Coronavirus Today: Farewell to California’s state of emergency

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Feb. 28. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

My fellow Californians, when you wake up tomorrow morning, you will no longer live in a state that’s in a COVID-19 state of emergency.

Will that make the sky seem more blue? The air smell more clean? The traffic less arduous?

In all likelihood, the answer is no. In fact, you’ll be hard-pressed to notice a single immediate change in your daily life.

Gov. Gavin Newsom declared the state of emergency on March 4, 2020, to give Sacramento more flexibility to respond to the mushrooming coronavirus health crisis. At the time, there were 53 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and one known death. But hundreds of other residents had recently disembarked from a coronavirus-infested cruise ship, and there were early signs that the virus had begun spreading in the community.

Newsom and his advisors feared the outbreak would soon overwhelm the healthcare system. The state of emergency gave the governor authority to commandeer hospitals and medical labs, along with other private property such as hotels and motels. It also provided legal cover for him to “make, amend and rescind state regulations, suspend state statutes and redirect state funds,” my colleague Taryn Luna explained.

Although the state of emergency made Newsom’s job easier, the last three years haven’t been without setbacks. Even members of the governor’s own party complained about his broad use of power, including mask and vaccine mandates and onerous restrictions on how businesses could safely operate.

Newsom didn’t always help himself. Remember when he said his children were transitioning back to in-person learning at their private school while public school students throughout the state were still struggling with distance learning? Or the time he was caught dining at Napa Valley’s exclusive French Laundry restaurant with members of more than three other households — including a lobbyist friend — when he was asking Californians not to see their extended family members for Thanksgiving?

Missteps like these fueled the 2021 recall election, which Newsom won by a margin of 62% to 38%.

Altogether, Newsom issued more than 70 executive orders to facilitate California’s COVID-19 response, including ones aimed at ramping up testing centers and vaccination clinics. Most of those orders had been revoked by last fall, when Newsom announced his intention to wind down the state of emergency.

Thanks to state legislators, health insurers in California will have to keep paying for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments after the state of emergency ends (though come November, patients will have to get them through their insurance networks). The cost of at-home coronavirus tests will be covered until November.

Californians without insurance will also maintain access to COVID-19 necessities after today. They’ll be able to get their hands on the medicines and vaccines in the federal government’s stockpile until the summer, and possibly beyond.

But it may not take that long for them to notice some changes in the post-state-of-emergency world. COVID-19 care may remain free, but finding it could become more difficult — and that kind of barrier could wind up hurting everyone, said Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of UC San Francisco’s Department of Medicine.

“If you have a situation where more people are sick, feel sick, don’t know what they have, potentially are going into work and exposing themselves to other people and probably should be on Paxlovid, but don’t have access to it, that’s all bad,” Wachter told Luna. “In a perfect world, that wouldn’t happen.”

Newsom expressed confidence that the public’s health could be maintained without continuing the state of emergency.

“California is better prepared and that’s because we have a serious Legislature and the health ecosystem in California is second to none in the country,” he said.

That’s probably not the only reason to let the state of emergency wind down, said Jack Pitney, a professor of American politics at Claremont McKenna College: “I think Gov. Newsom, like pretty much everybody else in California, is really sick of dealing with COVID.”

You can add Los Angeles County to that list. With hospitalization and death rates now stabilized at a manageable level, the Board of Supervisors voted unanimously Tuesday to end the county’s 3-year-old COVID-19 emergency declaration on March. 31.

“COVID is still with us, but it is no longer an emergency,” said Supervisor Janice Hahn, who co-wrote the motion with Supervisor Kathryn Barger. “It’s time for us in L.A. County to end our emergency orders.”

