Ancient baby boom in American Southwest exceeded modern birthrates

The grandeur of Mesa Verde’s cliff-side dwellings and the awe-inspiring engineering feats of Chaco Canyon attest to the vibrant cultures that flourished in the American Southwest more than 1,000 years ago. At these sites, ancient civilizations monitored the motions of the cosmos, developed sophisticated agricultural techniques, and apparently had lots of babies.

In a new study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists say that at the height of their prosperity between AD 500 and 1000, birthrates among neolithic Native Americans likely exceeded the highest birthrates on Earth today.

Neolithic birthrates then fell early in the next millennium as populations shrank and entire civilizations abruptly disappeared from northern sites like Chaco Canyon for reasons that have long confounded archaeologists.

Broadly, this baby boom tracked the transition of early Americans from hunter-gatherers to sedentary agriculturalists. Tim Kohler, an archaeologist at Washington State University in Pullman and an author of the study, gives several reasons why putting down roots leads to more offspring.

One major factor is that if a woman doesn’t have to carry her children on her back while she migrates following food, she can have more than one dependent child at a time. Also, farmers have greater access to nutritious foods that allow babies to stop nursing sooner.

“You can take corn and grind it up and make a porridge and that makes a great weaning food,” Kohler said. Earlier weaning allows the mother to start ovulating and become pregnant again.

Such food-driven population changes have occurred all over the world; a famous population boom and bust happened in Europe during the rise of agriculture, although it occurred several thousand years earlier and much faster than in the Southwest.

“I think this stems from the fact that it was a fully developed agricultural package of crops and animals that was introduced to Europe,” said Stephen Shennan, an archaeologist at University College London who has worked on the European transition. In the Southwest, the diversity of agricultural crops and technologies evolved over the course of centuries, first with the arrival of maize, then beans, then bows and arrows, and finally, ceramic pots for storage.

To study the anatomy of the agricultural revolution in the Southwest, Kohler and graduate student Kelsey Reese took a nontraditional approach: Instead of focusing on dwellings and physical objects left behind by these vanished peoples to estimate their group size and habits, they reconstructed a reproductive history by studying human remains.

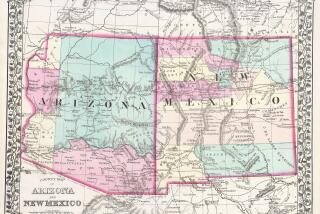

Kohler and Reese compiled previously published data from 194 archaeological sites scattered across the Southwest that together document the deaths of more than 10,000 people who lived between 1100 BC and AD 1300. By determining the age distribution of the deceased in each burial assemblage, they were able to estimate the youthfulness of that population — which has been shown to reflect birthrates — over time for 10 subregions of the Southwest.

“It’s a very creative approach to answer this demographic question,” said William Doelle, president of Archaeology Southwest, who was not involved in the study. “This is a real leap forward.”

Overall, the study’s picture of gradually rising birthrates that peak around AD 1000 agree well with the population estimates Doelle has generated based on traditional studies of buildings and artifacts. But when Kohler and Reese looked at the patterns in their data, what they found surprised them: Birthrates at individual sites varied dramatically between regions and over time.

“One of the things we were able to show is that birthrates are much lower for sites in irrigated areas than they are in the dry farmed areas in the north,” Kohler said. “That is unanticipated and we need to try to figure out why.”

While this might seem counterintuitive, Kohler offers some tentative explanations. The irrigated regions, which cluster in the south near the places we now call Phoenix and Tucson, could not have expanded without significant investment in infrastructure, he said. This would not have been the case on the Colorado Plateau in the north where large areas of land became suitable for cultivation under favorable climate conditions.

Kohler also cites another factor that might have held birthrates in irrigated societies in check: If they were drinking the water from their canals, it almost certainly would have teemed with pathogens. However, Kohler says this hypothesis will be hard to test using archaeological data.

Irrigated areas also could have sent their youth abroad, reducing their representation in burial sites, but Kohler said there is little evidence for this either.

The reason these variable local histories add up to the smoothly growing birthrate of the Southwest as a whole, Kohler thinks, is that populations weren’t really fluctuating wildly, they were just moving around when times got tough. Until they couldn’t.

“At a certain point,” Kohler said, “population levels get high enough so that all the good places for agriculture are claimed up. You can’t move someplace else without bumping into somebody who’s already there. People have to stay put and suffer the variability that they endure by having to stay put.”

He thinks this could be the reason for the oscillations in birthrates that begin around AD 1000 and presage the precipitous drop at 1300 — the Southwest simply filled up.

This decline has previously been attributed to severe drought, but the new details unveiled by Kohler’s study show that areas with high birthrates that eventually depopulated started to exhibit signs of trouble beforehand.

Kohler said he thinks overpopulation could have played a significant role in the fall of the northern civilizations, with climate change tipping the scales.

“I doubt that it’s coincidental that the areas with the highest birthrates are the ones that people had to abandon,” he said. He plans to delve into exactly why in the coming year.

Overall, Kohler called these results “sobering.” While they don’t have direct bearing on modern life, he said, they do serve as a cautionary tale for those who assume humans are no longer at the mercy of the environment.

“Some of us in the West have a profound belief that no matter what problems we are faced with, we are going to be able to innovate our way out,” he said. “All archaeologists can do is say, ‘Well, perhaps, let’s hope you’re right, but here are many counterexamples where human societies — humans who were very innovative and inventive — were not able to innovate their way out of a major crisis.’”

For all things science, follw me @ScienceJulia.