- Share via

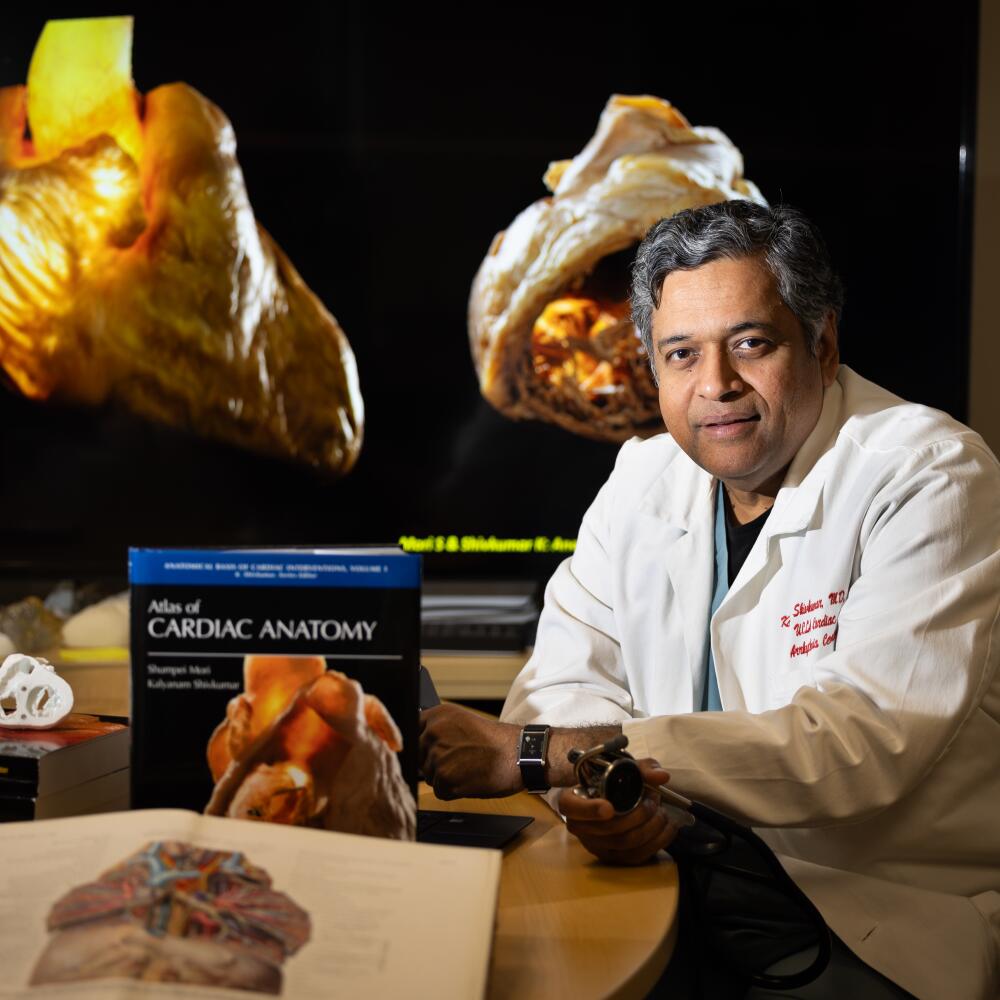

As Dr. Kalyanam Shivkumar pondered how to fix the human heart, he was given a gift laced with horror.

Shivkumar, a cardiac electrophysiologist known as “Shiv” to friends and co-workers at UCLA, was trying to better understand the intricate details of nerves in the chest. He hoped doing so might help him improve treatments for cardiac arrhythmias — aberrant rhythms of the heart — that can prove dangerous and even deadly.

A Canadian colleague sent him a set of anatomy books renowned for the beauty and detail of their drawings, but tipped him off that the “atlas” had an appalling history.

Shivkumar was aghast to learn it was the work of an ardent Nazi whose Vienna institute had dissected the bodies of prisoners, many executed for political reasons after Austria was annexed to Nazi Germany in 1938.

“Every time I open up that book,” he said, “my sense is revulsion.”

Shivkumar is a big thinker, an erudite physician quick with an apt quotation, whose Westwood office is stacked with Sanskrit volumes of the Mahabharata alongside books related to legendary Bruins basketball coach John Wooden.