By the numbers

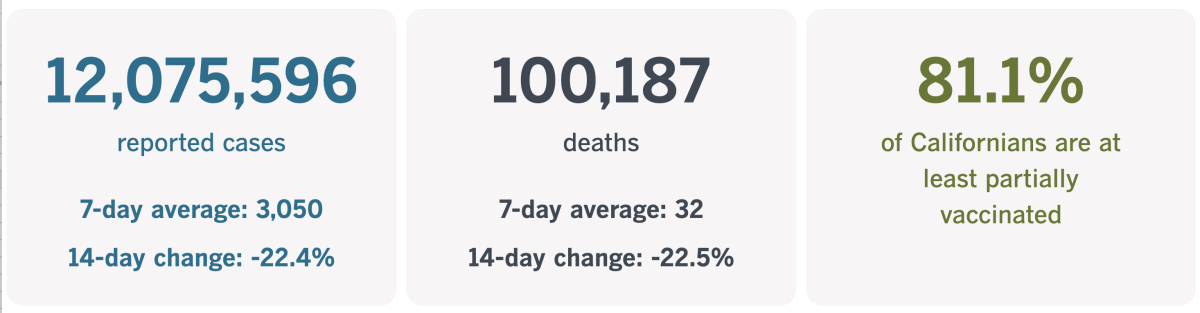

California cases and deaths as of 5 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

How COVID-19 fuels another killer

As of Tuesday, COVID-19 is killing about 2,400 Americans per week. But let’s shift our focus to another condition that kills more people in this country each year than breast cancer, opioid overdoses and HIV/AIDS combined — sepsis.

Sepsis occurs when the body has an extreme reaction to an infection that winds up harming healthy cells. The toxic chain of events can cause blood clots to form, blood vessels to leak, and crucial organs like the lungs, liver and kidneys to fail. Unfortunately, it often goes unnoticed in its early, most treatable stages because its symptoms — including fever, clammy skin and shortness of breath — are shared by many conditions. By the time it’s clear that sepsis is the culprit, treatment is more difficult.

One-third of patients who die in hospitals have sepsis, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It usually starts with a bacterial infection, but viruses can trigger it too. That includes the one that causes COVID-19.

Perhaps you can see where this is going.

