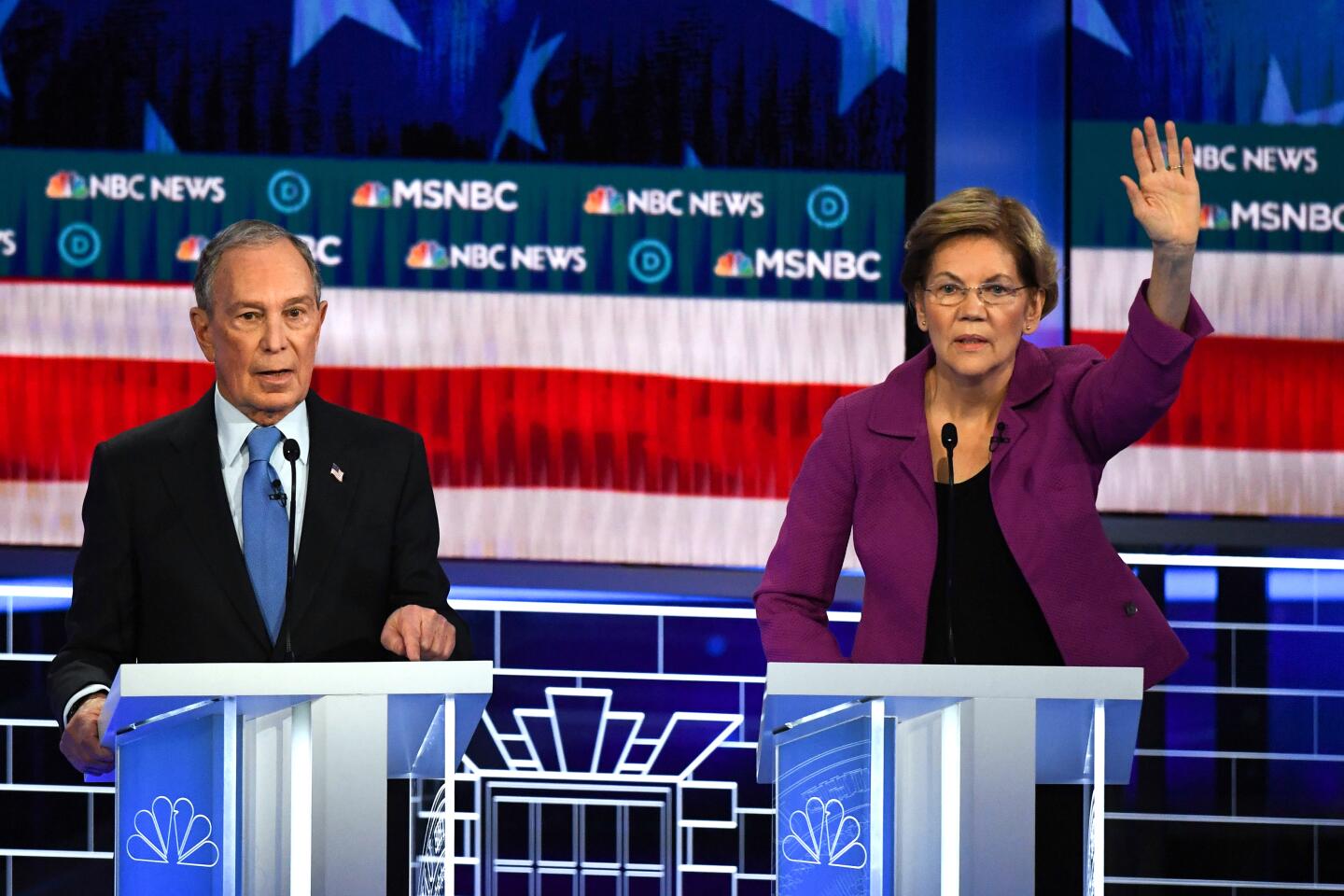

In past debates, when one candidate was perceived as a front-runner, he or she became the target of attacks and scrutiny. As expected Wednesday, former New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg took a lot of the heat. But with so many political crosscurrents buffeting the other five candidates, the attacks flew in all directions, less like a fire hose pointed at one candidate and more like an oscillating sprinkler.

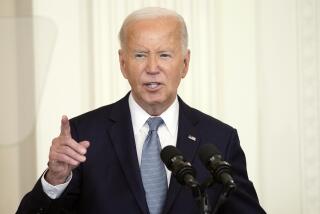

The multiple exchanges — Sen. Amy Klobuchar against former Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Sen. Elizabeth Warren against former Vice President Joe Biden, Biden against Sen. Bernie Sanders, Sanders against Buttigieg, and so on — created a free-for-all that actually looked like a debate. Or maybe a prize fight, as Klobuchar said at one point.

The cacophony had one clear result, however. Like most of what has happened in the last two months, it bolstered the prospects of Sanders, the Vermont senator who is the current front-runner. The debate was a two-hour crystallization of the inability of any of his rivals to emerge as a single, clear alternative.

