Between trips upstairs to gather treasured photographs and important documents, Diane Francis stood at her living-room window and stared over the hillside at giant black plumes of smoke.

The view was eerily familiar. Seventeen years earlier, she and her husband stood on the road leading to their property and watched as their house burned down, devouring everything they owned.

“It’s stunning to have the fire in front of you again,” Francis said.

This time, she was lucky. In the triple-digit July heat, gusty winds drove the blaze away from her home. Other Alpine residents just miles away were not: 53 homes were damaged or destroyed in this summer’s West fire.

Whether fire or earthquake, mudslide or drought, natural disaster is an inextricable part of the California experience. And just as it upended Francis’s life, disaster threatens to snarl the next governor’s plans. Emergency response is rarely discussed as a campaign issue, but once in office, a governor’s on-the-ground handling of unexpected catastrophe and its immediate aftermath can define his legacy, for good or bad.

”A governor should expect that his agenda is going to be interrupted at some point by natural or manmade disaster. It’s just going to happen,” said former Gov. Gray Davis, whose faced an unexpected power crisis while in office. “Nobody wants to think about it, but you need to prepare for it.”

How a state’s chief executive responds when calamity strikes often makes it into the history books. The choices a governor makes ahead of disaster are no less consequential — and often present high political risk with little payoff.

“The first principle is that [governors] get rewarded for how they react to crises to a greater degree than whether they act to prevent them,” said Bruce Cain, professor of political science at Stanford University.

The disaster currently occupying headlines — wildfires that have ravaged the state in historic proportions these last two years — has pushed the policy debate over fire prevention to the forefront.

But experts say the next stage of the discussions must confront how we build communities to better withstand fire, a topic that has long been politically fraught. Disaster preparedness is expensive — whether it’s retrofitting buildings and highways to withstand quakes, improving water infrastructure to prevent deadly floods or deciding if development should be allowed in fire-prone areas.

When governors challenge the status quo, “the resistance is enormous” said Cain.

“How do you make the case to voters to do this really, really difficult thing?”

Keeping the lights on

Within his first year as governor, Pete Wilson was flying in a helicopter over the Oakland hills, watching as a firestorm raged against the darkening sky.

“I was looking down on about 3,000 little orange squares — each of them representing a home,” Wilson said in an interview. “It struck me what I was seeing. I was near tears. I just thought, ‘My God, what a tragedy this is.’”

In his two terms as governor, Wilson encountered every strain of California disaster: The 1991 Oakland fires and the 1994 Northridge earthquake were among the most destructive.

He won plaudits after the quake for repairing the I-10 freeway’s collapsed overpasses in less than three months, using his emergency powers to cut red tape and give hefty bonuses to motivate contractors to finish their work early. With earthquake fears fresh in the minds of voters, he followed up with a $2-billion bond to seismically retrofit highways statewide, work that experts said has made state roadways significantly safer.

“Disasters are crisis situations that can make or break political figures,” said Mark Ghilarducci, director of the governor’s Office of Emergency Services. “If you come on too much, you’re tending to get in the way…. But if you’re slow to lead, slow to respond, then it’s problematic. It’s a fine line.”

In his earlier turn as governor, Jerry Brown flubbed the response to the Mediterranean fruit fly infestation that threatened to decimate the state’s crops. Brown found himself caught in a battle between farmers clamoring to spray pesticide to stop the infestation and environmentalists who were fiercely opposed.

During the 13-month saga with one zany episode after another — 1.3 billion sterile flies were released in hopes of zapping the Medfly population by infertility, a state official drank a glass of watered-down pesticide to prove it was safe — Brown came off as indecisive and ultimately decided in July 1981 to spray.

“It was just a PR disaster — and it went on and on,” said Miriam Pawel, author of the new biography “The Browns of California.”

Brown’s handling of crises during his current tenure has showed a more assured leadership style. Not one to show up at the scene of an unfolding emergency, his signature has been frank talks on the danger posed by natural disasters and how climate change will only exacerbate those threats in the future.