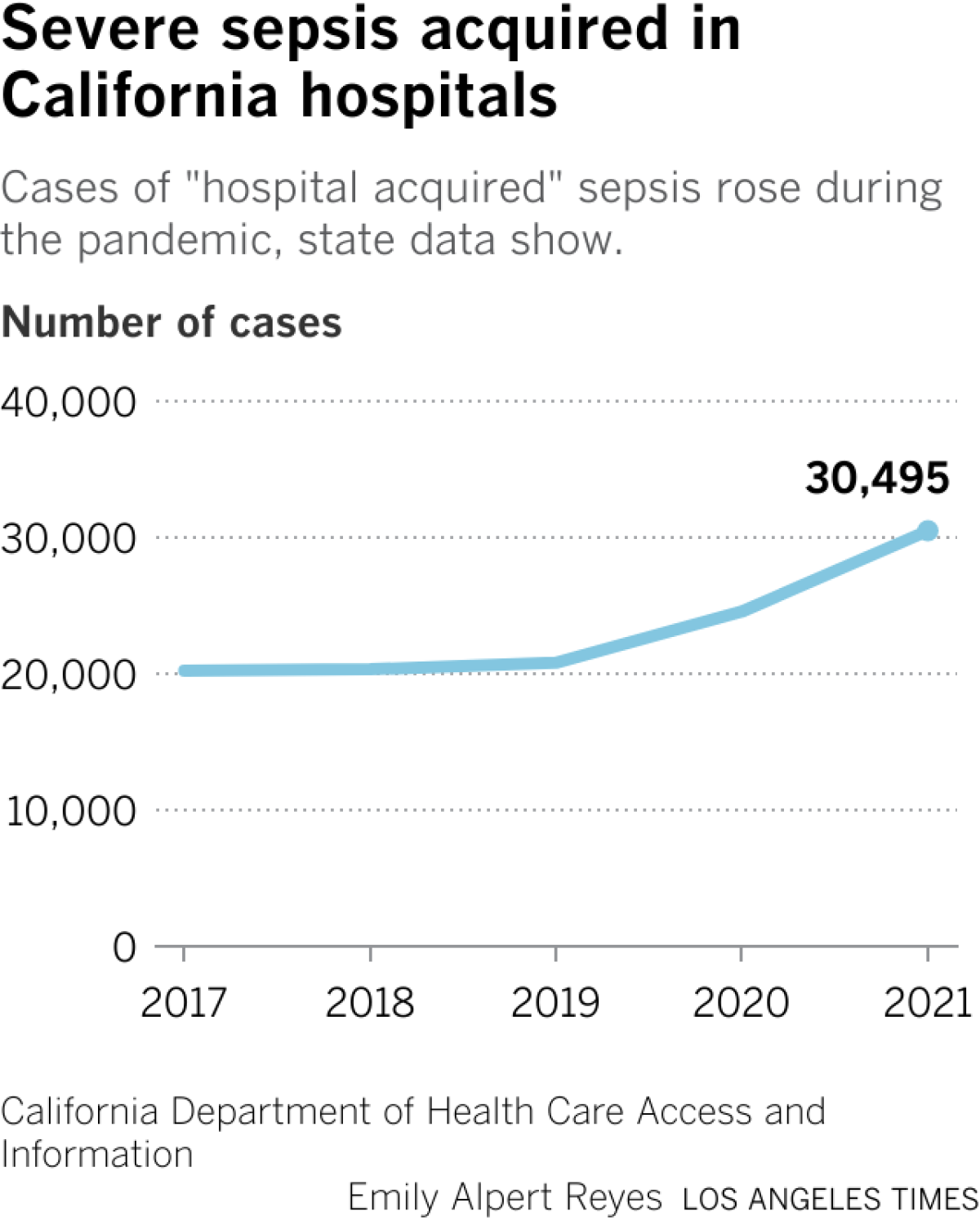

Cases of severe sepsis have been rising in California hospitals since the pandemic began, according to state data. In 2021, for instance, nearly 40% of hospitalized patients who died of severe sepsis had COVID-19.

“Sepsis is a leading cause of death in hospitals. It’s been true for a long time — and it’s become even more true during the pandemic,” Dr. Kedar Mate, president and chief executive of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, told my colleague Emily Alpert Reyes.

It’s not just that the pandemic has caused more than 12 million infections in California alone. It has caused thousands — sometimes tens of thousands — of Californians to be hospitalized with coronavirus infections on any given day. Simply being in a hospital makes a person more vulnerable to sepsis.

“The longer you’re in the hospital, the more things happen to you,” Dr. Maita Kuvhenguhwa, an infectious disease doctor at MLK Community Healthcare, told Alpert Reyes.

“You’re immobilized, so you have a risk of developing pressure ulcers and the wound can get infected,” Kuvhenguhwa said. “Lines, tubes, being here a long time — all put them at risk for infection.”

Nearly 9 times out of 10, an infection that leads to sepsis begins outside the hospital, the CDC says. But 13% of sepsis patients catch their fateful infection after they’ve been admitted. The pandemic created a lot more hospitalized patients, and the number of people who developed severe sepsis from a hospital-acquired infection increased by more than 46% between 2019 and 2021, state data show.

To make matters worse, the steps taken by hospital staff to limit coronavirus spread may have disrupted their usual methods of infection control. On top of that, some traveling nurses hired to cope with patient surges were less familiar with the infection-prevention routines in their temporary workplaces.

Still, the COVID-19 surges didn’t help. With overwhelmed nurses strapped for time, patients might have waited longer to get their catheters changed (potentially leading to more urinary tract infections). Checks of their mouths (to prevent bacterial infections) probably became less frequent as well.

Rules that kept family members out of hospitals may have played a role too, said Armando Nahum, a founding member of Patients for Patient Safety U.S. If visitors had been permitted, they might have noticed unusual symptoms in their loved ones and alerted caregivers earlier, he said.

This trend wasn’t unique to California. Hospital-acquired infections increased nationwide in the pandemic years, especially during COVID-19 surges, researchers have found.

If there’s one positive thing to say about the recent rise of sepsis, it’s that experts have already figured out ways to reverse it.

After a 12-year-old boy in New York died of sepsis in 2012, hospitals throughout the state were required to implement new protocols to speed the process of identifying and treating sepsis patients. The New York State Sepsis Care Improvement Initiative saved more than 16,000 lives between 2015 and 2019, according to the state’s health department. Independent health researchers agreed that sepsis deaths declined more in New York than in states without such protocols.

