Pilgrimage to an ugly past at Manzanar

The students huddled together, trying to keep warm amid low temperatures and heavy gusts of wind.

More than 250 miles from their homes in sunny Orange County, the harsh climate of Manzanar, which sits at the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada more than 4,000 feet above sea level, was another reminder of the struggles their ancestors endured seven decades ago.

The 15 middle and high school students were musicians with Daion Taiko, a traditional Japanese drumming group affiliated with the Orange County Buddhist Church. They had been invited to perform at the 47th annual Manzanar pilgrimage, where 1,000 people gathered on April 30 to commemorate the 10,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans interned there during World War II.

“They were like penguins, all packed together,” Daryl Doami, managing director of Daion Taiko, said of the students. “From that perspective, they got some experience of the harshness of having to live out there.”

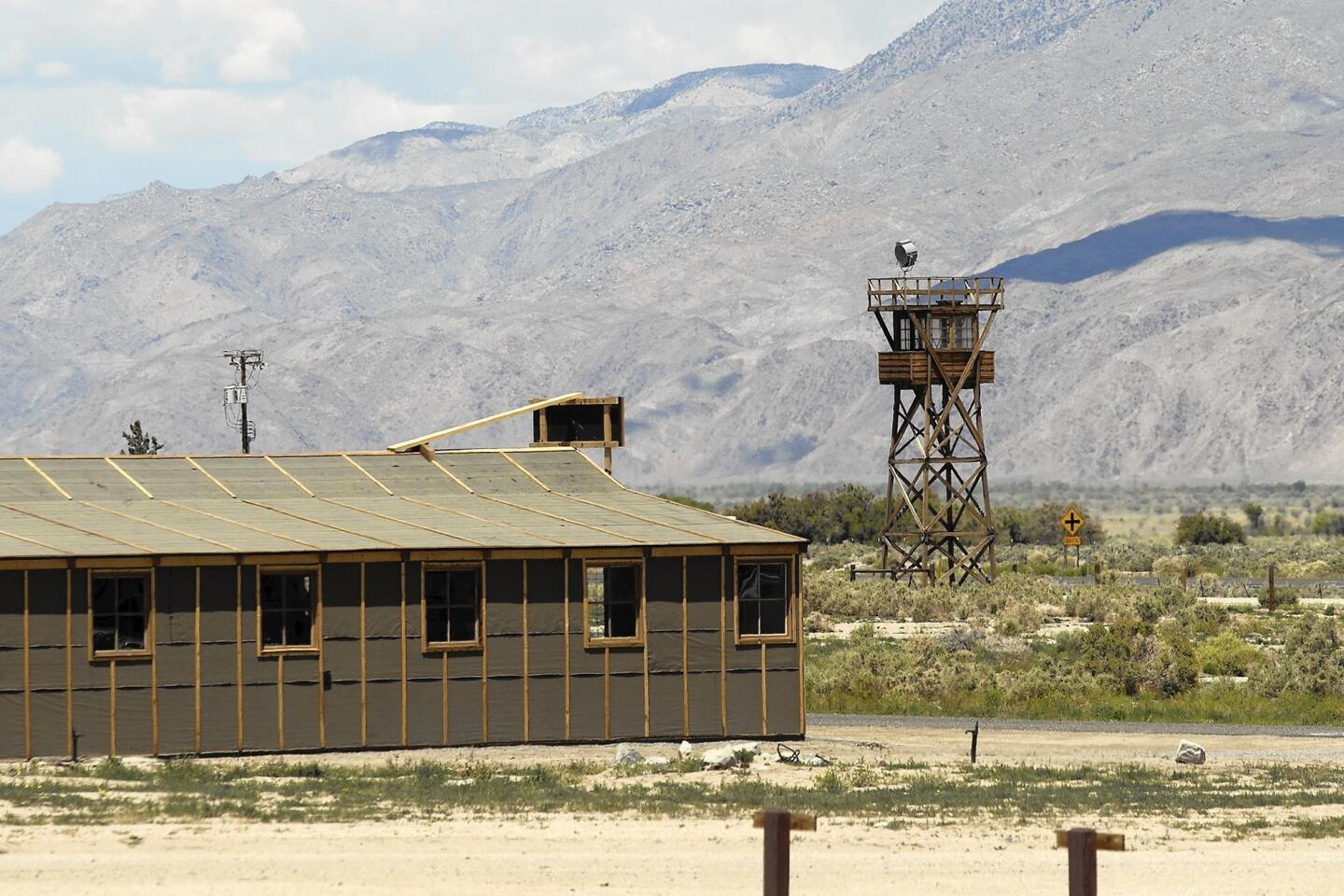

Although the Manzanar National Historic Site offers dramatic views of snow-capped mountains, the desert environment means summers exceeding 100 degrees, winters below freezing and high winds year-round. And for Japanese American families interned there between 1942 and 1945, the small wood-and-tar-paper barracks that they were forced to live in provided little relief.

This is what Doami, whose family was held at Topaz Internment Camp in Utah, was hoping the young musicians of Daion Taiko would take away from the Manzanar pilgrimage — a firsthand taste of what their grandparents and great-grandparents faced while behind barbed wire.

Gianna Furumoto, a senior at Canyon High School in Anaheim, had grown up hearing about Manzanar in school and from family and friends, but agreed that traveling to the site with Daion Taiko deepened her understanding of this part of the country’s history — and gave her a new perspective on her own life.

------------------

FOR THE RECORD

May 23, 7:05 p.m.: An earlier version of this article misspelled the surname of one of the pilgrimage participants. She is Gianna Furumoto, not Surumoto.

-------------------

“You can’t take anything for granted,” she said after the pilgrimage, her first time visiting the internment site. “They were taken out of their own homes and put into a strange place by their own government, so I think it’s important to appreciate everything we have now.”

In February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the forced removal of 120,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants from their homes in California, Washington, Oregon and Arizona to internment camps throughout the country.