He used those crises as opportunities for more sweeping policy changes. The four-year drought gave cause for the state to regulate its groundwater for the first time in California history. The dry spell, along with wildfires, has been cited by Brown to bolster ambitious plans to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

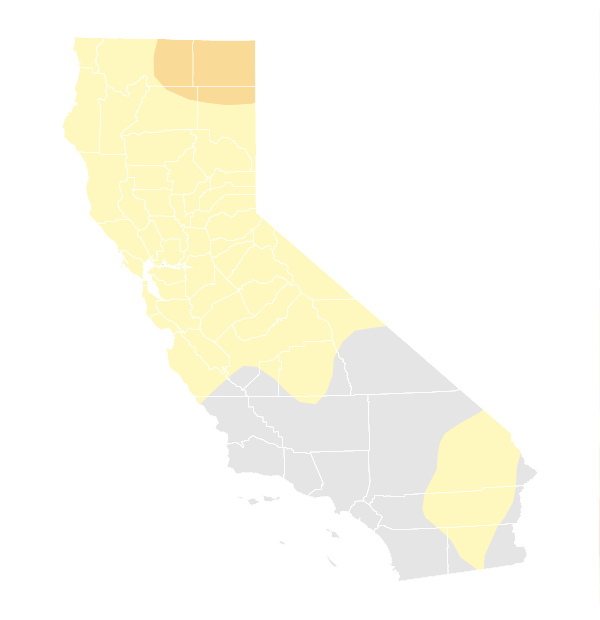

Drought milestones during Gov. Brown’s tenure

Dec. 2011: The drought begins

Jan. 2014: Brown declares a state of emergency

Oct. 2014: California has its driest month of the drought

April 2015: Brown issues mandatory water restrictions

April 2017: Brown declares the drought over

May 2018: Brown makes water restrictions permanent

It’s not just Mother Nature that poses a threat. Unexpected manmade catastrophes can similarly hobble state government.

When Gov. Pat Brown ordered police to remove protesters from Sproul Hall at the UC Berkeley campus during the Free Speech Movement of 1964, the resulting images of students being dragged out of the building prompted a swift backlash.

Ronald Reagan seized on the incident in his successful 1966 campaign against Brown. His pledge to “clean up the mess” at Berkeley was especially resonant, Pawel said.

“It became symbolic that the state is out of control and Pat Brown does not have control,” said Pawel, a sense that had been reinforced by the Watts Riots in 1965.

Davis said he did not get a single question about the state’s energy deregulation during his 1998 run for governor. But when California found itself with electricity shortages in 2000 and 2001, it consumed his administration and ultimately led to his recall in 2003.

“It envelops you. That’s all you’re focusing on — keeping the lights on,” Davis said. “But those are the cards you’re dealt.”

The immediate aftermath of a disaster is a punishing test of one’s ability to lead. But there can also be a silver lining: crisis-sparked momentum that can break through political logjams. Spending money to prevent disaster from occurring, however, gets no such boost.

“Money always seems to be available to clean up a disaster, but much less is available to prepare for it,” Davis said.

California’s largest cities have not endured a major earthquake in the last 20 years. Because of that, the next governor might not find sufficient popular desire to spend more state money on safety retrofits. A physical or cyber attack on the power grid could plunge the state into blackouts, but with scant public focus on that possibility, it’s unclear whether the next governor will make it a priority.

Fire, however, weighs heavily on the minds of most Californians. Over the last year, California has contended with the largest, most destructive wildfires in its history. And the state projects that wildfires, along with other disasters, will be more extreme than previously thought due to climate change.