Jefferson Health, a health system serving parts of Pennsylvania and New Jersey, adopted its own sepsis-control measures in the fall of 2021. Among other things, the system uses information from patients’ electronic medical records to predict which ones might have sepsis, then alerts clinicians so they can investigate. If a patient does have sepsis, a new set of standardized protocols makes it less taxing for doctors and nurses to begin treatment as quickly as possible.

The result: Deaths due to severe sepsis fell by 15% in one year.

Lindsey Lastinger, a health scientist in the CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, is hopeful that hospitals across the country can find ways to reverse the recent increase in sepsis deaths. “This setback can and must be temporary,” she said.

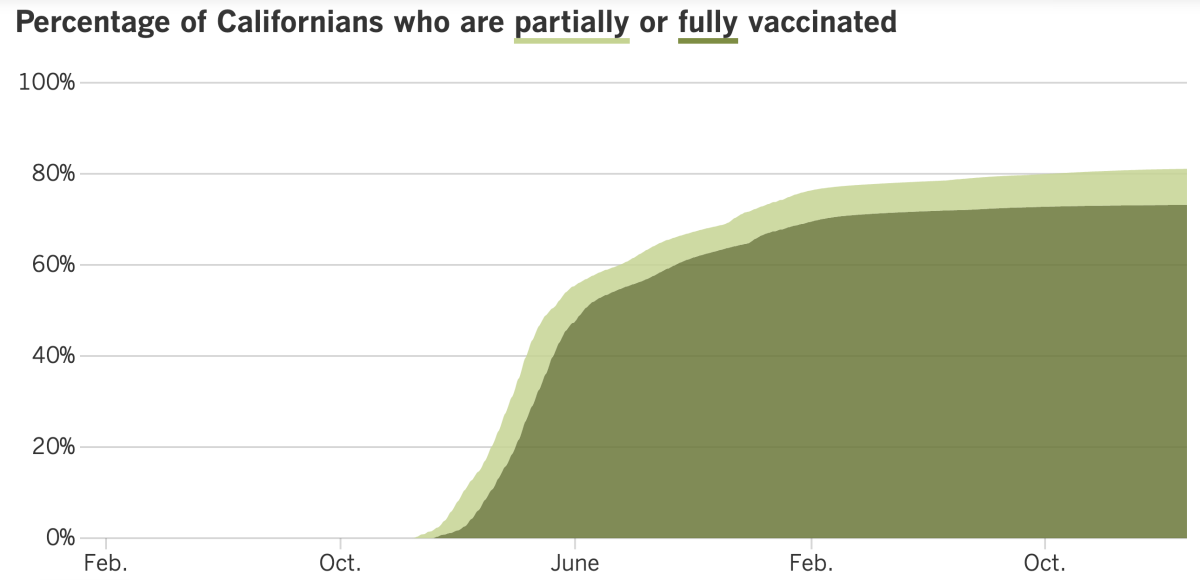

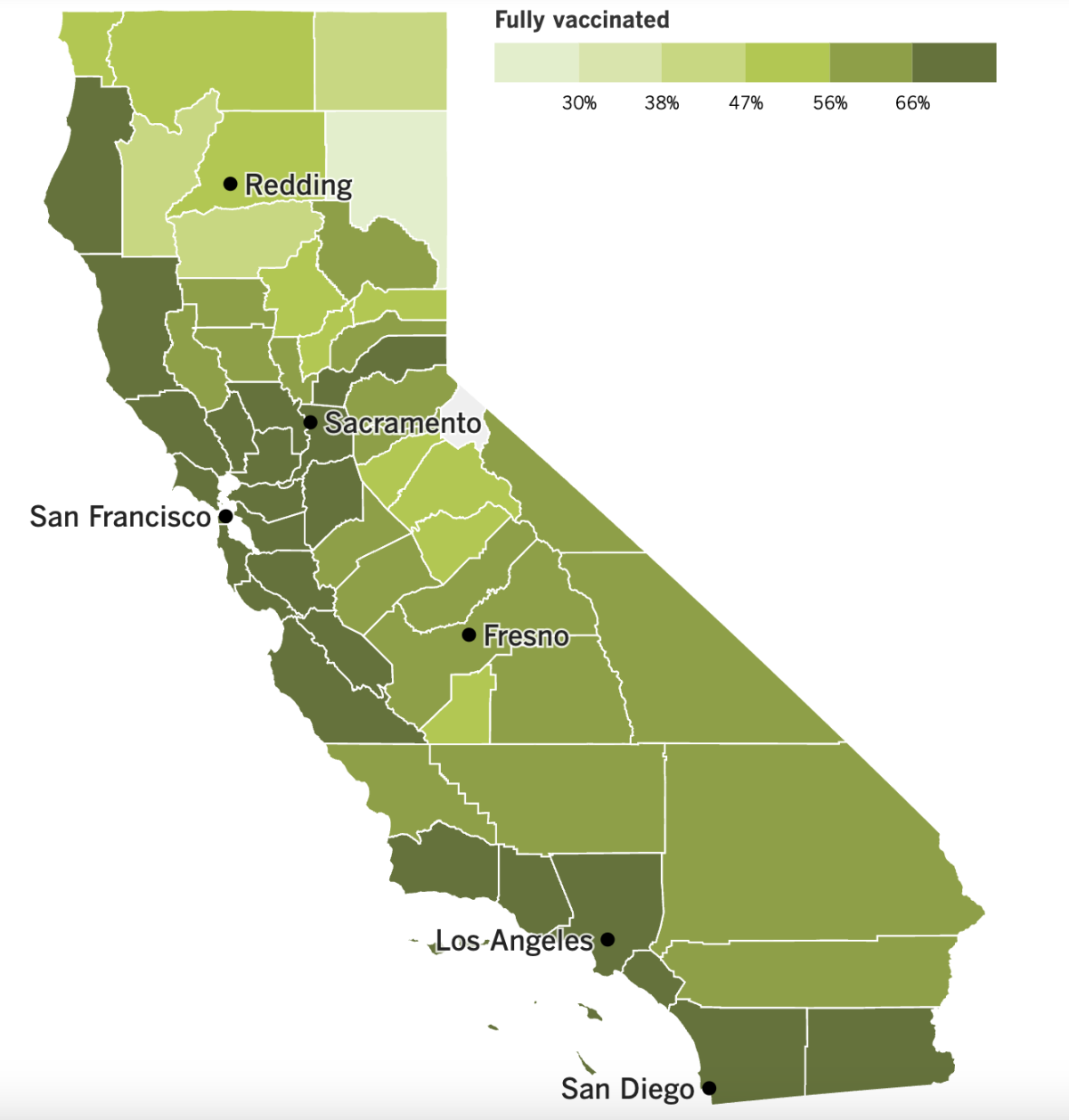

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

It’s happened: California has become the first state to record 100,000 COVID-19 deaths.

It can be hard to wrap your mind around a figure like that, so think of it this way: The number of Californians who died because of the pandemic exceeds the population of 529 cities in the Golden State.

The losses here account for 9% of America’s 1,115,637 COVID-19 casualties. Considering that California is home to 11.7% of U.S. residents, that’s a bit of a silver lining.

In fact, if you compare states according to their COVID-19 mortality rates, California’s 255.3 deaths per 100,000 residents is the 11th-lowest in the country. Ten states — Arizona, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Tennessee, West Virginia, Arkansas, New Mexico, Alabama, Michigan and Florida — have logged at least 416 COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 residents.

Even to those who have been fighting the virus nonstop since it arrived in California in January 2020, this grim milestone is hard to believe.

“Nobody, I think, anticipated this toll,” said Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer. “None of us wanted this to lead to so many people losing their lives, and it creates great sadness. It’s hard for our community to recover.”

Despite the widespread availability of vaccines and treatments, the deaths are still coming. More than 2,200 Californians have died of COVID-19 in 2023, and as of Tuesday, that figure is growing by an average of 32 each day, according to The Times’ tracker.

As my colleague Luke Money so eloquently put it, “virus’ cumulative devastation remains hard to comprehend while its day-to-day effects are, for many, increasingly easy to ignore.”

Indeed, signs of our collective inclination to stop focusing on the pandemic are everywhere.

