Mosquitoes, long the enemy, are now bred to help prevent the spread of dengue fever

- Share via

TEGUCIGALPA, Honduras — For decades, preventing dengue fever in Honduras has meant teaching people to fear mosquitoes and avoid their bites. Now, Hondurans are being educated about a potentially more effective way to control the disease — and it goes against everything they’ve learned.

That explains why a dozen people cheered last month as Tegucigalpa resident Hector Enriquez held a glass jar filled with mosquitoes above his head, and then freed the buzzing insects into the air. Enriquez, a 52-year-old mason, had volunteered to help publicize a plan to suppress dengue by releasing millions of special mosquitoes in the Honduran capital.

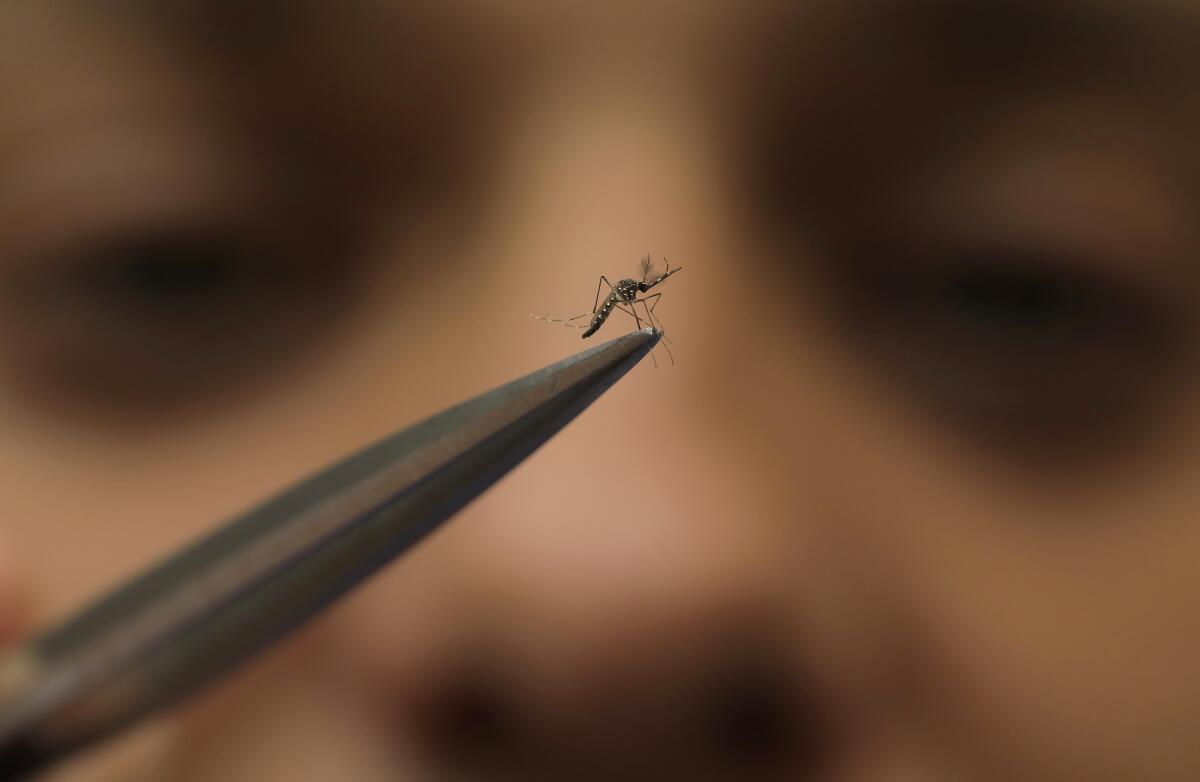

The mosquitoes Enriquez unleashed in his El Manchen neighborhood — an area rife with dengue — were bred by scientists to carry bacteria called Wolbachia that interrupt transmission of the disease. When these mosquitoes reproduce, they pass the bacteria to their offspring, reducing future outbreaks.

This emerging strategy for battling dengue was pioneered over the last decade by the nonprofit World Mosquito Program, and it is being tested in more than a dozen countries. With more than half the world’s population at risk of contracting dengue, the World Health Organization is paying close attention to the mosquito releases in Honduras and elsewhere, and it is poised to promote the strategy globally.

