Orange County keeps focus on housing and services in battle against homelessness

- Share via

Advocates for the unhoused and some lawmakers in Orange County say communities can’t arrest their way out of the homelessness crisis, even after a U.S. Supreme Court decision last month gave municipalities more authority to clear out encampments and an order from California’s governor encouraged them to do so.

In a decision published June 28, the Supreme Court sided with the city of Grant’s Pass, Ore., ruling local governments are allowed to enforce anti-camping laws and remove people from makeshift homes set up on public property whether or not shelter beds are available.

For the record:

3:55 p.m. Aug. 5, 2024An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court was a grand jury report.

The decision has been interpreted as a reversal of a 2018 ruling in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which previously held that clearing out encampments and then citing people forced to vacate without providing some alternative place to stay amounted to cruel and unusual punishment.

Then, on July 25, Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an executive order encouraging, but not requiring, local governments to “prioritize efforts to address encampments.” Among its guidelines, the order instructs state, county and city authorities to:

- identify campsites posing an imminent threat to health, safety or infrastructure;

- provide 48 hours notice to people living there if possible;

- involve caseworkers in the cleanup process to try and connect people with emergency housing and other services;

- store displaced people’s belongings for up to 60 days

Those directions are mostly consistent with the way authorities in Orange County already respond to large encampments of homeless people, county Supervisor Katrina Foley told the Daily Pilot during an interview Wednesday.

Foley said the executive order may help prevent people who are forced to leave encampments near Caltrans-owned freeways or railroad tracks from simply crossing a fence to set up tents on state property. But it’s unlikely to result in dramatic changes to local policy.

“I don’t think it’s going to make a difference, honestly,” the supervisor said of Newsom’s order. “We’re going to do the same thing we’ve been doing, which is send out caseworkers, send out social workers, try to get people into shelter, into recuperative care, reconnected with family members, all of the things we’re doing to get people under a roof.”

She added that the county, Costa Mesa, Anaheim and city of Orange are still bound to the terms of a settlement from a separate case decided in favor of the nonprofit Orange County Catholic Worker in 2018. That ruling by Judge David O. Carter halted the mass displacement and citation of people living in sprawling tent communities along the Santa Ana Riverbed in the absence of adequate shelter.

It also pushed local governments to create more supportive housing and expand services, largely guiding the development of Orange County’s method toward fighting homelessness, said Foley and Brooke Weitzman, an attorney who represented the plaintiff in that case.

“The O.C. cities know better because they’ve tried,” Weitzman said. “They’ve tried to arrest their way out of the problem. They’ve had examples of others doing the wrong thing and have seen that it doesn’t work.”

Focus remains on housing and services

Newport Beach implemented an anti-camping ordinance last summer. And although officials are not aware of any large encampments in the city, their new law has been effective in reducing the number of people seen camping in public, Newport Beach spokesman John Pope said.

“I think it’s worked because we’ve put a lot into support services, in place well prior to the Supreme Court decision,” Pope said. “As a product of Martin v. Boise, years ago cities really had to step up in terms of services.”

The city has an arrangement with the Costa Mesa Bridge Shelter, reserving 25 beds for people living on the street in Newport Beach. It has also contracted with Be Well to run a mobile mental health and wellness team that conducts outreach to homeless people.

The Newport Beach City Council is considering whether any changes to its anti-camping ordinance might be necessary, in light of recent events. Representatives of Fountain Valley said they are also reviewing that city’s policies and procedures regarding encampments.

“It really wasn’t the governor’s office that had influence on Newport Beach’s actions,” Pope said. “It was really the Grant’s Pass decision.”

Securing a place to stay for people displaced from campsites will remain a “top priority” for officials in Huntington Beach, spokeswoman Jessica Cuchilla said. But the availability of shelter in the city has been tight, with the 174-bed Navigation Center run by Mercy House near Beach Boulevard and Slater Avenue at 92% capacity as of late July.

Meanwhile, in response to the governor’s order, Huntington Beach expressed criticism toward the state’s leadership. The conservative majority sitting on its City Council issued a statement accusing lawmakers in Sacramento of a “lack of seriousness toward enforcing existing laws and cleaning up communities.

“In spite of the state’s heavy and wasteful spend of taxpayer dollars, and with the state’s laxed approach to enforcing the state’s existing laws, homelessness has only grown over the years under Gov. Newsom,” the Huntington Beach officials said in their statement.

