‘You are a Black man at all times.’ 3 generations tell of their family’s hopes and fears in the Trump era

- Share via

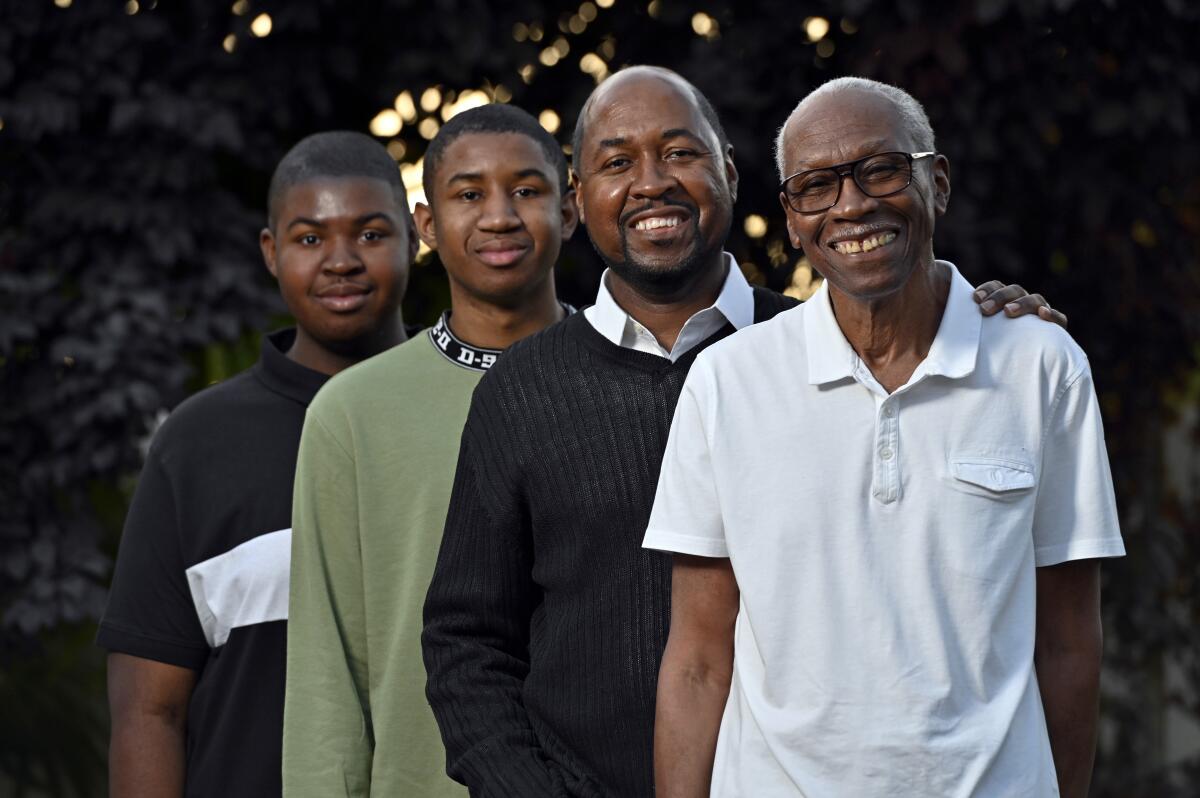

LAS VEGAS — Curtis Shelton grew up in the 1950s at a time when Black people couldn’t live or work where they wanted, or gamble in this city’s famous casinos. His son Allen remembers living in public housing as a little boy; he went on to become a successful real estate agent, raising his family in a gated community in the suburbs. Curtis’ grandsons, Allen Jr. and Christian, are college students coming into their own in the Trump era.

All of these men exude a determination to do better than the generations that came before them — the same thing every American strives for. But their shared optimism competes with an uneasiness that also runs through the Shelton family.

Even though these three generations of men are separated by more than half a century, they all struggle with the pressure of being Black men in a country that fails again and again to respect people who look like them.

“They say what goes around comes around — we’re still protesting,” Curtis, 76, said one day while standing outside the house he’s lived in since the family left public housing.

“Until there’s a great change across the board,” he said, turning to Allen, “his grandsons are going to be protesting. Because we’ll never get our just due.”

For the Shelton men, Tuesday’s presidential election isn’t just about choosing a leader. It’s about their yearning for physical safety, their desire to live out their lives without the burden of bigotry. It’s about how they — like many other Black people — consider this election tantamount to a moment of truth, a way to give meaning to phrases about justice and equality in the Constitution by voting out a racist president.

Alice’s Garden, a community farm in Milwaukee’s historically Black neighborhood, gives residents peace, quiet and a place to connect with their own roots.