In Honduras, where 10,000 people are known to be sickened by dengue each year, Doctors Without Borders is partnering with the mosquito program over the next six months to release close to 9 million mosquitoes carrying Wolbachia.

“There is a desperate need for new approaches,” said Scott O’Neill, founder of the mosquito program.

Scientists have made great strides in recent decades in reducing the threat of infectious diseases, including mosquito-borne viruses such as malaria. But dengue is the exception: Its rate of infection keeps going up.

Models estimate that around 400 million people across some 130 countries are infected each year with dengue. Mortality rates from dengue are low — an estimated 40,000 people die each year from it — but outbreaks can overwhelm health systems and force many people to miss work or school.

“When you come down with a case of dengue fever, it’s often akin to getting the worst case of influenza you can imagine,” said Conor McMeniman, a mosquito researcher at Johns Hopkins University.

Traditional methods of preventing mosquito-borne illnesses haven’t been nearly as effective against dengue.

Since getting a foothold in L.A. County a decade ago, the aggressive Aedes mosquito has expanded rapidly. It has been found from Laguna Beach to Santa Clarita.

The Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that most commonly spread dengue have been resistant to insecticides, which have fleeting results even in the best-case scenario. And because dengue virus comes in four different forms, it is harder to control through vaccines.

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are also a challenging foe because they’re most likely to bite during the day, so bed nets aren’t much help against them. Because these mosquitoes thrive in warm and wet environments, and in dense cities, climate change and urbanization are expected to make the fight against dengue even harder.

“We need better tools,” said Raman Velayudhan, a researcher from the WHO’s Global Neglected Tropical Diseases Program. “Wolbachia is definitely a long-term, sustainable solution.”

Velayudhan and other experts from the WHO plan to publish a recommendation as early as this month to promote further testing of the Wolbachia strategy in other parts of the world.

The Wolbachia strategy has been decades in the making.

The bacteria exist naturally in about 60% of insect species, just not in the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

“We worked for years on this,” said O’Neill, 61, who with help from his students in Australia figured out how to transfer the bacteria from fruit flies into Aedes aegypti mosquito embryos by using microscopic glass needles.

About 40 years ago, scientists aimed to use Wolbachia in a different way: to drive down mosquito populations. Because male mosquitoes carrying the bacteria only produce offspring with females that also have it, scientists would release infected male mosquitoes into the wild to breed with uninfected females, whose eggs would not hatch.

But along the way, O’Neill’s team made a surprising discovery: Mosquitoes carrying Wolbachia didn’t spread dengue — or other related diseases, including yellow fever, Zika and chikungunya.

And since infected females pass Wolbachia to their offspring, they will eventually “replace” a local mosquito population with one that carries the virus-blocking bacteria.

The replacement strategy has required a major shift in thinking about mosquito control, said Oliver Brady, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

“Everything in the past has been about killing mosquitoes, or at the very least, preventing mosquitoes from biting humans,” Brady said.

A fundamental piece of the Southern California lifestyle is going the way of the Red Cars and the Brown Derby. The freedom to sit outdoors unmolested by bugs.

Since O’Neill’s lab first tested the replacement strategy in Australia in 2011, the World Mosquito Program has run trials affecting 11 million people across 14 countries, including Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Fiji and Vietnam.

The results are promising. In 2019, a large-scale field trial in Indonesia showed a 76% drop in reported dengue cases after Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes were released.

Still, questions remain about whether the replacement strategy will be effective — and cost-effective — on a global scale, O’Neill said. The three-year Tegucigalpa trial will cost $900,000, or roughly $10 per person that Doctors Without Borders expects it to protect.

Scientists aren’t yet sure how Wolbachia actually blocks viral transmission. And it isn’t clear whether the bacteria will work equally well against all strains of the virus, or if some strains might become resistant over time, said Bobby Reiner, a mosquito researcher at the University of Washington.

“It’s certainly not a one-and-done fix, forever guaranteed,” Reiner said.

