Older black voters have a 2020 dream: Huge turnout, new president

- Share via

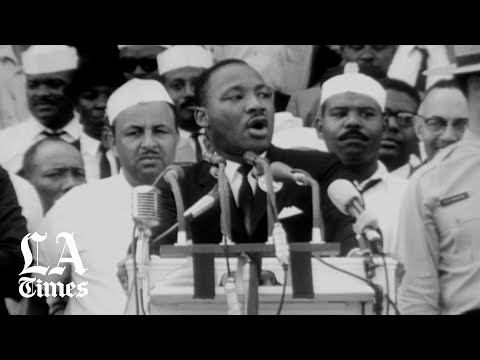

When Alester Pryor thinks about what’s at stake in the 2020 presidential election, her mind drifts to the March on Washington in 1963 and the sight of her mother wiping away tears of pride and pain as they waited for Martin Luther King Jr. to give his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Phyllis Washington Gosa’s mind goes back to her childhood home near Selma, Ala., where she watched her parents practice reciting the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution so they’d be ready for the random civics exams given to blacks to keep them from registering to vote.

Cecil J. Williams recalls a white South Carolina state trooper ripping the film from his camera in the early 1960s when he was a photographer eager to show the world the inequality and bigotry of the Jim Crow South — and twice being jailed because of his work.

Pryor, Gosa and Williams say older black Democrats like them have no illusions about what their country is capable of — or what it needs from its next president.

Cecil J. Williams, a freelance photographer, documented Jim Crow segregation and civil rights demonstrations in his home state of South Carolina.

All three came of age with racism’s daily indignities, but also the promise of the civil rights movement. And they’ve watched as voters replaced the country’s first black president with a man who went on to claim there were “fine people” among the white nationalists at a deadly protest in Charlottesville, Va., — and who early Friday responded to the unrest in Minneapolis over the death of a black man, George Floyd, after a white police officer knelt on his neck, by tweeting “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

Their country’s wild political swings sometimes leave their heads spinning.

“‘One nation, under God, with liberty and justice for all’ — that’s the America we wanted,” Pryor, now 72, remembers thinking in 1963 as King spelled out his vision of a society in which blacks and whites treated each other with mutual understanding and respect.

“But under this current leadership,” she says, “it feels like we’re being set back.”

Pryor, a retiree living in Horry County, S.C, wants voters to draw inspiration from African American history — and to make history in their own right by turning out in huge numbers in the November election and handing President Trump a crushing defeat.

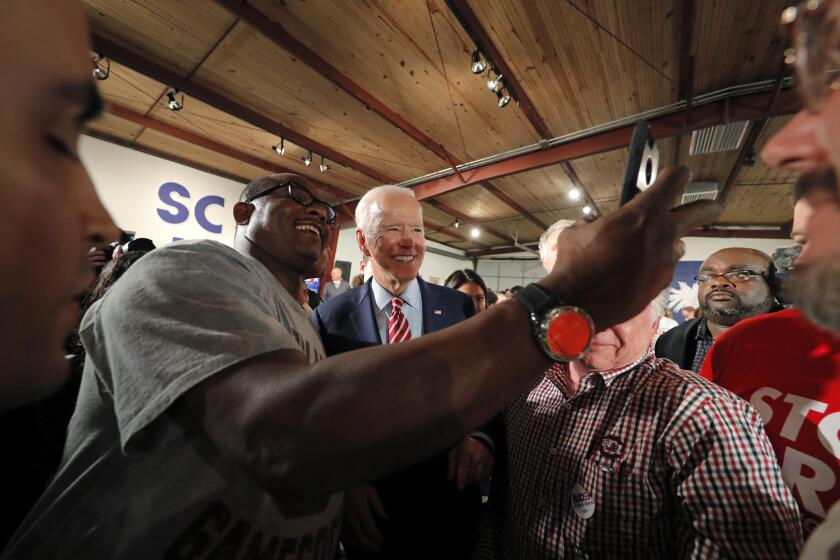

Joe Biden already enjoys a considerable lead over Trump among black voters. A nationwide Suffolk University/USA Today poll taken in late April showed 63% of African Americans saying they’d vote for Biden in the general election, compared with 8% who said they’d back Trump.