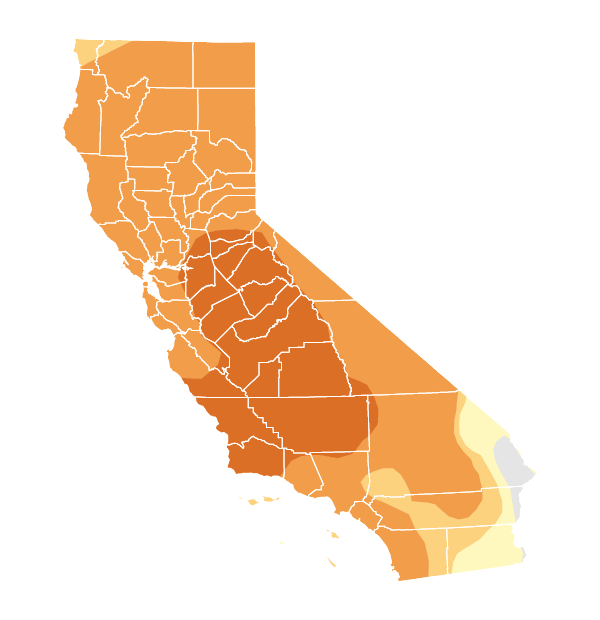

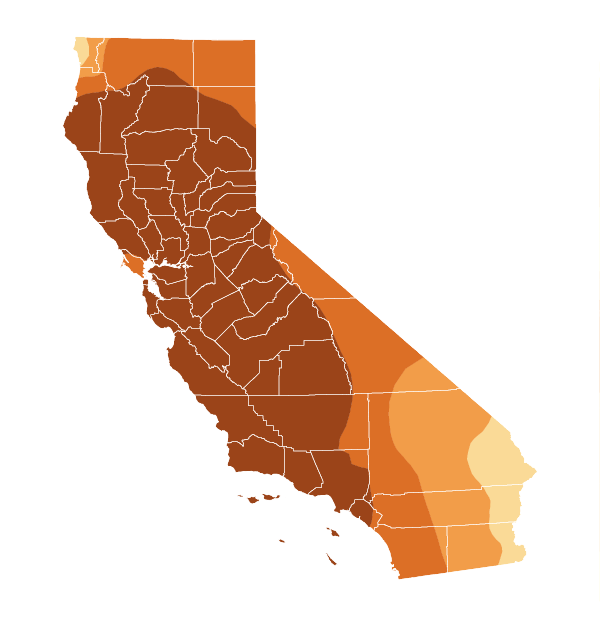

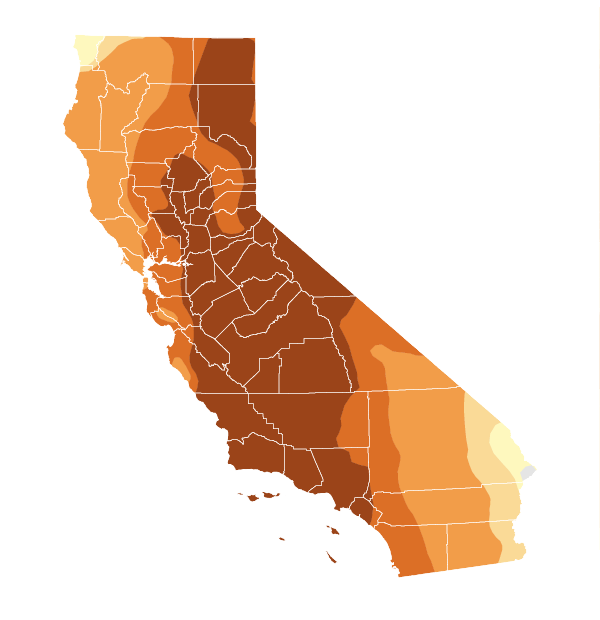

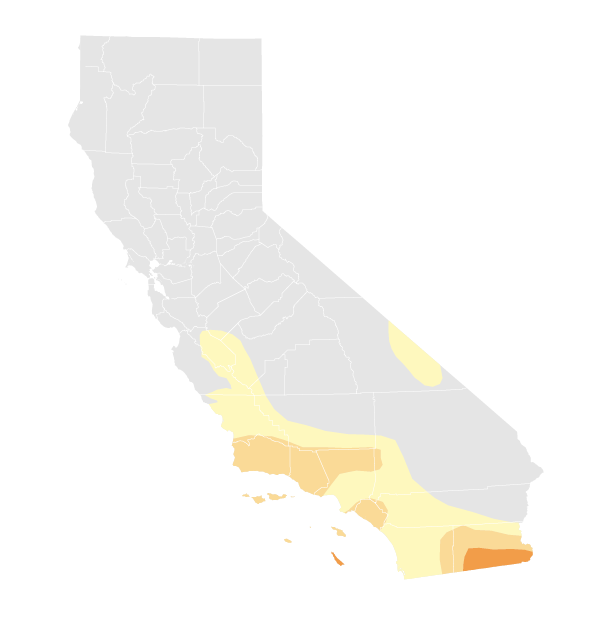

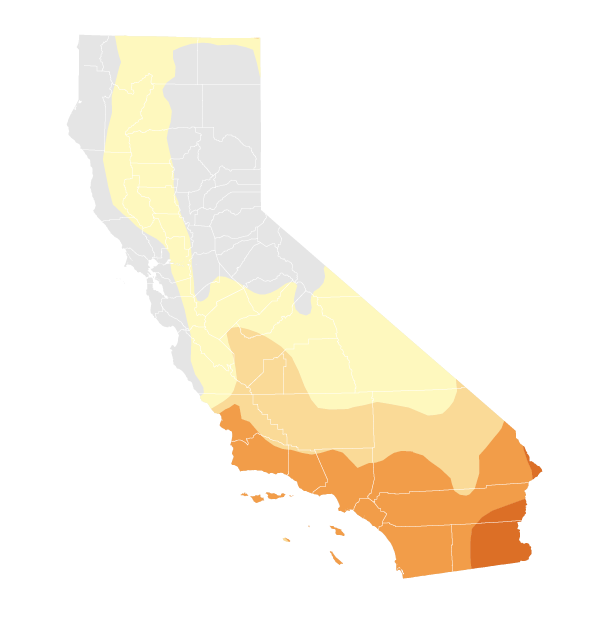

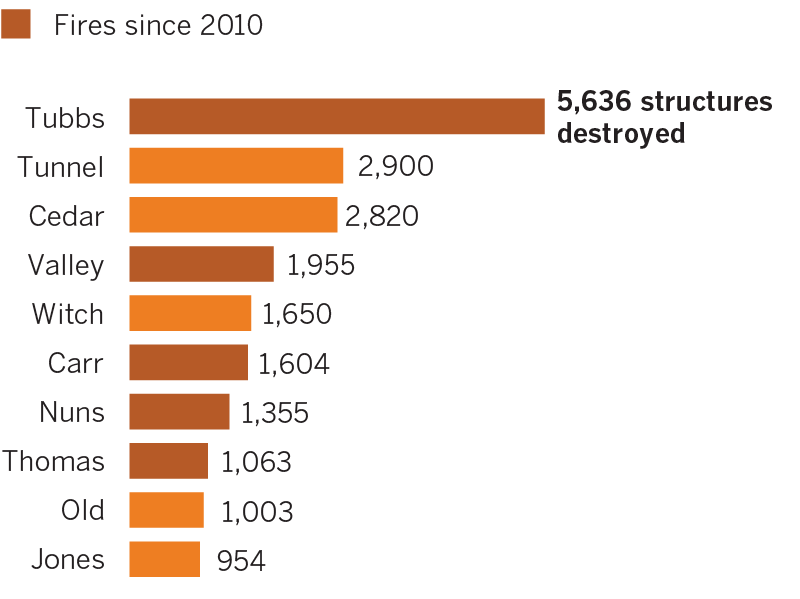

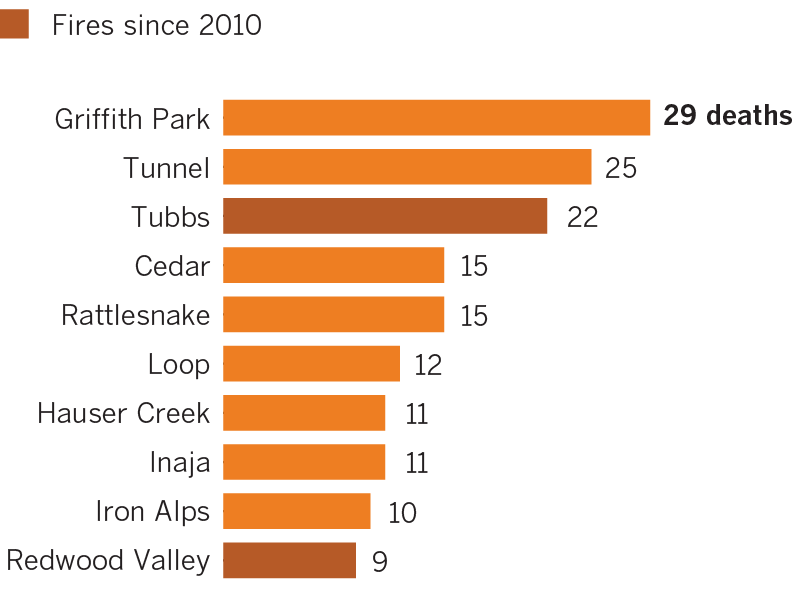

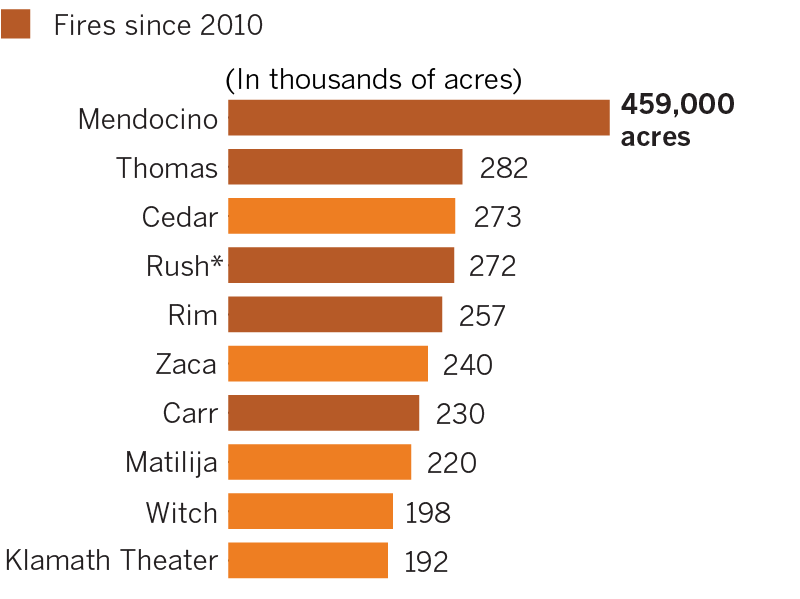

Wildfires burning larger, deadlier in California

Several of the deadliest, most destructive fires in the state’s history have happened in the past decade.

Most destructive wildfires

Deadliest wildfires

Largest wildfires

If the next governor hopes to make progress in protecting the state against wildfire risk, he’ll have to spend political capital on the WUI.

Pronounced woo-ee, like an elongated exclamation, WUI stands for “wildland-urban interface.” Picture a Venn diagram with the state’s nature spaces on one side, and where people live on the other. The area where they overlap — that’s the WUI.

About one-third of California homes are considered to be in the wildland-urban interface. While many have focused on how hotter, drier weather has led to a longer fire season, less has been said about how fires have become more catastrophic because there are more homes in their path.

WUI fires fall under the same disaster category as forest fires, the type of blazes that Smokey the Bear wanted us to prevent. But they raise very different policy questions.

Most of the recent action in Sacramento has focused on the latter, aiming to tackle California’s overgrown, parched forests so they are less of a tinderbox when fire rolls in.

