How teaching kids about climate change can influence their conservative parents

- Share via

You could say kids are taking the lead on climate change.

Greta Thunberg, a 16-year-old Swedish activist and Nobel peace prize nominee, has barnstormed parliaments and United Nations meetings, calling on leaders to stop “behaving like children” and get serious about tackling climate change.

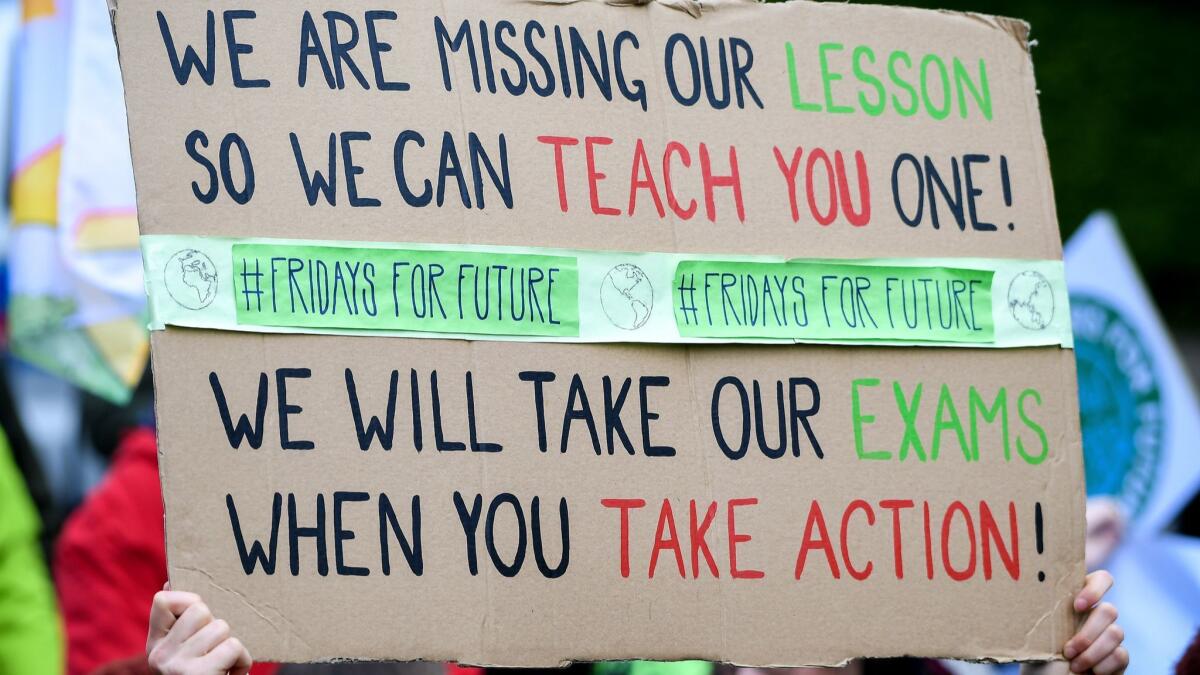

Following Thunberg’s lead, thousands of students around the world have started skipping school on Fridays to protest climate inaction. And in June, a group of young Americans will face off against the U.S. government in a landmark trial aimed at spurring more aggressive efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

But kids can change the climate conversation at home too, according to a study published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Researchers found that teaching children about climate change in school significantly increased their parents’ concern over the issue. Notably, the effect was strongest among conservative parents — who tended to be the least worried about global warming, and whose views have historically proven difficult to influence.

Danielle Lawson, a social scientist at North Carolina State University and lead author of the study, said the results made her feel hopeful.

“Not only are we teaching kids in a way that prepares them for the future — because they are going to have to deal with the brunt of climate change — but it continues to empower their efforts to help bring all of us together to work toward solutions,” she said.

Previous experiments have shown that educating kids can spur changes in parents’ recycling habits and energy-saving behavior. Lawson and her colleagues wondered whether the same would apply for climate change.

The researchers worked with 15 teachers as they taught nearly 250 middle school students in coastal North Carolina, which will face rising sea levels and stronger storms under climate change.

In some of the classes, students worked on four activities centered on the connections between climate change and local wildlife. They also participated in a community-based project and conducted an interview with their parents about the changes in weather they had observed in their lifetimes.

Students in the other classes did not receive the climate change curriculum, and they served as a control group.

To see how attitudes changed as a result of the program, the researchers surveyed both students and parents at the beginning and the end of the 2016-17 and 2017-18 school years.

