Alaska salmon may bear scars of global warming

TANANA, ALASKA — With a sickening thud, another hefty and handsome salmon lands in the waste barrel, headed for the dogs.

“See, it’s all of the biggest, best-looking fish,” said Pat Moore, waving a stogie at the pile of discards. “It breaks my heart. My dogs cannot eat all that. The maggots will get them first.”

More Alaskan salmon caught here end up in the dog pot these days, their orange-pink flesh fouled by disease that scientists have correlated with warmer water in the Yukon River.

The sorting of winners and losers at Moore’s riverbank fish camp illustrates what scientists have been predicting will accompany global warming: Cold-temperature barriers are giving way, allowing parasites, bacteria and other disease-spreading organisms to move toward higher latitudes.

“Climate change isn’t going to increase infectious diseases but change the disease landscape,” said marine ecologist Kevin D. Lafferty, who studies parasites for the U.S. Geological Survey. “And some of these surprises are not going to be pretty.”

The emergence of disease in Alaska’s most prized salmon has come as a shock to fishermen and fisheries managers. Alaskan wild salmon has been an uncommon success story among over-exploited fisheries, with healthy runs and robust catches that fetch ever higher prices at fish markets and high-end restaurants in Los Angeles, New York, Tokyo and London.

Fishermen and regulators who have cooperated to save species from overfishing and local environmental hazards have been caught unprepared to deal with forces beyond their control: how to manage a fishery for climate change.

The return of the king -- or chinook -- salmon is eagerly anticipated along the Yukon. The biggest of the salmon species, these kings arrive with a muscular flash of the tail, sun glinting off a speckled palette of blues and greens fading to silver and red.

Savvy buyers from Japan converge on the docks near the river’s mouth to purchase these fish that have bulked up with extra fat to swim more than 2,000 miles, across Alaska, to spawn in the stream of their birth.

As a fierce defender of the fish’s reputation, Gene Sandone, a regional supervisor for Alaska’s Fish and Game Department, was less than receptive to complaints from Tanana fishermen such as Moore that something was wrong.

The chinook salmon they pulled from the Yukon River about 700 miles inland didn’t smell right. It wasn’t an instant, gag-inducing stench. It was more subtle but grew into an unpleasant odor of fruit rotting in the hot sun.