Brown convened a task force to address the crisis of millions of dead and dying trees and signed an executive order in May promising to improve forest management. On Sept. 21, he signed a law approving $1 billion to be spent over five years on tree and brush thinning, prescribed burns and other forest health programs.

That spending package, along with a boisterous debate over how utility companies could pass along certain wildfire-related costs to customers, commanded much of the attention in the closing weeks of the legislative year.

But lawmakers also put together a hodgepodge of proposals to address fires in the WUI. Among them was legislation to improve landscaping around homes to reduce fire risk, known as “defensible space,” and to improve emergency alert systems across the state.

It’s those types of efforts that must be at the center of the next governor’s agenda, experts said.

“What the administration is doing now is focusing strongly on the forest-fire component,” said Dan Turner, a former Cal Fire unit chief for San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara and Ventura counties. “There is no equivalent for the wildland-urban interface fires. There’s very little effort going forward in California today on what do we do for solutions for the WUI fire problem.”

On the campaign trail, the gubernatorial candidates have laid out different approaches to wildfire. Republican John Cox has backed more logging to help manage overcrowded forests. Democrat Gavin Newsom has emphasized the links between fire and climate change, and has talked about deploying new technology to detect blazes early.

But there are a number of other policies the next governor will have to weigh. Will it be continued emphasis on vegetation management — thinning out brush and other plants on public land that fuel conflagrations? What about defensible space? The state requires homes in high fire-risk areas to have 100-foot buffers around them, and some counties have stricter requirements, but enforcement can be spotty.

Should the state require buildings to be more fire resilient, with interior sprinklers, double-paned windows and protected vents to guard against flying embers? California law has set stringent requirements for new construction and significant home remodeling in areas with high fire risk. But those rules do not apply to older construction, and making those upgrades can be a costly prospect for homeowners.

What about more money for state and local firefighters? The California Fire Chiefs Assn., for example, sought $100 million in the state budget to shore up the state’s overstretched Mutual Aid System — used by fire agencies to send manpower and equipment to fires outside their jurisdiction — and to enable agencies to pre-position their crews where fire is likely. The final budget included just a quarter of their request: $25 million.

The answer from experts: All of the above.

“Let’s help prepare the battlefield for the firefighters that are in this monumental fight,” said Chris Dicus, a wildland fire expert at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. “From scientists and utility companies to landscape architects and engineers, we have to break out of our silos and come to the table and discuss the fire problem in a multi-faceted and interdisciplinary view — which can be uncomfortable.”

‘It’s not enough’

It usually takes a tragedy to force government to get serious about disaster preparedness. That’s what happened in San Diego.