With much of this year focused on race, Allen and his wife, Wendy, opened up their home for a conversation about the discomfort they feel over the dangers that Black men face in America. Black men may be proud of their identity, they say, but many carry inside them a mix of rage, fear and hope that’s so messy — and sometimes so maddening — that they shy away from revealing how their skin color weighs on them.

Police killings of Black men, armed or unarmed. A president who called peaceful anti-racism protesters thugs and anarchists, and football players “sons of bitches” for taking a knee. Curtis, Allen, Allen Jr. and Christian are coping with this time of racial upheaval and protest in different ways.

Curtis, who lives on his own, said he doesn’t have it in him to join demonstrations against biased policing and racial violence, but not because he disagrees with the cause. He’s just not sure he could handle the rage it would bring to the surface that’s rooted in tragedy he’s endured because of racism.

Allen, 56, shares something his late mother used to tell him when he was growing up that he’s tried to impart to his own children: “When you leave this house, know who you are.”

But Allen Jr., 21, and Christian, 19, look uncomfortable talking about the dangers that come with their Blackness. They strain to reconcile the good things their parents have taught them to believe about themselves with what America tells them they are.

“I don’t think I truly understood what it meant to be a Black man in America until I saw all of this outpouring of support for us,” Allen Jr. confesses as he thinks of millions of protesters marching for George Floyd.

“I felt more and more like that could be me,” he said of Floyd, who died after a police officer knelt on his neck for more than eight minutes.

The Sheltons raised their sons to be resilient Black men by drumming into them another lesson from their own parents: Nothing can hold you back, even though you’re Black.

“It was so entrenched in our mind it was kind of like a handed-down heirloom,” Allen Sr. said.

But their teachings to their sons about perseverance, the loving words about being precious in God’s eyes — they no longer feel like it is enough.

“It became apparent that we had to tell them, ‘You need to be aware that you are a Black man at all times,’” said Wendy, 53. “In hindsight, I question whether we should’ve started telling them that when they were 4 or 5 years old, because of the way that the world is now.”

Allen and Wendy settled in a suburban community of two-story homes 20 minutes north of the anything-goes atmosphere and distractions of the city. From the time their sons were young boys, they stressed the importance of education.

Allen Jr. is an engineering major at Santa Clara University in Silicon Valley. He recently had a paper on image-recognition technology for visually impaired people published at a global humanitarian conference. Christian is a performance art major at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, studying opera.

This is the first year Allen Jr. and Christian are eligible to vote in a presidential election. To stress the importance of Black people voting, their parents turned it into an outing, taking their sons to a drive-in event called “Drop It Like It’s Hot” that had a live DJ. They all chose Democrat Joe Biden and his running mate, California Sen. Kamala Harris, for president and vice president.

When asked how they felt about Trump, Allen Jr. and Christian just shook their heads in dismay.

For black voters who lived through segregation, this election is the new front line for fairness

Curtis voted several days later, making this the first time that all three generations of his family have participated in a presidential election. He said he was was proud of his grandsons.

“I don’t care who they voted for as long as they did,” the lifelong Democrat said. “All the people who died to get the right to vote, and [people] don’t vote? What’s up with that?”

Allen and Wendy said lately they’d been afraid to take walks around their neighborhood for fear of being harassed or physically attacked because of their skin color. This anxiety churns in Allen, but “as a Black man,” he said, “you try to hold back, hold it in.”

Trump’s and Biden’s reactions to racial injustice and protests illuminate how they approached the issue of race throughout their political careers.

Allen Jr. and Christian looked on. They’re both soft-spoken.

Like his older brother, Christian is still working out his feelings about violence against Black men, but he gave words of reassurance to his parents.

“They did a good job of teaching us,” Christian said, turning toward Wendy. “I feel like I can shoot for the stars.”

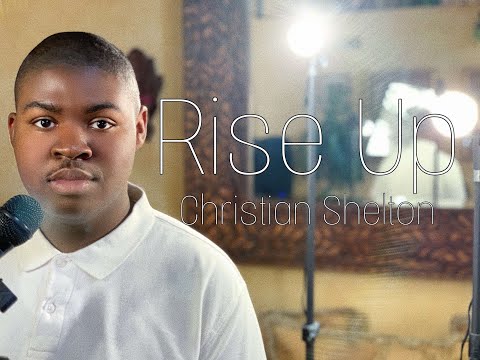

Christian is a talented vocalist who caught the attention of the artist Lizzo. She posted a split-screen of her swooning over him singing a Corinne Bailey Rae song. Local Democrats invited Christian to sing the national anthem at a voter registration event featuring Harris.

The young men listened as their parents recounted racist incidents. The sons had heard the stories before and they’re unsettled by them every time.

There was the time vandals spray-painted a Nazi swastika and “KKK” on two banners advertising Allen’s real estate business. And the time when a traffic cop mistook the couple for other people, pulled them over, accused them of having a gun and handcuffed them.

