5 things to watch for in Biden’s meeting with Russia’s Vladimir Putin

- Share via

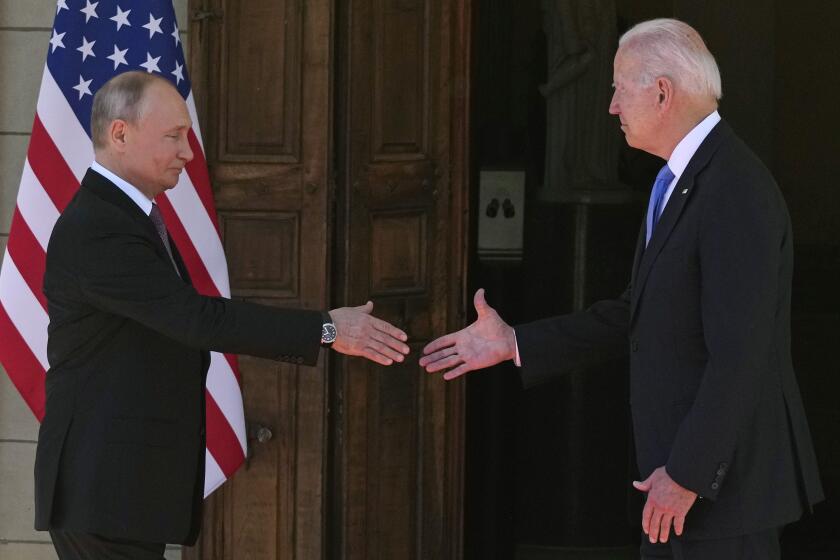

WASHINGTON — President Biden‘s first head-of-state sit-down with his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, on Wednesday promises to be a test of mettle and wills, each leader confident in his ability to hold the upper hand over the other.

Both have been fixtures in global politics for years, but the relationship between their two countries is at possibly its lowest point since the end of the Cold War.

Biden is not planning a “reset” of relations, which his advisors have described as a trap previous U.S. presidents fell into. Few analysts expect concrete agreements to emerge from Wednesday’s summit, but that alone may not be a measure of success or failure.

“We should decide where it’s in our mutual interest, in the interest of the world, to cooperate, and see if we can do that,” Biden said Monday of how he would approach the meeting with Putin. “And the areas where we don’t agree, make it clear what the red lines are.”

Here are five things to watch for from the tete-a-tete at a lakeside chateau in Geneva:

An un-Trump summit

In contrast to former President Trump’s meetings with Putin, Biden is following normal protocol and is accompanied in the closed-door meeting by his secretary of State, Antony J. Blinken, and a translator. Putin has in tow his longtime foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov.

Trump famously refused to allow other officials in the room for some of his talks with the former KGB operative, and confiscated the translator’s notes.

President Biden brings up human rights and cyberattacks in meeting with Putin. The Russian leader later rejects blame and accuses the U.S. of abuses.

Biden also made a point of consulting with NATO allies ahead of the meeting, sharing ideas and positions. Biden’s aides made clear the summit would be all-business and that there would be no joint news conference afterward.

There will be four or five hours of nonstop talks, an administration official said, and “no breaking of bread.”

Human rights

Biden is expected to raise the issue of human rights with Putin, but he will not likely get very far.

The U.S. president carries with him the cases of several American citizens languishing in Russian prisons. And he can cite the jailing of prominent Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny.

The Putin foe, who survived poisoning with a Russian nerve agent last year, was jailed when he returned to Russia after being treated in Germany. His health has reportedly faltered in prison. On Monday, Biden was asked at a news conference after meetings in Brussels what Navalny’s potential death in prison would mean for U.S.-Russian relations.

“Navalny’s death would be another indication that Russia has little or no intention of abiding by basic fundamental human rights. It would be a tragedy,” Biden said. “It would do nothing but hurt his relationships with the rest of the world, in my view, and with me.”

The sentencing of Putin critic Alexei Navalny doesn’t solve the Russian president’s problems.

Cyberattacks and military aggression

At the top of Biden’s list of complaints to raise with Putin are a series of cyberattacks targeting vital U.S. infrastructure, sensitive government agencies and American elections.

Although Putin has denied responsibility, U.S. intelligence is convinced Moscow at the very least sanctioned the damaging intrusions, to which Washington has responded in at least one case with an undisclosed “proportional” counter-breach.

The administration has also imposed economic and diplomatic sanctions on Putin and his associates, but without apparently influencing their behavior.

In recent years, Putin’s Russia has expanded its military presence, establishing a major army base in the Mediterranean for the first time in nearly half a century and reaching into Turkey and parts of the Middle East.

Biden will attempt to establish a “clear laydown” of U.S. national interests that if the Russians challenge them they will be “met with a response,” said an administration official previewing the summit for reporters.

Belarus, Georgia, Ukraine

Putin continues to lust after these three former Soviet republics, but only Belarus remains firmly in his orbit.

The Kremlin continues to lend firm support to Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, a dictator who has detained and tortured thousands of dissidents, according to human rights organizations.

Ukraine and Georgia, meanwhile, yearn to stay free and are seeking protection from, and even membership in, NATO as Putin amasses troops and conducts military operations to threaten them. Russia invaded part of Ukraine in 2014 and continues to occupy the Crimean peninsula.

Arms control

If the two can find an area of common ground, it might be arms control. Both have shown interest in resuming talks that would extend or follow on New START, the last U.S.-Russian arms control treaty.

But the reality is Putin prefers a state of conflict with the West because it distracts his citizenry from domestic problems, elevates his status on the world stage, and arms him for what he sees as a genuine battle — fighting U.S.-led Western liberalism.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.