As he waded into the scholarly debate over using the tainted atlas, the doctor bristled at hearing others praise its illustrations as “unsurpassable.” Much of the soul searching among physicians had revolved around when and how to use it. Shivkumar wanted to put those questions to bed.

“Could we be better?” he asked. “Could we not be making something that’s completely untainted?”

That question would launch Shivkumar on a quest that has lasted more than a decade and is expected to endure for years. He wants to surpass the anatomical atlas created by Dr. Eduard Pernkopf, a fervent supporter of the Nazi regime whose work was fueled by the dead bodies of its victims.

His passion project at the UCLA Cardiac Arrhythmia Center is called Amara Yad, a mashup of Sanskrit and Hebrew meaning “immortal hand.” The work has relied on the generosity of people who have willed their bodies for use at UCLA, as well as hearts that were donated but could not be used for transplant.

So far, Amara Yad has completed two volumes focused on the anatomy of the heart and is enlisting teams at other universities for more. The plan is to draft a freely available, ethically sourced road map to the entire body that eclipses the weathered volumes of watercolors from Pernkopf and honors the Nazis’ victims.

Anatomists have told him, “‘You’re crazy. It’s impossible. How could you ever surpass it?’” Shivkumar said of the Pernkopf atlas in a speech last year before members of the Heart Rhythm Society.

But “can it be beaten? The answer is yes.”

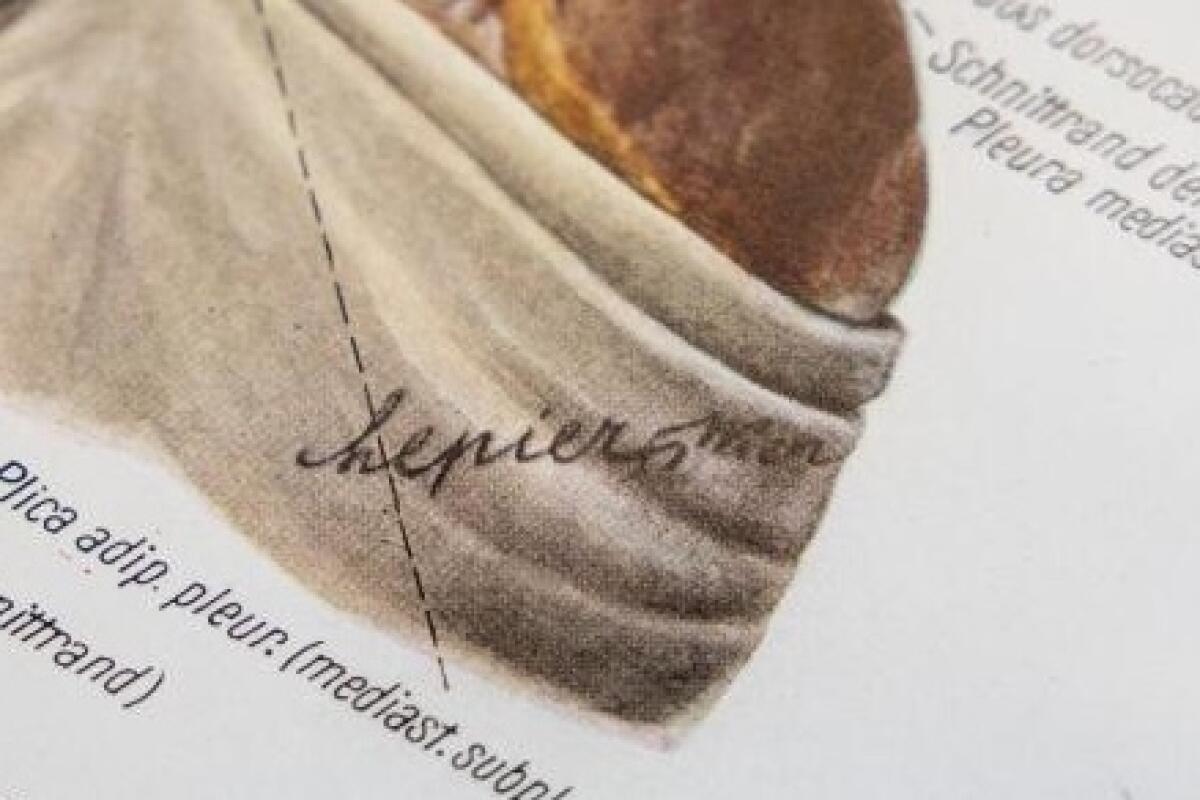

For decades, the origins of the Pernkopf Atlas were unknown to many who turned to its pages for guidance. Swastikas tucked into signatures of an illustrator were airbrushed out in later editions. Its history began to trickle out in journals in the 1980s.