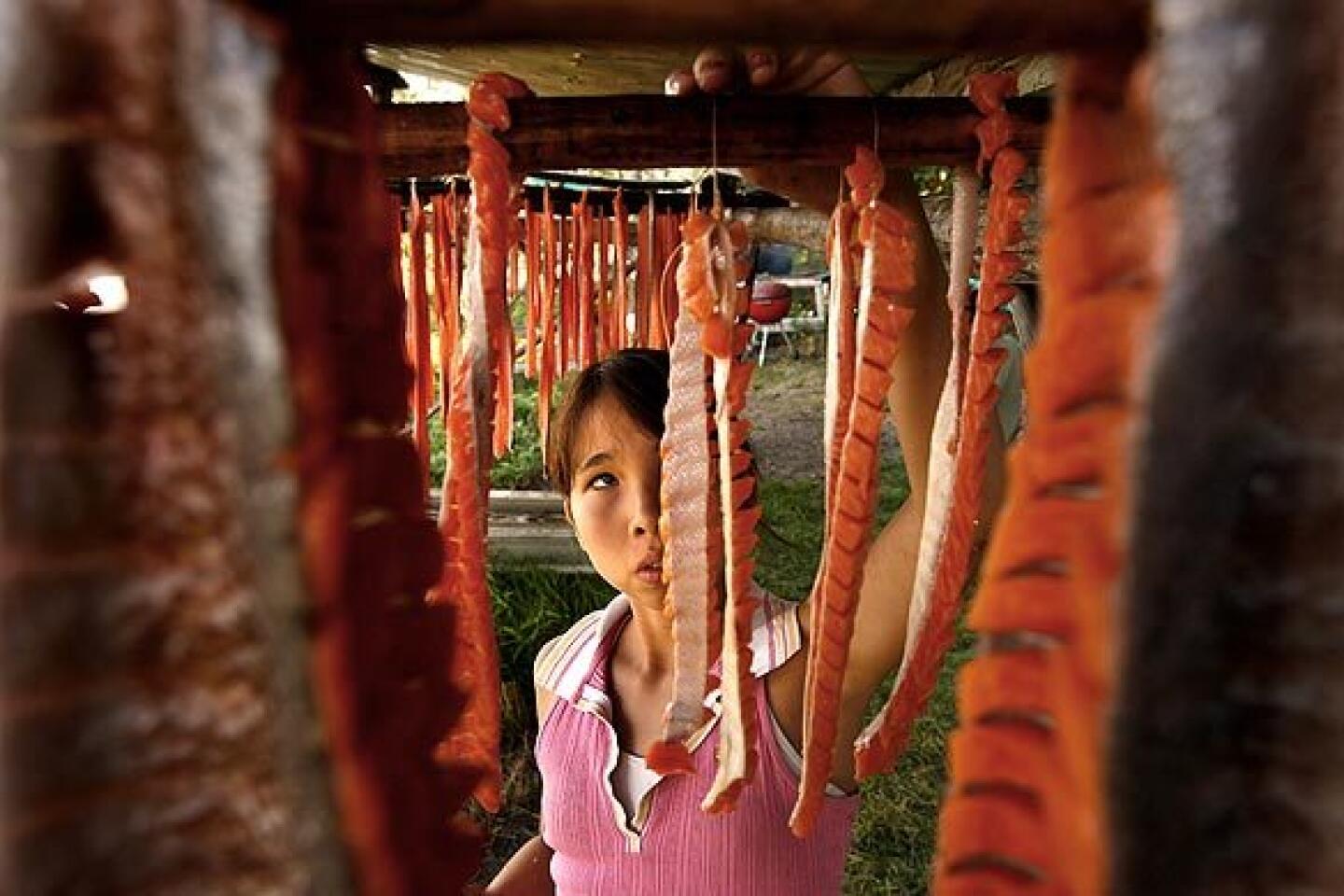

More important, the flesh turned mealy. The salmon didn’t dry right in smokehouses either. Instead of turning into rich red strips of salmon jerky, they turned black and oily like strips of greasy rotten mango.

“If you don’t weed out the bad ones, it’ll stink up the whole smokehouse,” Moore said, wielding a knife on his cutting table. “I only want the good stuff. I don’t want second-rate fish.”

Salmon jerky strips are a staple among the Native Americans and subsistence fishermen in rural outposts such as Tanana, a village of 270 people. “It’ll keep you warm in the winter,” said Lorene Moore, Pat’s wife and a native of the village. In Alaska’s bigger cities, these strips are a prized delicacy, fetching $20 or more a pound.

When Bill Fliris, another Tanana fisherman, first noticed the problem in the late 1980s, he bundled up some salmon jerky strips and shipped them to a state Fish and Game biologist. A few weeks later, the biologist said it was “the damnedest thing -- they disappeared out of the freezer. You know: free strips.”

The next year, Fliris shipped more samples, and this time they were tested. But the state Fish and Game lab found nothing amiss.

A friendly federal biologist advised the local fishermen to send samples, including hearts and organs that were covered with tiny pimples, to the Center for Fish Disease Research at Oregon State University.

The Oregon lab quickly identified it as “white spot disease,” caused by a microscopic parasite called Ichthyophonus hoferi. Ich (pronounced “ick”) is a well-known disease, harmless to humans, that was blamed for devastating losses in the herring fishery in Scandinavia. A similar parasite can infect aquarium fish.

The portion of Yukon salmon with Ich grew each year. Fishermen were throwing away as much as 30% of their catch, forcing them to catch more fish to fill their cache for the winter.

“The Alaskan Department of Fish and Game wasn’t interested,” Fliris said. “They said, ‘There’s no money to study this. It’s a natural disease. There’s nothing we can do about it.’ ”

So Fliris contacted an outsider: Richard M. Kocan, a fish disease expert at the University of Washington. Lining up a federal grant, Kocan began to test the fish in 2000, the same year the king salmon run suffered an unexpected temporary collapse that forced the closure of the river’s commercial fishery.

At the mouth of the Yukon, where the commercial gill netters operate, 25% to 30% of the chinook salmon were infected, Kocan found. But the fish usually did not show signs of the disease.

The same proportion were infected at midriver near Tanana, about halfway to the Canadian border. But here, nearly a third of the fish showed the salt-like flecks on their hearts and other organs, and their mealy flesh released the telltale smell of putrid fruit.

Kocan went upstream to the spawning grounds near Whitehorse, Canada, and found that the proportion of infected fish dropped dramatically. But why? It didn’t seem logical that the fish were recovering during the last part of their stressful 2,200-mile swim, accomplished over many weeks without eating.

“The working hypothesis,” Kocan said, “is that they died before they made it to the spawning grounds.”

Tracking what happens to these fish is difficult. The Yukon turns mocha-brown in the summer, when its swift waters carry a load of rock flour released by rock-pulverizing glaciers and other sediment. Salmon that perish sink out of sight.