Newsom intends to have the state stop paying for the medical services offered to asylum seekers and other migrants who are brought to screening centers near the border with Mexico. The centers — two in San Diego County and one in Imperial County — have offered COVID-19 vaccinations, testing, face masks and other health services to more than 300,000 people since they opened in April 2021. But with a projected budget deficit of $22.5 billion, the governor said the state can no longer afford to foot this bill.

The medical screening centers also receive funds from federal and local sources, and Newsom told our friends at KHN that he’s had “some remarkably good conversations” with members of the Biden administration about the possibility of making more federal funds available to pick up the slack. One potential source of new dollars may come from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, which has set aside $800 million for grants to provide shelter and services.

California started paying for medical services at the shelters two years ago, during the pandemic’s first devastating winter surge. In addition to COVID-19 care, the centers treat chronic health problems like diabetes and high blood pressure. They also take care of injuries sustained by migrants on their way to the U.S. border.

The people who operate the clinics are hopeful that replacement money will materialize from somewhere. “We’re continuing our operations and again calling on all levels of government to make sure that there is an investment,” said Kate Clark, senior director of immigration services for Jewish Family Service of San Diego.

Here’s another sign that many of us have left the pandemic in our rearview mirrors: About 110 hospitals and 750 nursing homes around the country were caught violating the federal vaccination mandate for healthcare workers in the last year. That amounted to about 2% of the nation’s hospitals and 5% of nursing homes.

An estimated 10 million people who work at facilities that get money from Medicare or Medicaid are subject to the mandate, which went into effect a little more than a year ago. It applies to employees, contractors and volunteers and is supposed to remain in effect until November 2024. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said the mandate “saved Americans from countless infections, hospitalizations, and death.”

Yet Texas, Florida and other states didn’t check to see whether healthcare facilities were in compliance. So CMS hired contractors to do it for them, a move that cost Texas more than $2.5 million and Florida more than $1.2 million.

Now nursing homes are pushing to lift the vaccination mandate altogether. They say it has made it all but impossible to find enough willing workers, and the resulting staff shortages have forced more than half of them to turn away patients they’d otherwise admit, according to a trade group that represents long-term care facilities.

“Their regulations are making it harder to give care — not easier,” said Tim Corbin, the administrator of Truman Lake Manor in rural Missouri, which granted religious exemptions to more than 40% of its workforce and still managed to be cited because three employees who got a first dose of COVID-19 vaccine didn’t go back for the second shot.

In December, one of the unvaccinated employees touched off an outbreak that spread to 26 of the home’s 60 residents and to about 25% of the staff. Despite this, Corbin insisted that “the mandates need to end.”

Perhaps nursing homes are having trouble finding employees because the people who normally would be looking for jobs have left the labor force. Economists say millions of people have gone missing from the labor pool since the pandemic began, and they aren’t sure where they all went.

Various attempts to solve the puzzle have estimated that 2.1 million people retired early because of the pandemic and that the number of immigrants taking jobs in the U.S. fell by about 2 million. Long COVID has kept another 1 million or so would-be workers at home, and roughly 400,000 working-age Americans are out of the labor force because they died of COVID-19.

But it’s not clear just how much the workforce has shrunk as a result of the pandemic, and that uncertainty makes it difficult for the Federal Reserve to set monetary policy.

“It’s a very confusing picture,” said Anna Wong, chief U.S. economist at Bloomberg Economics. “We don’t even have good facts to work with.”

Speaking of confusing pictures, the U.S. Department of Energy has determined that the pandemic was sparked by an unintentional lab leak in China, though it has only “low confidence” in this assessment, according to a report that has not been made public. The sources who described the report’s conclusions did not share the evidence that supports the DOE’s claim.

This means the FBI now has some company in the U.S. intelligence community. In 2021, the bureau said with “moderate confidence” that a lab leak was to blame. But at least four other intelligence agencies have determined — with “low confidence” — that the SARS-CoV-2 virus jumped from an animal to a human, and the DOE’s findings don’t seem to have swayed them, officials said.

“There is not a consensus right now in the U.S. government about exactly how COVID started,” said John F. Kirby, the spokesman for the National Security Council.