When Dr. Howard Israel finally learned of its roots, he was horrified. Israel, an oral surgeon at Columbia University and self-described “very ordinary American Jew,” told the New York Times he had been relying on the book since he was a medical student.

“I felt stupid at using the book,” he told the newspaper, “that I could possibly have benefited from something that sounded so evil.” He and another physician enlisted the Holocaust remembrance group Yad Vashem and publicly pushed for the University of Vienna to investigate whose bodies were depicted in its pages.

The resulting probe found no evidence that the anatomy department under Pernkopf — who had ascended to become dean of the medical faculty at the University of Vienna in 1938 — had received bodies from the Mauthausen concentration camp, as some had wondered.

But the institute had been given at least 1,377 bodies of executed people, most of them sentenced to death for political reasons. Among the charges that led to their executions: “crimes of resistance” and “high treason.”

Using the bodies of executed people was “a centuries-old practice in anatomy,” preferred because anatomists could time their work swiftly after a scheduled death, said Dr. Sabine Hildebrandt, an anatomy educator at Harvard Medical School. What was new under the Nazis, she said, was the sheer number of executions.

The institute “was drowned in bodies,” and “the source for these bodies was mostly connected with the apparatus of repression of the Nazi regime,” said historian Herwig Czech, a member of the Lancet Commission on Medicine, Nazism, and the Holocaust, at a recent forum.

By the time those findings emerged, the publisher of the anatomy book had stopped printing it.

1

2

1. A stack of volumes of the Pernkopf atlas on a shelf in Dr. Kalyanam Shivkumar’s UCLA office. 2. Erich Lepier, one of the Pernkopf atlas illustrators, repeatedly included a swastika after the cursive R in his signature. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Yet use of the atlas persisted. Hildebrandt said that a decade ago, dental students in her classes “were basically giving each other thumb drives with bootlegged copies of the head and neck.”

Other anatomical atlases exist, but these illustrations had especially fine details, including of the nerves extending beyond the brain and spiral cord. One survey of nerve surgeons found that 13% of respondents were using the atlas. Among those who have publicly grappled with it is Dr. Susan Mackinnon, a surgery professor at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis known as a pioneer in nerve regeneration.

“I used this textbook for years before I knew the history of it,” she said. “My brain is contaminated with that. I can’t undo that.”

Mackinnon sought ethical guidance. Rabbi Joseph Polak, a Boston University assistant adjunct professor of health law who survived the concentration camps as a child, said one dilemma involved a patient in excruciating pain.

A Los Angeles County initiative called Reaching the 95% aims to engage with more people than the fraction of Angelenos already getting addiction treatment.

Polak recalled that the patient had told Mackinnon that “if you can’t find the nerve to stop the pain, then I want my leg amputated.” The rabbi walked through Jewish teachings that applied to the ethical quandary and conferred with other experts, penning a set of recommendations called the Vienna Protocol.

Among his urgings to doctors: If you use these drawings, make it clear to patients where they came from.

The Third Reich wanted “to extinguish them and to extinguish eventually all memory of them,” the rabbi said of Holocaust victims, speaking at a recent forum about the atlas. But when a doctor tells patients about what happened to the people depicted in the drawings, he said, “they’re being called out of that darkness.”

Mackinnon now keeps the atlas locked away. In the rare cases she feels she needs to consult it to operate, she tells patients and co-workers about the man behind it. His firings of Jewish doctors. The grim details in its pages — shorn hair, emaciated bodies — that began to raise suspicions about its terrible origins.

The only reason to use it, she said, is to save someone from misery — and only if “nothing else will help you.”

Shivkumar said his goal is to eliminate the need to consult those pages at all. Inside UCLA’s Center for the Health Sciences in Westwood, he showed off a donated heart, prepped and ready for its close-up in a corner of the lab outfitted with a black backdrop and brilliant lights.

A spent heart normally wilts like a deflated balloon, but this one had been pumped with chemicals to imitate the fullness of life. The team first puts the organs to use in research, then carefully dissects them for imaging.

