Commentary: COVID-19 may redefine society as past crises have

My favorite line from the popular television show “Downton Abbey” was delivered by the incomparable Maggie Smith in the first episode.

When the unexpected new heir to the estate, a young lawyer, said he planned to continue working and would fulfill his earl-in-waiting duties on the weekend, Smith’s character looked confused.

“Weekend?” she said. “What is a weekend?”

That fictional scene was set in 1912, in a time and place far removed from life today. It’s obvious that the line was meant to elicit a laugh, the humor deriving from an aristocratic dowager’s cluelessness about a concept we take for granted.

But it also cleverly underscored another reality that was at the heart of the award-winning series: Things change, people resist, yet eventually we all get swept along anyway.

It’s a thought worth remembering, given our current circumstances. Most of us tend to default to operating as if the way the world works will continue on indefinitely, and then our brains must play catch-up to the forces of change as they propel us into unfamiliar territory.

So it has been throughout history.

In the earliest days of human civilization, what we know as “work” was essentially subsistence living. People performed simple but arduous tasks centered around survival — seeking food, caring for children, finding shelter.

More complex societies were enabled by the development of everything from pottery and textiles, to metal tools and weapons. Over time, larger, more organized work environments, specialization, public works projects and new technologies fueled the transition from an agrarian society to industrialization.

The emergence of the factory system, the managerial class, banking — all these instigated large-scale movement in the manner and places in which people worked. In more recent decades, we’ve seen the transition to a service-based economy, fueled by the growth and increasing sophistication of computers, robotics and, more recently, wireless communications and artificial intelligence.

Sometimes, a shock to the system forces more sudden changes, as was the case when women moved into the workforce in massive numbers during World War II.

Past pandemics provide another case in point, one that’s highly relevant now.

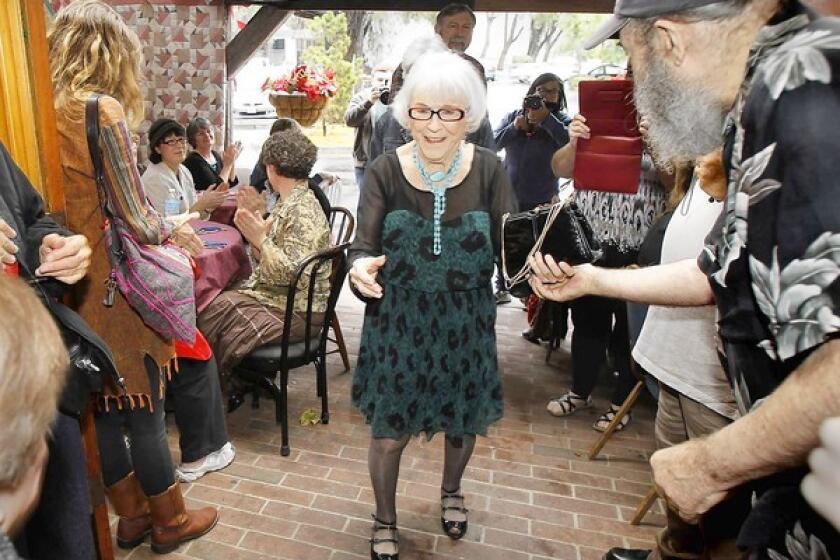

Viola Smith, a Costa Mesa resident and pioneering musician of the swing era who was billed in the 1930s as the “fastest girl drummer in the world,” has died. She was 107.

The Black Death in the 14th century, the deadliest recorded plague in human history, wiped out a huge share of the world population, as many as 200 million people by some estimates. But an unexpected side effect of that devastation was that many serfs were freed, wages for laborers rose and living standards for the survivors began to rise.

The 1918 flu epidemic also generated profound changes. The virus hit young men particularly hard, which together with the effects of World War I, resulted in a labor shortage so severe that entire sectors of the economy were brought to a near standstill.

Into the gap came many women, taking jobs that were previously held only by men. Notably, this occurred at the same time that women were mobilizing to advocate for more rights; two years later, women secured the right to vote in the U.S.

It now appears that we are at another pivotal point at which the very nature of work could be taking a sharp and irrevocable turn.

I’m not suggesting that everything we’re going through now due to the COVID-19 pandemic will stick. Eventually, retail stores and restaurants — those that survive — will return to something approaching normal levels of operations, theaters and theme parks will reopen, many employees who have been laboring at home will go back to communal workplaces, and most of us will resume our usual underappreciation of essential workers.

But it’s also likely that some aspects of the working world will emerge from the pandemic fundamentally altered.

How altered, and in what ways, remains to be seen.

I spoke with UC Irvine sociology professor Judith Stepan-Norris, an authority on workforce issues, about what sort of lasting effects might come out of the pandemic.

On the one hand, some innovative ideas about how to work more efficiently could get some traction, she said. Emerging technologies like virtual reality might get a boost, and we could see a heightened interest in reimagining transportation systems, office and retail design, and business networks.

“The experience that everyone is having is going to shift their thinking,” she believes.

But Stepan-Norris is also concerned that women might come out on the short end this time around.

About 35 adults between the ages of 18 to 55 will be tested as part of the first phase of the hAd5-COVID-19 clinical trial. This is the first COVID vaccine trial at Hoag.

“There have been a lot more women that have dropped out of the workplace” this year, she said. In large measure that’s because we haven’t resolved the issue of child care, and that failure disproportionately affects women.

We’ve also seen the pandemic hit minorities and workers on the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum particularly hard, she noted.

“All those things would argue for greater inequality coming out of this pandemic.”

I’ll add my own prediction about that. Those historically disenfranchised groups won’t sit quietly on the losing end but will use their collective power to push forward their struggle for equity. Perhaps we’ll see a burst of entrepreneurship by women and minorities play a significant role in a recovering employment market.

And a final thought. COVID could hasten the long-anticipated demise of the five-day workweek. Indeed, future generations might find themselves puzzling over exactly what the old-timers mean when they refer to a certain relic of times past, the one they so quaintly called a “weekend.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.