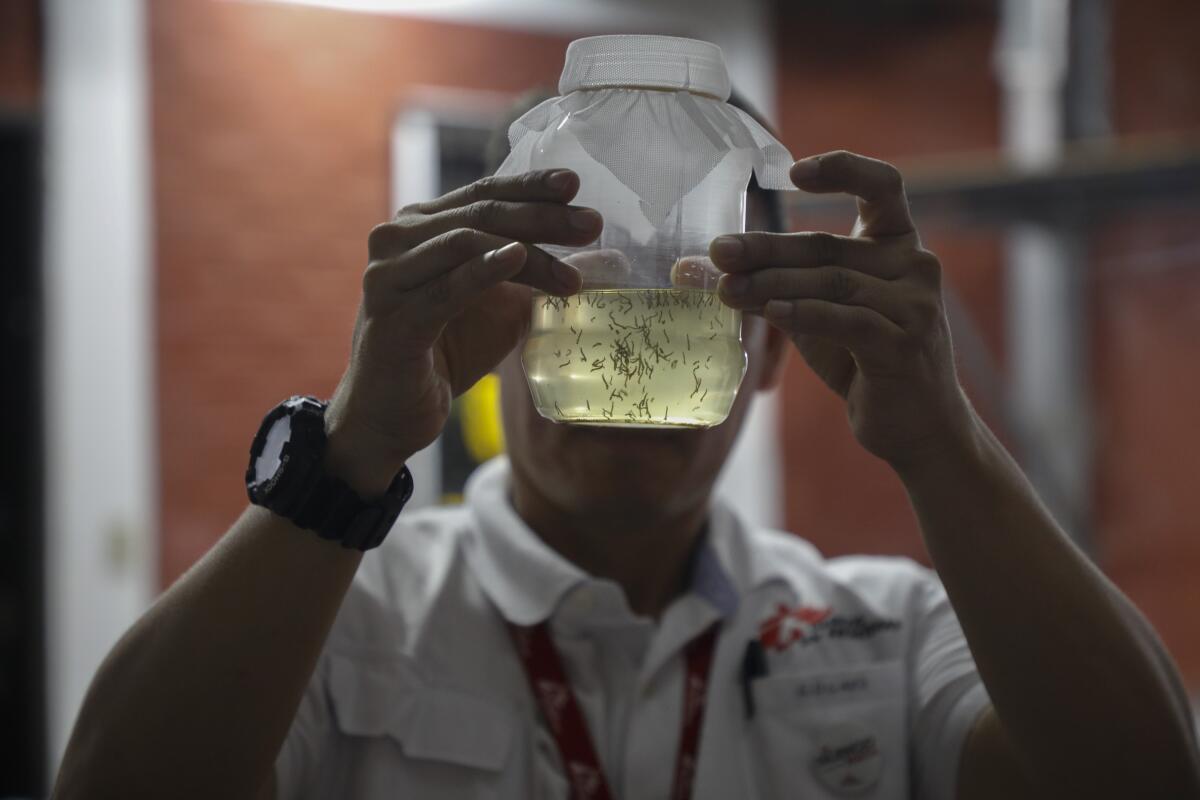

Many of the world’s mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia were hatched in a warehouse in Medellín, Colombia, where the World Mosquito Program runs a factory that breeds 30 million of them per week.

The factory imports dried mosquito eggs from different parts of the world to ensure the specially bred mosquitoes it eventually releases will have similar qualities to local populations, including resistance to insecticides, said Edgard Boquín, one of the Honduras project leaders working for Doctors Without Borders.

The dried eggs are placed in water with powdered food. Once they hatch, they are allowed to breed with the “mother colony” — a lineage that carries Wolbachia and is made up of more females than males.

A constant buzz fills the room where the insects mate in cube-shaped cages made of mosquito nets. Caretakers ensure they have the best diet: Males get sugared water, while females “bite” into pouches of human blood kept at 97 degrees Fahrenheit (37 degrees Celsius).

“We have the perfect conditions,” the factory’s coordinator, Marlene Salazar, said.

As an aggressive mosquito spreads in California, scientists say we got very lucky that the insects couldn’t transmit COVID-19 to people.