Sanders leads his rivals in polls by a growing margin and is likely to soon be leading in the delegate count as well. Other candidates are jockeying to be the principal alternative, but splitting the vote.

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg made his debut on a presidential debate stage -- and spent the night fending off bitter attacks from other Democrats as the race enters a critical phase.

In earlier election cycles, a candidate could catch fire later in the process and still emerge the winner. In 1992, for example, Bill Clinton won only one of the first dozen contests before beginning a run of victories that gave him the nomination.

But the party’s heavily front-loaded schedule this year has greatly changed the dynamics. By March 3, when California and 13 other states hold their nominating contests, roughly 40% of the delegates to the summer’s nominating convention will have been chosen.

Bloomberg, who has bet his entire campaign on those March 3 primaries, rode into Wednesday’s debate on an unprecedented wave of advertising funded by his vast personal wealth. He hoped to portray the race as already a two-man fight between himself and Sanders.

Buttigieg, who had strong showings in the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary, expressed the anxiety of the candidates who are at risk of being left behind if that happens.

“We could wake up two weeks from today, the day after Super Tuesday, and the only candidates left standing will be Bernie Sanders and Mike Bloomberg, the two most polarizing figures on this stage,” he said. “And most Americans don’t see where they fit if they’ve got to choose between a socialist who thinks that capitalism is the root of all evil and a billionaire who thinks that money ought to be the root of all power.”

Bloomberg’s weak performance in the debate probably will abate talk of a two-person race, but it will increase the likelihood of Sanders’ continuing to gain strength. The New Yorker’s cool demeanor may have appealed to some voters put off by the shouting and cross-talk. Many more, however, were likely reminded of how much his past positions differ from the mainstream of party.

Bull’s eye on Bloomberg and Sanders, a fiery Warren, and Klobuchar and Buttigieg get personal

If he was weakened, that would continue the political dynamic that has helped make Sanders the front-runner and the rest of the field a muddle.

Each of the candidates who has sought to be an alternative to Sanders has had a moment in the sun, but they have repeatedly eclipsed one another. Because of that, they each arrived at the debate facing a conflicting set of political needs.

Buttigieg and Klobuchar, for example, have both risen in the last few weeks. The former South Bend mayor finished in first place in the Iowa caucuses, which catapulted him to prominence. Klobuchar became the “it” candidate after her surprising third-place finish in New Hampshire earlier this month.

But the two compete for the same political and demographic slice of the electorate — centrist, white, college-educated voters. That, along with a visible personal dislike, put them on a collision course and generated a series of nasty, personal exchanges that kept Klobuchar from having another breakout debate of the sort that propelled her forward in New Hampshire.

At various points, Buttigieg derided her for not being able in a recent television interview to name the president of Mexico, attacked her voting record and rebuffed her charge that he was too inexperienced to be president.

“You don’t have to be in Washington to matter,” Buttigieg said.

Klobuchar said he was misrepresenting his record, and accused him of “trying to say I’m dumb.” She dripped disdain when she said, “I wish everyone was as perfect as you, Pete.”

Biden, long considered the field’s front-runner, came to the debate in deep trouble after humbling losses in Iowa and New Hampshire. His supporters think that if he is to have a chance to revive his campaign, he needs to finish at least second in Nevada’s caucuses and win in South Carolina — states he has touted as his strength because of their diverse populations.

Abandoning his past tendency to remain above the fray, he showed more passion as he took a rare swing at Sanders — on his immigration record — in his closing remarks, which he usually uses to summarize his broad return-to-normalcy themes. He also joined the others in piling onto Bloomberg.

Warren’s goal was to revive her once high-flying campaign after months of sagging polls and a particularly lackluster debate and showing in New Hampshire.

She pursued that in an aggressive display that had her dominating large parts of the debate. In doing so, she ditched the call for party unity that she stressed in New Hampshire and swept a machine-gun-spray of criticism across the field — with one giant exception.

“Amy and Joe’s hearts are in the right place, but we can’t be so eager to be liked by Mitch McConnell that we forget how to fight the Republicans,” she said, alluding to the claims by Klobuchar and Biden that they are able to work across the aisle. “Mayor Buttigieg has been taking money from big donors and changing his positions ... so it makes it unclear what it is he stands for other than his own ambition.”

Comparing Bloomberg to President Trump, she said, “Democrats take a huge risk if we just substitute one arrogant billionaire for another.”

The one candidate she did not pursue in a concerted way was Sanders, her most direct rival for progressive votes. Without a weakened Sanders, it is unclear that even her much stronger performance opens a path for her to return to the top tier.

Sanders’ growing dominance was summed up when debate moderator Chuck Todd, in one of the last questions, asked each candidate what should happen at the Democratic convention if one candidate has a clear lead in delegates, but no one has a majority.

Sanders, clearly anticipating that he will have that lead, said the candidate with the most delegates should be nominated. The other five all disagreed.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.