To test his theory, Kocan set up a laboratory experiment that compared the swimming stamina of infected rainbow trout with that of healthy trout. He used a chamber with water swift enough to exhaust a healthy fish in about 10 minutes. The infected fish lasted about two minutes. “It’s like asking someone with heart disease to run a 10K race,” Kocan said. “He’s not going to do very well.”

That left a question: Why did the previously undetected disease show up in the late 1980s and resurface every year since?

Kocan and his students scrutinized all the potential variables and found only one significant change: Average river water temperatures had been rising over the last three decades. The warming began earlier each spring, following an earlier breakup of the river’s ice. The June temperatures showed the greatest increase, about 6 to 8 degrees warmer, and June is when king salmon return from the ocean and begin their long upriver migration to spawn.

Unlike warm-blooded animals, the body temperature of salmon fluctuates with the temperature of surrounding waters. Laboratory studies of Ich infections in trout, a close cousin, have revealed that the incidence of disease and death rises as water warms, especially above 59 degrees.

Kocan spent five summers on the Yukon River studying the parasite, creating an uproar among fishermen by sharing his findings directly with them, rather than allowing state Fish and Game officials to review the data first.

He suddenly found his funding drying up after objections from Alaskan representatives on the committee that doles out research dollars.

“I’ve essentially been blackballed from working on the Yukon,” said Kocan, whose work has since been accepted and published in peer-reviewed journals. “There’s one fellow specifically who does not like our results: Gene Sandone. He doesn’t want to hear the story and change his management practices.”

Sandone denied playing any part in this: “I didn’t blackball Richard Kocan. Dr. Kocan is free to put in a proposal and argue his point. He just has to get it through the technical committee.”

The clash comes over the implications of Kocan’s thesis. He believes that as much as 20% of king salmon are dying en route to the spawning grounds. If so, fisheries managers would have to cut back the commercial catch by at least that amount to keep the run healthy.

Sandone has an alternative theory, which has not been tested. He believes that the sick fish, weakened by the parasite, swim along the slower-moving edge of the river, where a disproportionate number get caught by fishing nets and fish wheels that line the banks.

In other words, subsistence fishermen like Pat Moore are simply catching most of the sick fish. The healthy ones swim just out of reach, deeper in the river, headed straight for Canada.

“That’s my theory -- that they are not dying on the way,” Sandone said. “Even if they are dying on the way, so what?” His department limits the catch based on how many fish escape all the nets and make it to the spawning grounds to reproduce.

That’s been going well, he said, except for last year, when the number of fish that made it to Canada fell 50% below the minimum spelled out in a U.S.-Canadian agreement.

Sandone is retiring later this year, after 26 years as a state official. The fishermen in Tanana, who scoff at his theory, say they are delighted to see him go. They hope the state will be less hostile to studying the disease and trying to figure out what to do about it.

Besides supporting fishermen, salmon are a keystone species in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, supporting wildlife from birds to bears and orcas.

A crash could cripple dependent creatures.

Mary Ruckelshaus, a federal biologist with the Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle, has been running climate models to peer into the future for Pacific Northwest salmon. Those models predict that salmon will become extinct without aggressive efforts to preserve the clear, cool streams needed for spawning, such as planting trees to shade streams and curtailing the amount of water siphoned off by farmers.

“It’s sort of a time bomb,” Ruckelshaus said.

“If people don’t have a plan for it, it can be disastrous when it hits.”

Her models didn’t factor in the potential for emerging diseases, such as the one that Kocan, her former professor, has been studying.

Kocan views Ichthyophonus as a classic emerging disease. He pointed out that salmon, a lucrative catch, had been scrutinized by scientists and fishermen for decades, and the disease had never before been reported. In the last decade, it has shown up in salmon on the Yukon, Kuskokwim and Taku rivers in Alaska and on various rivers in British Columbia and Russia.

It has also been detected in recent years in rockfish and smaller noncommercial fish in Puget Sound and elsewhere off the coasts of Oregon and Washington, and in freshwater trout on Idaho farms.

It’s the kind of redistribution of disease that can be expected with climate change, Kocan said: “Everything is getting warmer, and that’s how climate change is going to redistribute all kinds of disease. Parasites have their optimum conditions -- upper and lower limits. We’ll notice where they show up but not necessarily where they disappear.”

Ichthyophonus is among a class of ancient parasitic microbes that can move fast, taking advantage of new niches using age-old tricks that have kept them around for billions of years.

None of this comforts Pat Moore, a musher with dozens of dogs, and others who rely on the bounty of the Yukon River to make their living. It’s a culture that lives on the edge and cannot stomach waste.

“I don’t want to kill fish for the sake of killing them,” said Moore, as he expertly sliced a king into narrow strips.

“I want to use the damned things.”