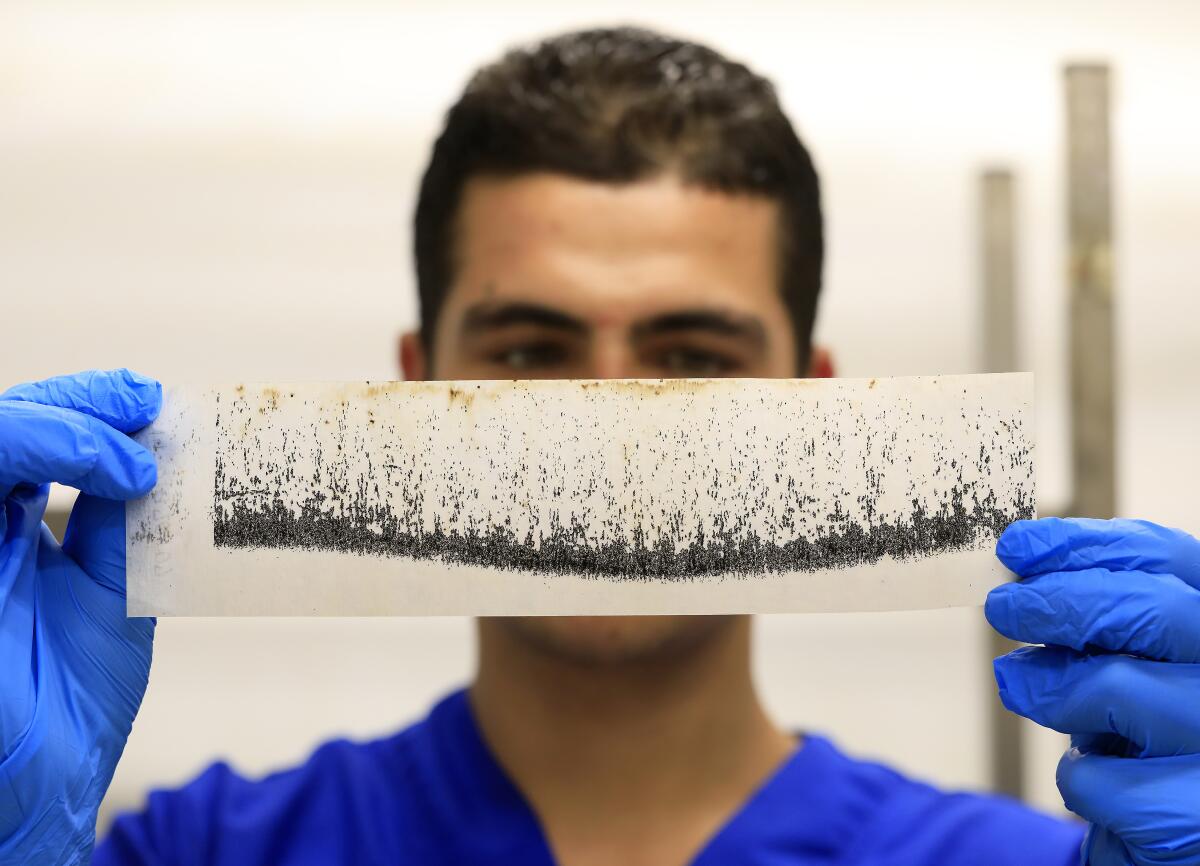

Once workers confirm that the new mosquitoes carry Wolbachia, their eggs are dried and filled into pill-like capsules to be sent off to release sites.

The Doctors Without Borders team in Honduras recently went door to door in a hilly neighborhood of Tegucigalpa to enlist residents’ help in incubating mosquito eggs bred in the Medellin factory.

At half a dozen houses, they received permission to hang from tree branches glass jars containing water and a mosquito egg-filled capsule. After about 10 days, the mosquitoes would hatch and fly off.

That same day, a dozen young workers from Doctors Without Borders fanned out across northern Tegucigalpa on motorcycles carrying jars of the already hatched dengue-fighting mosquitoes and, at designated sites, released thousands of them into the breeze.

Because community engagement is key to the program’s success, doctors and volunteers have spent the last six months educating neighborhood leaders, including influential gang members, to get their permission to work in areas under their control.

Some of the most common questions from the community were about whether Wolbachia would harm people or the environment. Workers explained that any bites from the special mosquitoes or their offspring were harmless.

María Fernanda Marín, a 19-year-old student, works for Doctors Without Borders in a facility where Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes are hatched for eventual release. She proudly shows neighbors a photo of her arm covered in bites to help earn their trust.

Lourdes Betancourt, 63, another volunteer with the Doctors Without Borders team, was at first suspicious of the new strategy. But Betancourt — who has been sickened by dengue several times — now encourages her neighbors to let the “good mosquitoes” grow in their yards.

“I tell people not to be afraid, that this isn’t anything bad, to have trust,” Betancourt said. “They are going to bite you, but you won’t get dengue.”

Burakoff reported from New York City. AP journalist Marko Álvarez contributed to this story from Medellín.