How bad could this coronavirus outbreak get?

- Share via

SAN FRANCISCO — There’s no question the coronavirus outbreak is bad, with nearly 90,000 people infected and 3,000 dead in less than three months. What everyone wants to know is how much worse the outbreak will get.

No one can predict the future. But experts who have tangled with infectious diseases for years look to pandemics of the past for hints about what’s to come. Based on what we know now, here’s a sense of what we may face:

How severe could this coronavirus outbreak get?

The 1918 Spanish flu — the worst pandemic of the 20th century — is estimated to have killed at least 50 million people worldwide over the course of three years. That includes 675,000 in the U.S. Among those who were infected, the death rate was estimated to be greater than 2.5%.

The most recent pandemic flu — caused by the H1N1 virus that emerged from pigs in 2009 — caused somewhere between 152,000 and 575,000 deaths around the world. An estimated 12,500 of those fatalities occurred in the U.S. during the first year of the outbreak; an estimated 60.8 million nationwide were infected.

The new coronavirus could wind up somewhere in between, said Dr. Otto Yang, an infectious disease expert at UCLA. Based on what’s known right now, his best guess is that it might resemble the pandemic flu of 1968, which killed about 1 million people globally, including 100,000 in the U.S.

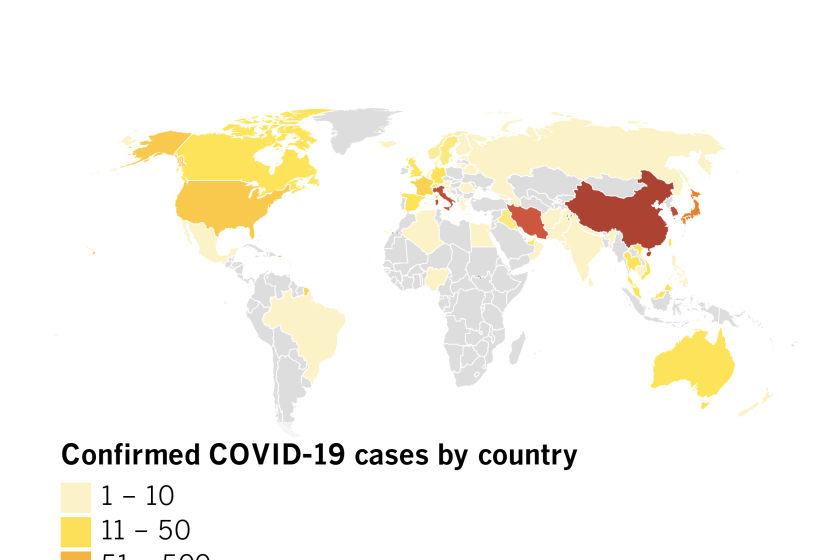

The vast majority of confirmed coronavirus cases — nearly 94% — have occurred in mainland China. But illnesses have been confirmed on all six continents.

Since 2010, the death toll of a single flu season has ranged between 12,000 to 61,000 in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The current flu season, which began in October, has seen about 18,000 deaths so far.

At the moment, it makes sense for officials to focus the public’s attention on preventive measures like washing your hands frequently with soap and water, decontaminating surfaces with a bleach-based wipe, and staying home if you are sick, Yang said.

Soap and water are better than alcohol-based hand sanitizer, he added. While the new coronavirus can be cleaned off of hands by soap and water as well as by alcohol, other viruses can be resistant to alcohol.

Why did conditions in Wuhan get so bad?

Chinese authorities made a big mistake in allowing huge Lunar New Year celebrations to go on even though there were ample warnings that the virus was spreading, Yang said. By then, half of the people who were infected had no direct exposure to the market believed to be the source of the virus.

“A huge number of people all got infected all at the same time,” Yang said.

As a result, hospitals were forced to deny beds to those who were gravely ill.

Just a few days later, the government implemented an unprecedented regional quarantine. Five million people fled Wuhan just before the quarantine was enforced and fanned out across the country.

“So you concentrate a bunch of people so they all get sick, and then you let them all spread out throughout the country,” Yang said. “That was complete incompetence.”

It’s possible that fatalities were particularly bad in China because there are so many smokers there, and their damaged lungs made them more vulnerable to the coronavirus. In China, 52% of men and 3% of women are smokers. By contrast, 16% of men and 12% of women in America smoke.

Smoking is “a risk factor for almost any respiratory infectious disease,” said Dr. James Cherry, an infectious disease specialist at UCLA.

Should we expect something similar in the United States?

Yang doesn’t think so. He said the experience in Wuhan might exaggerate how contagious the coronavirus really is.

The fact that the new coronavirus has been circulating in Washington state for weeks but had gone undetected for so long suggests that there have been more infections than official figures suggest, Cherry said. When those cases are taken into account, the death rate falls.

How does this coronavirus differ from previous viruses?

Two other coronaviruses have fueled outbreaks in the 21st century.

SARS — short for severe acute respiratory syndrome — originated in China’s Guangdong province in 2002 and spread to 29 countries. By the time it was contained in 2003, it had caused 8,096 illnesses and 774 deaths.

The containment of the 2003 SARS outbreak is considered one of the biggest public health victories in recent years. Stopping the new coronavirus, known as COVID-19, will probably be much harder.

MERS — or Middle East respiratory syndrome — began in 2012 and sickened at least 2,494 people in 27 countries. At least 858 people died in that outbreak.

The new coronavirus is different from SARS and MERS in two respects.

First, it spreads more easily in public. In less than three months, it has reached more than 60 countries and territories.

Second, it’s less deadly. In a comprehensive study of 44,672 confirmed coronavirus cases in mainland China, 1,023 people died, researchers from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. That results in a case-fatality rate of 2.3%, the study said.

The death rate due to SARS was about 9.6%, and the fatality rate for MERS is 34.4%.

The actual fatality rate for the new coronavirus may be quite a bit lower than 2.3% because people who are infected but experience only mild illness — or no symptoms at all — are massively undercounted, experts said. The true death rate could be as low as 0.2%, Yang said.

There are four other coronaviruses that produce symptoms no worse than a common cold in most people who do not have severely weakened immune systems, Yang said. These viruses are responsible for 20% to 30% of common colds around the country every year, he said.

There continue to be concerns that visibly healthy people can shed the new coronavirus, which would make the virus more easily transmittable throughout the community.

Lin reported from San Francisco. Times staff writer Soumya Karlamangla in Los Angeles contributed to this report.