Crisis continues to outpace solutions

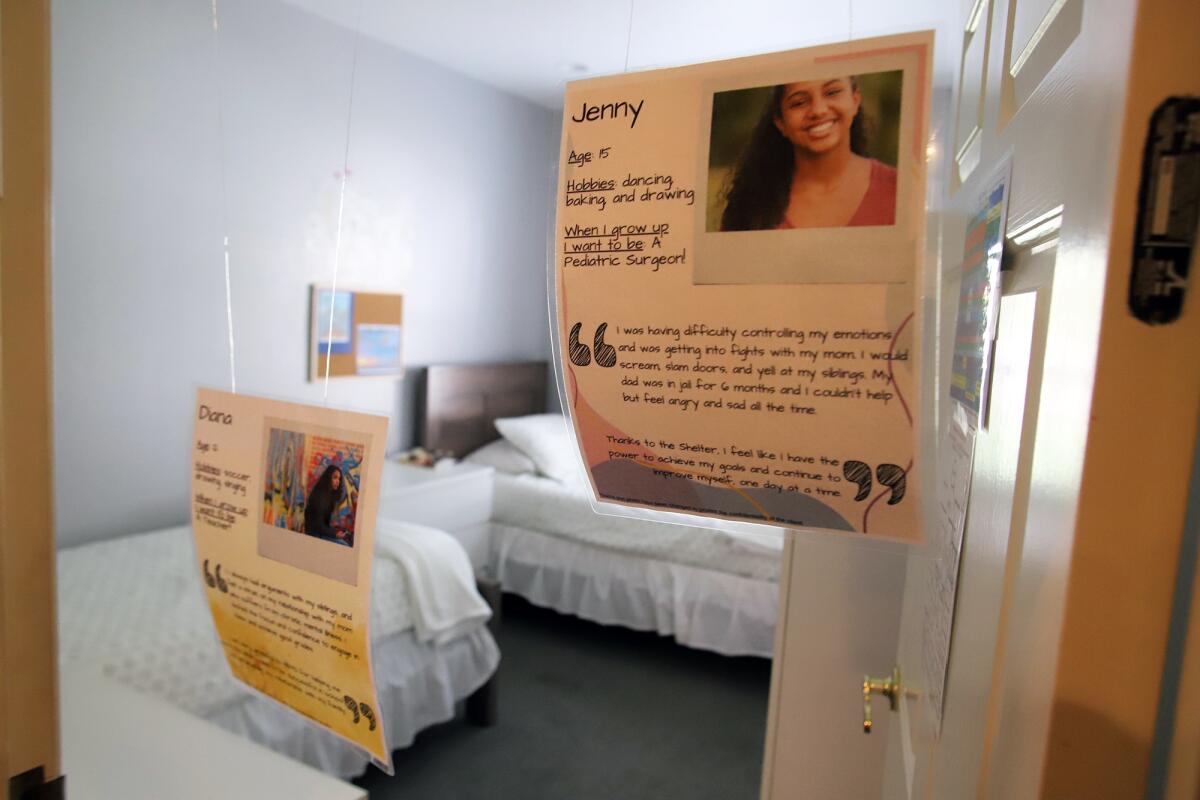

Homelessness remains a highly visible issue in many Southern California communities. And, according to recent data, seniors, veterans and transitional-age youth roughly between the ages of 18 and 24 represent a growing portion of the unhoused population. But that doesn’t mean the strategy of prioritizing housing and services adopted in Orange County and elsewhere hasn’t been working, according to Weitzman.

“Governments, at least locally, have seen a lot of these programs’ success,” she said. “… But we’re also at a moment where we’re seeing really unprecedented numbers of people losing their housing, especially older adults with disabilities, with the cost of housing continuing to skyrocket with limited protections.”

Weitzman said that since 2018, local governments and organizations have become far more efficient at coordinating the web of support programs available to people experiencing homelessness. Applications for supportive housing that used to take five to 10 years to sort out can now be processed in one or two. She pointed to Project Homekey and its followup, Project Home Safe, as examples of agencies effectively collaborating to rapidly get a large number of people off the street and into housing.

“Cities and counties are saying, ‘We’ve done all this work, we’ve gotten all these people into housing,’ and then residents are saying, ‘Why are there more people outside?’” Weitzman said. “And the answer is because they’re different people. Because there are more people outside. That doesn’t negate that, had these governments not done all the work they had done to create all these pathways to housing, there would be even more people outside.”

Encampment residents may still be protected

Although the Grant’s Pass decision upends the Martin vs. Boise ruling, people living in encampments still have some potential legal recourse against sweeps, according to Weitzman. For example, the 4th Amendment’s protection against unlawful search and seizure as well as elements of the Americans with Disabilities Act are part of the basis of lawsuits her office has filed in the San Bernardino County.

“I don’t read it as an open season to arrest every one,” Weitzman said. “And the truth is, many counties have tried that and it doesn’t work. If that’s what it said, there simply isn’t space in jail to arrest all the people living on the street.”

Billions spent on shelter, services and sweeps

Newsom’s order claims his administration has invested roughly $24 billion to address homelessness across the state. That includes $3.3 billion poured into Project Homekey. Since 2021, at least $60 million in Homekey funding has been awarded for supportive housing projects in Orange County.

The state has also spent $1 billion to fund California’s Encampment Resolution Funding, a program local governments can apply for to cover projects related to the relocation and sheltering of people living in encampments. No individual city in Orange County has received ERF money, but in 2022 the county was awarded $3.6 million from the program to relocate about 60 people who had set up a makeshift community in Talbert Park along the Santa Ana River between Costa Mesa and Huntington Beach.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.