They found that students who completed the climate change module became more concerned about the issue than their counterparts in the control group. On a 16-point scale, their concern rose by 2.78 points, compared to 0.72 points in the control group.

The effect was even stronger among parents. Concern rose by rose 3.89 points for those whose kids learned about climate change in class, versus 1.37 points for parents whose kids did not.

But the most striking thing about the new study was that the lessons had the biggest effect among conservative parents, whose concern increased by 4.77 points, said John Cook, a climate communication researcher at George Mason University who was not involved in the study.

Surveys show that conservative Americans are least likely to be concerned about climate change, and efforts to sway them often backfire. That’s because people’s views are strongly shaped by group identity, particularly their political affiliation, Cook said: “If you change your mind on something where all of your tribe believes the same thing, you risk social alienation.”

Letting kids lead the conversation seems to make the issue less polarizing, he said.

Lawson said she thought that was because children don’t usually approach climate change from an ideological perspective. Another factor is “that unique relationship between a parent and their child, and this level of trust,” she said.

The most famous example of this involved Bob Inglis, a Republican congressman from South Carolina. After Inglis’ college-age son took a course in environmental economics, he persuaded his father to reconsider his position. In 2009, Inglis broke ranks with his party and proposed a bill to help reduce carbon emissions. (He lost his reelection bid in 2010, partly as a result of his stance on climate change, and now works to promote free-market climate solutions).

The researchers also found that concern increased more than average among fathers. The same was true for parents of daughters. This could be due to the fact that, compared with boys, girls expressed greater worry about climate change after the lessons. Another possible factor is that during the middle school years, girls typically communicate better than boys, the study authors said. (For reasons that remain unclear, parents of daughters started out less concerned than parents of sons.)

Experts said the program’s success had a lot to do with how teachers tackled climate change in the classroom.

“Reading a textbook and completing a worksheet are unlikely to entice students to comment on their day at the dinner table,” Martha Monroe, an expert on environmental education at the University of Florida, observed in an essay that accompanied the study.

Instead, Lawson and her team designed hands-on lessons focused on local issues. For example, one assignment involved monitoring the weather outside the school and comparing it with historical data for the region.

The students’ projects mostly focused on North Carolina’s coast. Some students helped monitor sea turtle nests, since the gender of hatching eggs depends on temperature, while others helped build oyster reefs that can protect the shore from erosion and sea-level rise.

Those activities may have translated into more parental engagement, Lawson said. “If you can get kids so excited and talking with their parents about what they are learning in schools, parents will want to learn.”

The researchers wanted the interactions to arise organically, so the curriculum did not ask students to try to change their parents’ minds. “We do not want to put that burden on small shoulders,” she said.

When teaching climate change, tackle the myths along with the facts, researchers say »

Other educators are already using similar approaches in their climate lessons.

“To me, the key thing is having them discover it on their own,” said Rebecca Brewer, a high school biology teacher in Troy, Mich. Every year, Brewer spends a week making imitation ice cores in her freezer, which her students cut up and measure while they study scientific data on past climate changes.

“I’m not standing at the front of the room saying, ‘Climate change is real,’ ” she said. “You are going to examine the evidence and see for yourself.”

Jeremy Cook, a biology teacher in Indianapolis, Ind., (not related to John Cook) has his students investigate how climate change is bringing more invasive species to the area. “I think that’s really eye-opening for them,” he said. “It’s not just about weather patterns changing.”

Researchers and educators say these types of lessons are not about activism or advocacy. Teachers are simply giving students the facts.

“We are not telling them what to think or what to say,” Lawson said.

Even so, the classroom has become a battleground in the fight to sway public opinion over climate change.

Conservative state legislators around the country have introduced more than a dozen bills that could make it harder to discuss climate change in classrooms, or would allow teachers to present it as an issue that’s up for debate. (It’s not.) So far, none of these measures have become law.

Today, science standards in 36 states acknowledge that climate change is real and due to human activities, but only 42% of teachers surveyed in a recent NPR/Ipsos poll said they tackled the subject in their classrooms. A third of them expressed fear of blowback from parents.

But parents overwhelmingly seem to want their kids to learn about climate change. The same poll found that 80% supported climate education in schools.

The new study demonstrates why that could have profound societal effects.

Kids don’t have a lot of monetary or political power. But if “we give them a place to have a voice,” Lawson said, “they can bring us together.”