But as Biden tries to win over some skeptical younger voters of color, he’s saddled by his own history of miscues.

This month, he caused an uproar after telling New York radio show host Charlamagne tha God that African American voters who have trouble deciding between him and Trump “ain’t black.” Biden quickly apologized, saying he’d been too “cavalier.”

The remark gave the Trump campaign fresh fodder for its effort to chip away at Biden’s lead among black voters — just enough to deny him a victory.

What are black voters in South Carolina thinking as the former vice president has lost momentum in Democrats’ nominating contest?

Pryor, Gosa and Williams all say Trump’s racism makes supporting him out of the question. Gosa says the coronavirus outbreak, which has killed blacks at greater rates than whites in the South and in major cities such as Detroit, Chicago and Los Angeles, has only hardened her opposition to a president she blames for failing to end racial disparities in areas like access to healthcare.

As for Biden’s remark? “I don’t think it was a big deal,” Pryor says. “We have to get past being distracted by things like that.”

The former vice president may not be perfect, these voters say, but Biden would bring stability to a country on edge. Just as important, they say, he’d also safeguard the legacy of the man he served under, President Obama.

“Every time I post something on social media,” Pryor says, “I tell people to remember Nov. 3, 2020 — and vote! It’s an honor to be able to cast a ballot.”

Alester Pryor remembers the exact spot where she sat on the ground with her mother at the foot of the Washington Monument — a teenage black girl from Kansas about to watch one of the most stirring speeches in American history.

‘People died to get us that right’

Pryor recounts the events of Aug. 28, 1963, as if they happened yesterday. She remembers the exact spot where she sat on the ground with her mother at the foot of the Washington Monument — a teenage black girl from Kansas about to watch one of the most stirring speeches in American history.

But what stuck in her mind was the crowd forming around her.

Among the marchers filing past were blacks from Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and other states in the Deep South where racial segregation was the rule and where voting rights were still a fantasy for African Americans.

One young man walked by on crutches, and word spread through the crowd that he’d been injured by police during a civil rights demonstration down South.

“You see,” Pryor’s mother told her, “these are the people who were on the front lines, the people who’ve lost friends and neighbors, who’ve been attacked and had dogs turned on them.”

Pryor says that when she registered to vote for the first time ahead of the 1968 presidential election, her parents celebrated by taking her out to dinner in Kansas City, Mo., near where they lived. They did the same when her sister registered.

“My mother and father made sure we voted in every election, because people died to get us that right,” she says.

Pryor now lives near the Atlantic resort of Myrtle Beach, S.C., along a stretch of coastal farmland where enslaved Africans once labored on cotton and rice plantations.

She says she’s still dreaming of the day when those words in the Pledge of Allegiance, especially the “justice for all” part, will fully apply to Southern blacks, and African Americans in general.

Her big fear is that Trump and the GOP will try to prevent African Americans from voting in large numbers in November, using existing legal hurdles such as voter ID laws or by blocking the widespread use of mail-in ballots in Democratic-leaning states like California.

She has this message for any African American voter considering sitting out the election: “Your vote matters. If it didn’t, they wouldn’t try to suppress it.”

‘We evened out the playing field’

Williams, 83, also worries that the gains of the civil rights movement are being eroded and forgotten.

As a young freelance photographer for the African American magazine Jet, he was arrested and briefly imprisoned — once in 1960 and again in 1961 — while covering civil-rights marches and boycotts in South Carolina.

“Those of us who had to battle to make that right available, we evened out the playing field so African Americans could vote today,” he says with frustration as he looks back on the picket lines, marches and boycotts he covered. “We’re standing on the shoulders of all the people who marched and fought and died to make that happen.”

