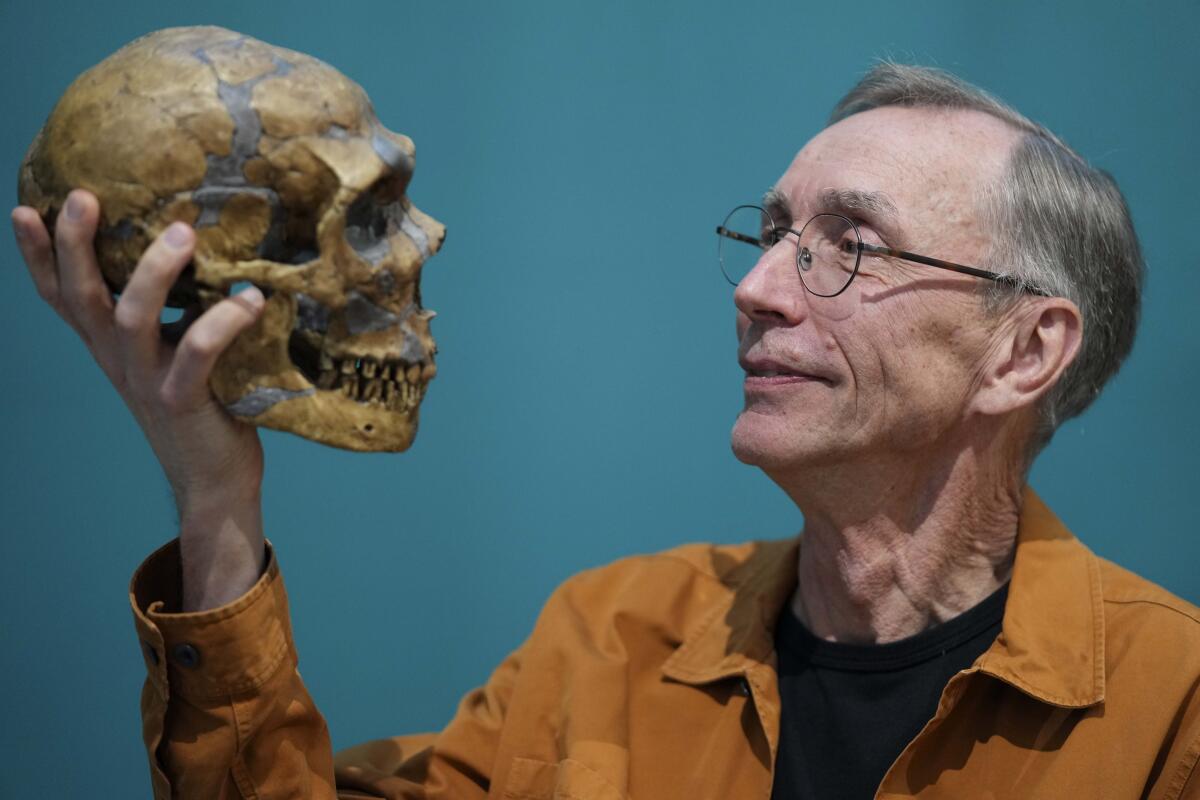

Scientist who decoded Neanderthal DNA wins Nobel Prize for insights on human evolution

- Share via

STOCKHOLM — Swedish scientist Svante Paabo won the Nobel Prize in medicine Monday for unlocking secrets hidden in Neanderthal DNA that helped us understand what makes humans unique compared with our extinct cousins and provided key insights into our modern-day immune systems, including our vulnerability to severe COVID-19.

Techniques that Paabo spearheaded allowed researchers to compare the genome of modern humans and that of other hominins — the Neanderthals as well as the Denisovans.

For the record:

8:13 p.m. Oct. 3, 2022An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel died in 1895. He died in 1896.

“Just as you do an archeological excavation to find out about the past, we sort of make excavations in the human genome,” he said at a news conference held by Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig.

While Neanderthal bones were first discovered in the mid-19th century, only by unlocking their DNA — often referred to as the code of life — have scientists been able to fully understand the links between species.

This included the time when modern humans and Neanderthals diverged as a species, around 800,000 years ago.

“Paabo and his team also surprisingly found that gene flow had occurred from Neanderthals to Homo sapiens, demonstrating that they had children together during periods of co-existence,” said Anna Wedell, chair of the Nobel Committee.