Some scientists haven’t ruled out the possibility of a lab leak, but many researchers agree that the strongest evidence points to at least one instance of animal-to-human transmission at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan. Without more cooperation from China, however, we may never have definitive proof of how the global outbreak began.

For its part, China continues to insist that it’s been “open and transparent” with investigators.

And finally, Woody Harrelson is in hot water for dissing COVID-19 vaccines and other pandemic safety measures when he hosted “Saturday Night Live” this weekend.

In his opening monologue, Harrelson described a movie script he supposedly read in November 2019. In the movie, “the biggest drug cartels in the world” joined forces so they could “force all the people in the world to stay locked in their homes, and people can only come out if they take the cartel’s drugs.” He said he tossed the script, because “who was going to believe that crazy idea?”

Harrelson has been known to trade in COVID-19 conspiracy theories, and his monologue prompted fact-based viewers to defend the truth on Twitter.

“That was some anti-vax nonsense,” tweeted one viewer. Another called the shtick “irresponsible” while a third wondered “who at NBC “approved this?”

Among the more pointed critiques was this one from @drosslmyers: “F— you for giving this dude a platform to spread this anti-vax [BS]. call me a bad sport or whatever but i don’t think it’s funny when we’re still in the midst of an illness that’s still spreading thanks to losers like this.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: It’s been six months since my last booster shot. Is there a plan in place for the next round?

This question is extremely similar to one I answered a few weeks ago, about when readers could get their second dose of the bivalent booster shots that target Omciron. I try not to repeat a topic, but the email in our inbox tells me a lot of you are still wondering about this — especially since tomorrow marks six months since the day the CDC endorsed the updated boosters.

As it happens, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices considered this very issue at a meeting on Friday. The committee members discussed ways to simplify the COVID-19 booster schedule, including a plan to offer the shots once a year in the fall (like flu shots). The formula for the COVID-19 booster could be tweaked each year to match the coronavirus variants in circulation at the time (also like flu shots).

The committee members acknowledged that certain groups — such as elderly adults who face the greatest risk of becoming seriously ill and people who are immunocompromised — may benefit from more frequent boosting. However, they said they don’t have enough information right now to say how much more frequent their boosting should be. The meeting adjourned without any votes being taken.

Essentially, the CDC is in the same boat as the Food and Drug Administration. The FDA has suggested making COVID-19 boosters an annual affair for most people, with more shots available to people in high-risk groups. Members of the FDA’s vaccine advisory group said last month that they needed to see more real-world data before they could determine an ideal dosing schedule.

It’s not clear how long it will take either the FDA or the CDC to decide on the timing for the next COVID-19 booster shot. The FDA advisory committee is convening this week to discuss potential vaccines aimed at respiratory syncytial virus, then again next week to select influenza strains for this fall’s flu shot. So far, COVID-19 is not on the agenda for either meeting. The CDC’s advisory committee has not yet scheduled its next meeting.

So if you’re among the 16.1% of Americans who have already received the bivalent booster, the CDC considers you up to date. All you can do now is sit tight.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

The women in the photo above are learning how to make floral arrangements. What’s unusual about the class is where it’s being taught, and who’s paying for it.

The lesson took place at the Water Garden office complex in Santa Monica, and it was hosted by CBRE, the commercial real estate firm that manages the property. CBRE has also been footing the bill for musical performances, art exhibitions and comedy shows.

If all that makes the Water Garden sound like an appealing place to work, then the firm’s investment is paying off. You’ve already read about the amazing perks employers are using to lure workers back into their offices. Now my colleague Roger Vincent reports that landlords are using some of the same strategies to attract tenants.

It’s working. The Water Garden is now 86% leased, up from 72% a year ago.

The landlord of U.S. Bank Tower, L.A.’s tallest office building, is pursuing a similar strategy. As part of a $60-million makeover, Silverstein Properties is turning the 54th floor into a tenants-only lounge with a coffee bar and offering yoga-with-a-view at the 57th-floor gym.

“The goal is to get people to feel like they want to come back to work and come back to the building,” said tenant experience manager Melanie Navas, “and having them leave happy.”

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.