Apodaca: Elon Musk isn’t always right. Take for, for example, his attitude toward remote work

- Share via

In my long career as a journalist I’ve interviewed and written about a lot of very successful people. And on occasion I’ve been struck by one glaring character flaw.

Sometimes people who achieve great success in one thing, or even multiple things, fall into the trap of thinking they’re geniuses at everything. They’ve got it all figured out, they know how to solve every problem and they’re always right.

This isn’t the case with everyone. Many stars — whatever field they happen to be in — remain humble and cognizant that their achievements resulted from multiple factors, including luck, timing and the contributions of others. They seek input from those who know more than they do about particular subjects, and they listen even when the conclusions run counter to their instincts.

But every now and then we are treated to an example of a very smart person sounding very dumb.

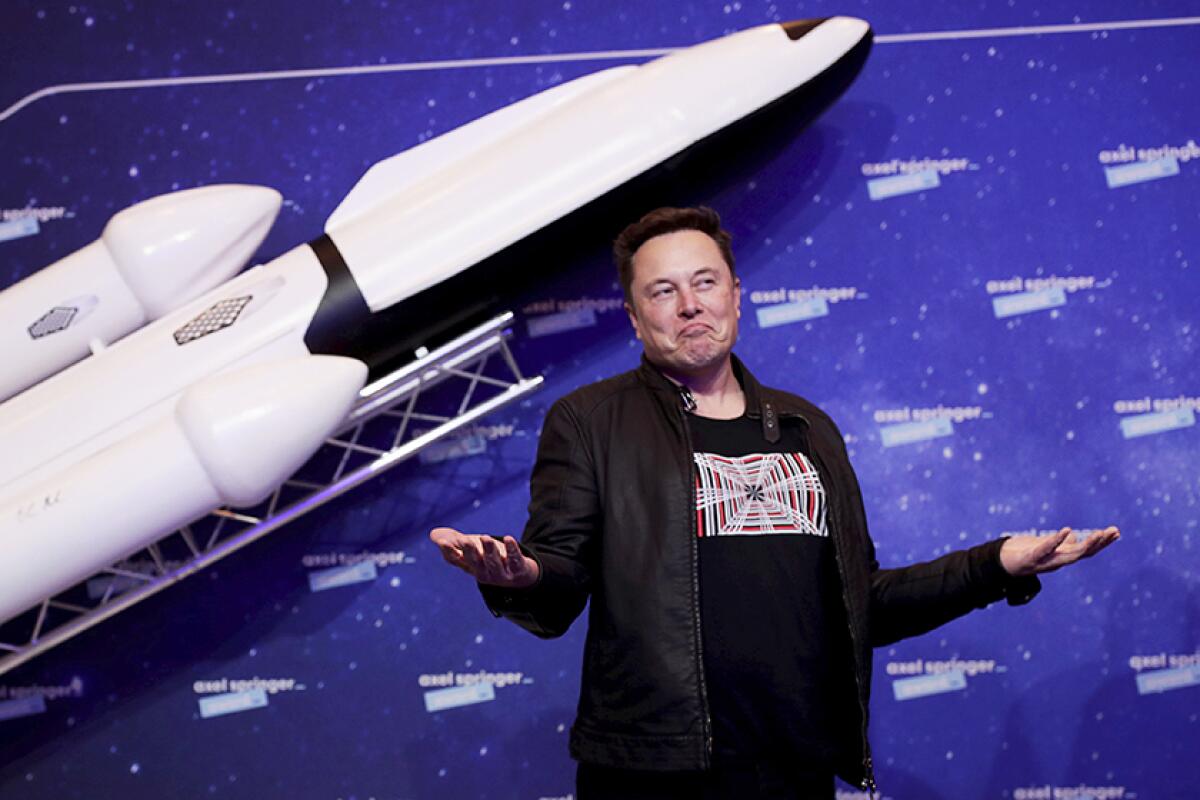

That was my first thought when I heard about Elon Musk’s memos to Tesla and SpaceX employees directing them to return full time to the office or else forfeit their jobs.

Musk wrote, “Anyone who wishes to do remote work must be in the office for a minimum (and I mean *minimum*) of 40 hours per week” or else leave the companies.

In an email Musk made clear his views on the value of remote work by stating, “The office must be where your actual colleagues are located, not some remote pseudo office.” And on Twitter he doubled down on that thought with a gem suggesting that anyone who doesn’t conform to the new policy “should pretend to work somewhere else.”

Musk, of course, is free to run his companies as he sees fit. And he has so far displayed remarkable talent and vision in transforming the electric vehicle and space exploration industries, so naturally many other talented people are drawn to work for him and will be willing to follow his in-person-or-else policy.

He also has plenty of company in placing a high value on physical workplaces.

The problem is that his dictate is so absolute — absent any thoughtfulness, nuance or willingness to acknowledge other viewpoints or complicating factors — that he comes off sounding like a 6-year-old stamping his feet until he gets his toy back.

He might have done better if he had sought the advice of someone like Ian Williamson, the dean of the Paul Merage School of Business at UC Irvine.

Williamson is also a really smart guy. Here’s just a sampling of his background from the UCI website:

“Williamson is a globally recognized expert in the area of human resource management. His research examines the impact of ‘talent pipelines’ on organizational and community outcomes. Williamson has assisted executives in over 20 countries across six continents enhance firm operational and financial outcomes, improve talent recruitment and retention, enhance firm innovation and understand the impact of social issues on firm outcomes.”

So I asked Williamson myself.

As I expected when I questioned him about remote work, the picture is more complex than the binary, all-or-nothing scenario that Musk’s policy suggests.

A Daily Pilot columnist ponders the easy availability of military-style weapons in America and our inability to stem the commonality of mass shootings in our country.

Rather than looking at the issue from a standpoint of remote versus in-person, Williamson sees it more as one of workers seeking greater flexibility and mobility.

This trend has been enabled by technological advancements and the national economy’s shift toward services and away from manufacturing and agriculture. It was developing even before COVID-19 forced many workers into virtual work environments, but the pandemic acted as “an accelerant” of the trend, Williamson said.

“Now this has become embedded,” he said. “It’s not going back in some respects. People are doing work [remotely] and not having negative outcomes in terms of performance. It will be more a part of the repertoire of what companies do.”

The research so far doesn’t necessarily show that one style of work is better than another. Again, it’s more complicated than an either-or scenario. Rather, remote work lends itself toward certain interactions, tasks and types of employees.

For example, Williamson said, face-to-face interactions tend to favor people who are more extroverted and assertive. A positive aspect of virtual work that’s increasingly recognized is that people who are less apt to speak up or be acknowledged in an in-person setting are now more comfortable, and their ideas are getting more attention. Organizations benefit from this diverse input.

What’s needed now, he suggested, is leadership that doesn’t cling too tightly to what’s gone before, but instead facilitates different perspectives, evolving work styles and flexible organizational structures. Many companies will find the best answer will be some blend of in-person and virtual work.

“We all have an opportunity to learn here,” Williamson said. “Those that wait will likely lose out on talent. They lose on productivity.”

One more observation of my own: While Musk isn’t the only employer who prefers to have workers in the office full time, his directive is singular in revealing a breathtaking lack of trust and respect. His failure to acknowledge the hard work and contributions of some of the people who helped him achieve his dazzling success — well, that might be the dumbest part of this whole business.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.