Bringing out a bisected piece of a heart, Dr. Shumpei Mori displayed how its inner architecture could be captured on camera, threading a catheter through the organ as a co-worker snaked in an endoscope.

“The internal structure is really fine and delicate,” said Mori, a specialist in cardiac anatomy who had jumped at the chance to do something new in the field.

“Even Pernkopf simplified the anatomy” in its drawings, Mori said. “What we are doing is more complicated.”

The camera is far from their only tool: The team has generated 3-D images to illustrate the dimensions of the inner structures of the heart; done CT scans to produce hand-held models; and used sophisticated imaging from a microscope to reveal the lattice of nerves connecting to the organ — part of the signaling system that Shivkumar calls “the internet of the human body.”

In another lab, Mori carefully unzipped a bag on a metal gurney to reveal the stripped-down interior of a cadaver diligently dissected over a year and a half, its rib cage cracked open like a weighty book. Shivkumar pointed out the pale web of nerves stretching up through the neck. Mori had painted them yellow by hand.

The human body might seem like well-traveled territory, but as physicians work to find less invasive ways of healing, such as attacking a cancer with ultrasound, Shivkumar said there is “a volcanic desire for this kind of information.” Snip the right nerve, he said, and you can avert the need for a heart transplant.

“Pernkopf never did nerves like this,” he said with pride.

California lawmakers will introduce a bill to strengthen state law in favor of Holocaust survivors and others seeking to recover looted artwork and other property.

Amara Yad is also an act of “moral repair” meant to honor the victims, said Dr. Barbara Natterson-Horowitz, a UCLA cardiologist and evolutionary biologist who helped support the project. The Nazi atlases “were like documents of death. The atlases that Shiv is creating are really living, interactive tools to support life.”

When Shivkumar decided to launch the project, he had been inspired by the words of USC emeritus professor of rheumatology Dr. Richard Panush, who had pushed to set the atlas aside in the library of the New Jersey medical center where he had worked, moving it to a display case that explained its history.

Panush said the old atlas should be preserved only as “a symbol of what we should not do, and how we should not behave, and the kind of people that we cannot respect.”

Doctors need to know that history to understand their own moral fallibility, Hildebrandt said. Physicians in Nazi Germany “still thought they were doing the right thing,” she said, even as they failed to see some people as human.

Rabbi Polak stressed that doctors at the time “had the deepest, most profound respect of the masses.”

Yet when the Nazis took power, “it turned out that a vast proportion of them were moral sleazeballs,” Polak said. “They were the first to join when they saw that it could promote their careers.”

Shivkumar said that beyond making new tools for physicians, the Amara Yad project is working with Oxford University to develop an accompanying curriculum that will explore ethical failures in medicine. Pernkopf’s anatomy book is only one example.

The history of the atlas “invites the contemplation of how doctors and medical scientists and anatomists are related to a regime,” said Sari J. Siegel, who heads the Center for Medicine, Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Cedars-Sinai. Thinking about it underscores that “medicine is political.”

“It can’t be divorced from the larger contexts in which it exists.”

Shivkumar, born to a Hindu family in the southernmost state of India, is used to people wondering why he became “possessed” with this project. He recalls first learning about the Holocaust from a photographer friend of his grandfather, a former newspaper editor once imprisoned for sedition against the British Empire.

He was 11 when the photographer showed him images dating to World War II, and it chilled him “to see that human beings could be so brutal to other humans.” As a child, his parents had told him they owed the world because their part of India was lucky to be long spared from such conflict.

In Amara Yad, we “get a rare opportunity in history to correct an unbelievably depressing stain that was placed in our field,” he told the Heart Rhythm Society.

It irritates him to think of the abundant resources that a Nazi had at hand to do this sort of work. “Imagine having five Shumpeis!” he exclaimed at one point, gesturing at his colleague who hand painted the nerves. At UCLA, the project has piggybacked on ongoing research and relied on donations. He is hoping to garner $500,000 annually to continue and expand the work.

But Shivkumar likes to quote the Emperor Ashoka on that point: “To do good is difficult. One who does good first does something hard to do. ... Truly, it is easy to do evil.”

In California, doctors trained as pediatricians, OB-GYNs and other specialties can take on lucrative — and potentially risky — cosmetic surgeries. Some have branched out with little or no surgical training.