“They had us in the middle of a major street in December, in the cold, on our knees with our backs to them,” Wendy recalled. She remembers “hearing guns clicking.”

“That stuff has just been pushed down for years and years,” Wendy said. “But this year, I just felt compelled to tell some of the stories — to say how I feel as the mom of these two Black boys.”

Voters in the battleground state of Wisconsin are using street art, church services and vigils for Black people killed by police to call not only for justice but also for Americans to restore their faith in one another.

Allen’s emotions have crept up on him too in recent months.

In June, angry and grief-stricken over what happened to Floyd, he took a walk in the dark to clear his mind.

“Then bam, bam, bam — it hits you,” Allen said. His eyes welled up with tears, and he was relieved no one could see him.

What would his sons think if they saw the man who told them they were born blessed looking so vulnerable because of his race?

Las Vegas — with its neon lights and penchant for turning vintage buildings into piles of rubble — might not be the first place people think of to learn about America’s history of racism. But the Shelton family is a testament to a time when Black people were unwelcome and invisible in this desert playground.

Most Black people who settled in Las Vegas in the middle of the last century migrated from the segregated South for jobs — at a defense contractor during World War II, a chemical plant near the city, casinos and building dams on the Colorado River.

Once here, they encountered what some coined the “Mississippi of the West.” Black people were banned from the Strip’s casinos and hotels and forced to live five miles north in what’s known today as the historic Westside.

Wendy takes a black-and-white photo off the wall showing her father, Odell Nichols Jr., as a boy dressed in his Sunday best with his family during a dinner in 1955 at the Moulin Rouge, the city’s first integrated casino.

The Westside resort allowed Black people the dignity that the rest of Las Vegas failed to recognize, in a setting with its own glitz and glamour. Sammy Davis Jr. and other Black stars paid visits after dazzling white audiences at the city’s whites-only casinos. Waiters wore white gloves.

Wendy said she grew up around Black men who weren’t intimidated by the constraints imposed by racism, so she wanted to teach her sons to be the same way. Allen Jr. and Christian said they’re proud to have come from such strong people.

The flashiness of Las Vegas suddenly ends when Allen drives under the freeway into his and Wendy’s old neighborhood. The Moulin Rouge is now a gravel lot. There have been plans to entice businesses, but the whole area looks motionless, forgotten.

Allen pulls up to his father’s one-story house on a block of simple homes with tidy lawns, and Curtis comes out eager to talk.

Curtis, a preacher who occasionally gives sermons at the church Allen went to as a child, reflects on the experience of his parents. They migrated from Arkansas and managed to put down roots in Vegas, a getaway that limited Black people to mostly service jobs. Curtis fondly recalls working at the Jockey Club resort on the Strip when he was younger and the white employees who treated him like their equal.

For black voters who lived through segregation, this election is the new front line for fairness

But he believes white people fail to appreciate this about Black people — their desire to be self-reliant.

“Like what James Brown said: ‘Open the door and I’ll get it myself,’” Curtis said. “I don’t want you to hand it to me.”

He used a single word to describe what he sees as the motive for a rise in hate crimes and white supremacist activity since Trump was elected: “Retaliation.” White people are punishing Black people for the advancements they’ve made since his parents’ time, he said.

Curtis is quick with a smile but he carries a lot of pent-up pain inside his slim frame.

In 1986, his son Anthony, Allen’s younger brother, died after being thrown from a car when it was deliberately run off the road by a vehicle driven by a white man, according to the two survivors.

It was a gut-wrenching end to a night of celebration. The boys’ mother, Carolyn Shelton, had organized a big party to celebrate Allen’s graduation from Grambling State University, a historically Black school in Louisiana, and Anthony’s graduation from high school.

The Sheltons were convinced the incident was racially motivated. The Las Vegas Review-Journal reported at the time that police didn’t dispute the account, but they lacked leads.

Anthony’s death sparked in Curtis a resentment of white people.

“That’s why I don’t watch the protests and don’t get into it, because that feeling comes back, and I try to keep that down,” Curtis said of his anger. “With help from God,” he keeps it under control.

Joe Biden’s choice of Kamala Harris, a Howard University alum, is cause for celebration at HBCUs.

During that lonely walk in June, Allen Sr. thought about how he could channel his anger over racial injustices old and new, and about the power of a Black man using his voice as a force for good.

He didn’t let on to his family that he’d shed tears. Instead he turned to Christian.

His son had sung “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” at the state Democratic convention four years ago.

How times had changed.

Allen told Christian that on his walk, he’d listened to a song by Andra Day that was perfect for this new season of protest, and that he should record a version of it. Soon after, Christian did.

Even the song’s title was fitting.

“Rise Up.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.