Their mates were real Neanderthals

This transfer of genes between hominin species affects how the immune system of modern humans reacts to infections, including ones caused by the coronavirus. Neanderthals were never in Africa, but people outside the continent have about 1% to 2% of Neanderthal genes.

Paabo and his team also managed to extract DNA from a tiny finger bone found in a cave in Siberia, leading to the recognition of a new species of ancient humans they called Denisovans.

Wedell described this as “a sensational discovery” that subsequently showed Neanderthals and Denisovans to be sister groups which split from each other around 600,000 years ago. Denisovan genes have been found in up to 6% of modern humans in Asia and Southeast Asia, indicating that interbreeding occurred there, too.

“By mixing with them after migrating out of Africa, Homo sapiens picked up sequences that improved their chances to survive in their new environments,” Wedell said. For example, Tibetans share a gene with Denisovans that helps them adapt to the high altitudes.

Genome of ancient Denisovans may help clarify human evolution

Paabo said he was surprised to learn of his win, and at first thought it was an elaborate prank by colleagues or a call about his summer home.

“I was just gulping down the last cup of tea to go and pick up my daughter at her nanny where she has had an overnight stay, and then I got this call from Sweden and I of course thought it had something to do with our little summer house in Sweden,” he said in an interview posted on the Nobel website. “I thought, ‘Oh the lawn mower’s broken down or something.’”

He mused about what would have happened if Neanderthals had survived 40,000 more years.

“Would we see even worse racism against Neanderthals, because they were really in some sense different from us? Or would we actually see our place in the living world quite in a different way when we would have other forms of humans there that are very like us but still different?” he said.

For more than 200,000 years, Neanderthals successfully occupied the cold, dark forests and shores of Europe.

Paabo, 67, performed his prize-winning studies in Germany at the University of Munich and at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig.

After the news conference, colleagues threw Paabo into a pool of water during the celebrations. He took it with humor, splashing his feet a little and laughing.

Scientists in the field lauded the Nobel Committee’s choice.

David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School, said he was thrilled that the group honored the field of ancient DNA, which he worried might “fall between the cracks.”

By recognizing that DNA can be preserved for tens of thousands of years — and developing ways to extract it — Paabo and his team created a completely new way to answer questions about our past, Reich said.

“It’s totally reconfigured our understanding of human variation and human history,” Reich said, adding that Paabo “was, more than anyone, the pioneer of this field.”

The genetic code of the long-dead species could shed light on the evolution of humans, researchers say.

Dr. Eric Green, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute at the U.S. National Institutes of Health, called it “a great day for genomics,” a relatively young field first named in 1987.

The Human Genome project, which ran from 1990-2003, “got us the first sequence of the human genome, and we’ve improved that sequence ever since,” Green said.

When you sequence DNA from an ancient fossil, you only have “vanishingly small amounts,” Green said. Among Paabo’s innovations was figuring out methods for extracting and preserving these tiny amounts. He was then able to lay pieces of the Neanderthal genome sequence against the human sequencing of the Human Genome Project.

Paabo’s team published the first draft of a Neanderthal genome in 2009, and sequenced more than 60% of the full genome from a small sample of bone, after contending with decay and contamination from bacteria.

“We should always be proud of the fact that we sequenced our genome. But the idea that we can go back in time and sequence the genome that doesn’t live anymore and something that’s a direct relative of humans is truly remarkable,” Green said.

Genes that some people have inherited from their Neanderthal ancestors may increase their risk of suffering severe forms of COVID-19, a new study suggests.

Paabo said they discovered during the pandemic that “the greatest risk factor to become severely ill and even die when you’re infected with the virus has come over to modern people from Neanderthals. So we and others are now intensely studying the Neanderthal version versus the protective modern version to try to understand what the functional difference would be.”

Paabo’s father, Sune Bergstrom, won the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1982, making this the eighth time the son or daughter of a laureate has also won a Nobel Prize. In his book “Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes,” Paabo described himself as Bergstrom’s “secret extramarital son” — something he also mentioned briefly at the news conference.

The medicine prize kicks off a week of Nobel Prize announcements. It continues Tuesday with the physics prize, with chemistry Wednesday and literature Thursday. The 2022 Nobel Peace Prize will be announced Friday and the economics award Oct. 10.

Last year’s recipients were California scientists David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian for their discoveries on how the human body perceives temperature and touch.

The prizes carry a cash award of 10 million Swedish kronor (nearly $900,000) and will be handed out Dec. 10. The money comes from a bequest left by the prize’s creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, who died in 1896.