Expressions of fear and disgust aided human survival, study says

Researchers at Cornell University say the expressions people make when they are scared or disgusted alter their visual perception and may have aided our ancestors’ survival in difficult situations.

- Share via

Why do our eyes open wide when we feel fear or narrow to slits when we express disgust? According to new research, it has to do with survival.

In a paper published Thursday in the journal Psychological Science, researchers concluded that expressions of fear and disgust altered the way human eyes gather and focus light.

They argued that these changes were the result of evolutionary development and were intended to help humans survive, or at least detect, very different threats.

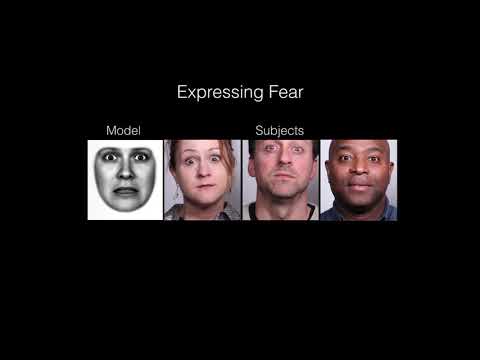

To test their hypothesis, study authors examined two dozen volunteer undergraduate students with standard eye-exam equipment, and asked them to mimic expressions of fear and revulsion.

Researchers found that when the students widened their eyes, their corneas admitted more light and expanded their field of vision. When they wrinkled their noses in disgust, their eyes narrowed. This had the effect of blocking out more light but sharpening focus on a specific point, authors wrote.

Although some scientists have proposed that emotional expressions are intended primarily to communicate information, study authors argued that expressions of fear and disgust seem to perform different visual functions.

“Eye widening may improve detection and localization of a potential threat that requires enhanced vigilance, which would be consistent with the hypothesized function of fear,” wrote senior author Adam Anderson, a professor of human development at Cornell University. (The research was conducted by Anderson and his colleagues at the University of Toronto.)

“Conversely, eye narrowing may improve perceptual discrimination to discern different kinds of threats, such as disease vectors and contaminated foods, avoidance of which is a hypothesized function of disgust,” Anderson and his colleagues wrote.

Study authors said their findings supported the view of naturalist Charles Darwin, who argued that expressions did not necessarily originate for communication and were not arbitrary.

“If our expressions were arbitrary configurations, they would show little cross-cultural correspondence,” authors wrote. “But rather than being a collection of discrete, independent categories, our expressions probably adhere to some underlying universal functional principles.”