The debate over reparations for slavery is getting new attention through the 2020 presidential race. For the descendants of slaves in South Carolina, it’s personal.

In a famous photo taken of Williams at a gas station in 1956, he appears to stare into the viewer’s eyes while drinking from a “white only” water fountain. The act of defiance, during a trip to document his state’s segregated beaches, could’ve gotten him arrested or beaten.

That history weighs on him every election season — and especially this one, because he fears that younger Americans don’t share his sense of urgency about voting.

Now Williams teaches visitors about the often-dangerous work and achievements of African Americans in South Carolina at the nonprofit civil rights museum he designed, built and runs in Orangeburg.

“If you don’t have an appreciation for the past and where you came from,” he says, “then it’s difficult to navigate the future.”

‘The courage to stand up’

Gosa grew up poor in rural Tallapoosa County, Ala., about 90 miles east of Selma, her home now — and the site of the infamous “Bloody Sunday.”

In 1965, white officers beat and tear-gassed black voting-rights demonstrators as they tried to cross the city’s Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Gosa didn’t attend the march, but her voice turns bitter when she recounts how her parents repeatedly tried to register to vote in the late 1950s and early ‘60s, only to be denied again and again because they were black.

“We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity ...”

As a little girl, Gosa learned civics by watching her parents memorize the Preamble of the Constitution and say the words back to each other in their farmhouse — hoping their knowledge would one day make a difference but fearing that it might be futile.

Even successfully answering surprise quiz questions didn’t guarantee success when black Southerners tried to register to vote.

Gosa recalls also having to order food at the back door of a restaurant with nowhere to sit and eat it, and drinking from “colored” water fountains. And she thinks back on all the times she rode in the car with her parents past nearby Auburn University, which she thought of as “the school for white kids” because it was off-limits to black students.

“The hope was, if they could get the right to vote, they could elect people who were fair and who would not treat them like their parents and grandparents were treated,” Gosa says of African Americans who dreamed of equality then.

That faith in the transformative power of the vote, she says, “that’s what gave my parents — as well as the people who marched on the Edmund Pettus Bridge — the courage to stand up and make the United States live up to the idea that every man is created equal.”

Times can change — and people can change their times.

Gosa, a retired pharmacist, became the first black woman to graduate from Auburn’s integrated pharmacy program in 1976.

With every advancement for black people, she says with a sigh, come setbacks.

Gosa bristles over the slights and arbitrary rules that African Americans were forced to accept as the cost of being black in America when she was young, and that burden them today.

The fatal shooting of a 25-year-old black man named Ahmaud Arbery in neighboring Georgia — confronted by a white father and son who were initially allowed to go free after telling police they suspected him in a burglary — triggers an ache in Gosa that’s been passed down through the generations.

In her own backyard in rural Alabama, Gosa says the farmland in Tallapoosa County that her family has owned since her enslaved ancestors were set free is contaminated from all of the landfills that the state allows to be situated in poor, black areas.

Gosa says African Americans in the South can’t make progress on present-day injustices without the full force of the federal government to back them up — or elected leaders who identify with their hardships.

“Only God knows what things are going to be like moving forward,” Gosa says. “So we must have a president with some sense — and who understands the Constitution.”

‘We will persevere.’

— Alester Pryor

In 2009, 45 years after attending the March on Washington, Pryor was overcome with emotion as she stood in almost that same spot on the Mall, this time to hear Barack Obama take the oath of office at the U.S. Capitol.

The U.S. economy was in a death spiral then, too, and a multicultural coalition of voters had placed the fate of the country in his hands.

“The land of the free, the home of the brave,” Pryor thought to herself as she pondered the capacity of a nation that had once sanctioned slavery to make a black man president.

America’s in need of that kind of galvanizing moment in November, Pryor says of the new era of conflict, uncertainty and upheaval besetting the country.

“We will persevere, and we will, once again, become the greatest country in the world,” she says. “No matter what comes, this is still a country we can be proud of.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.