Fifteen years ago, epic firestorms raged from L.A. County to San Diego. The worst of the blazes was the Cedar Fire, which destroyed more than 2,200 homes and claimed 14 lives. It was followed four years later by a 27-day siege of fire that killed 10 people and destroyed more than 1,700 homes.

The two disasters marked a watershed moment in how the San Diego region grappled with fire.

The county created a consolidated fire agency to oversee about 1.5 million acres. It partnered with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to create a real-time incident monitoring and communication system that is now being used by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, and established a reverse 911 system to call residents with emergency alerts. County and local fire codes were updated with stricter requirements, and local planning departments increased their scrutiny of proposed development. Local nonprofits help residents chip flammable brush.

“It’s day and night. It’s markedly improved,” said County Supervisor Ron Roberts, whose district includes most of the city of San Diego. “Are there more things I’d like to see done? I don’t want to say it’s perfect. But every part of this has improved.”

But airtight regulations mean little without enforcement.

Dianne Jacob, a county supervisor who represents much of San Diego County’s eastern backcountry, acknowledged follow-through could be spotty.

“We’ve got great people out there — the [local nonprofit] fire-safe councils and the county does a lot of these inspections,” Jacob said. But “it’s not enough,” she said, adding that the state could spend more money to help local governments with enforcement.

That hit-or-miss quality of inspection is evident in San Diego’s North County. In affluent Rancho Santa Fe, urban foresters are on staff at the Fire Department. They approve residential landscaping plans, making sure popular but flammable Italian cypress trees and pygmy palms are a safe distance away. The department has nine staff members dedicated to prevention who drive the rustic hills each day and keep an eye on properties to make sure they’re in compliance.

Ten miles away, in Escondido, Ron Woychak, a former firefighter who is now a fire-prevention consultant for developers and homeowners, drove through a new fire-conscious development with wide roads and buildings built to the new code. Directly adjacent were older homes that screamed out risk, with firewood stacked nearby or front porches laden with various flammable tchotchkes.

“We’ve got a lot of homes out here that don’t follow fire code,” Woychak said. “It’s not at the top of their priority list. They’re working, trying to make money, trying to live a life, trying to enjoy their weekends. You think fire prevention is a big thing in their mind? No.”

A political third rail

Are there certain places where it’s simply too dangerous to build?

It’s a simple question, but politically charged. Land use — deciding where to build — has long been the domain of cities and counties. It’s a responsibility local governments doggedly guard.

“The argument is that local control is sacrosanct and we can’t let go of that,” Max Moritz, a wildfire specialist at UC Santa Barbara, said. “It’s almost religious.”

Cara Martinson, a lobbyist with the California State Assn. of Counties, described land use as “inherently local.”

“There is room for the state in these conversations,” she said. “But the approval process really lies squarely with local government.”

Because local governments have a muscular lobbying presence at the Capitol, the prospect of giving the state more authority over land use decisions has for years been seen as a political third rail.

“If you’re really talking major change…we’d be dictating down to locals on fire prevention and mitigation,” said Kim Zagaris, CalOES’s fire and rescue chief. “I’m not sure you’re going to see that. It’s a heavy lift.”

But others in the field say it’s time for the state to take a more active role.

“I’m sure what the local government would say is …we zone and plan accordingly for our local issues,” said Lou Paulson, past president of the California Professional Firefighters. “But when we’ve got to send a massive amount of resources — state-funded and federally-funded — to put wildland-urban interface fires out, it is actually a statewide problem.”

There are signs the state could soon flex more muscle in local land use decisions. Gov. Jerry Brown signed a pair of bills to enhance the state’s role in advising local governments in high fire risk zones.

“There’s an acknowledgement on everybody’s part — the locals in particular — that we need additional technical input and advice,” Martinson said. “Everybody at this point is willing to acknowledge we all need to do better.”

“There is a strong desire on behalf of some people that want to live in these areas and I don’t think we should deny that,” Jacob said. Instead, she said, the government should focus on making sure that homes are built with safety in mind and residents are prepared to accept the risk they’re taking.

Back in Alpine County, Francis, whose life has repeatedly been singed by fire, said she knows and accepts those risks. Even in the emotional days following her close call, she said that if her home burned down, she would remain.

“I suppose people would scratch their heads and say, ‘Why would she build again?’” she acknowledged.

Her answer lies in the living-room view of the ocean and city lights, and quail and rabbits darting across the hill. And in the memories of her now deceased husband.

“Because,” she said, “I love it here.”

Credits: Design and development by Priya Krishnakumar