Manzanar, which held 10,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans, was one of 10 such camps.

While typically thought of as a response to the December 1941 attacks on Pearl Harbor, historian Greg Robinson, author of “By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans,” explained that internment was many years in the making.

“The government was investigating them and building camps for enemy aliens even before Pearl Harbor,” he said. “There was a long history of discrimination against Japanese Americans, which created momentum for action after the war had begun.”

In the camps, internees were held behind barbed wire, entire families living in rooms just 20 by 20 feet, according to Robinson. Adults were put to work and earned $16 to $19 per month.

One feature that set Manzanar apart from the other internment camps was its Children’s Village, which held 101 orphans and foster children, most under the age of 7.

“The Army was so prejudiced that they removed Japanese American orphans — or orphans who looked like they might have Japanese ancestry — because of the threat they might pose because of their Japanese blood,” Robinson said.

Remembrance of these orphans was the centerpiece of this year’s pilgrimage, whose official theme was “Kodomo No Tame Ni: For the Sake of the Children — Liberty and Justice for All.”

The iconic cemetery monument, or “soul consoling tower” is shown days after the 47th annual pilgrimage at the Manzanar Historical WWII Internment Camp. Mount Williamson is in the background.

After the war ended in 1945, Japanese and Japanese Americans were allowed to return home to the West Coast, but often there was nothing to return to. Many had lost their houses and businesses during internment, while laws prevented them from acquiring property, professional licenses and, if they were immigrants, citizenship. In addition, discrimination — and violence — continued against the community.

“They had been stigmatized by their imprisonment, were desperately short of money because they lost everything, so most of the Japanese immigrants who had been independent farmers or businessmen were forced to go back and become gardeners or menial laborers,” Robinson said. “The young American-born Japanese were able to get education and become middle-class in the years after the war, but there was long-term psychological effects, such as epidemic drug use and family breakdown.”

In 1969, at the height of the Asian American Movement — during which Americans of Asian descent organized to fight against their oppression — students and activists from Southern California organized 200 people to make the first-ever pilgrimage to Manzanar.

“Everyone was marching somewhere, and we wanted to as well,” Bruce Embrey, who lives in the Los Angeles area, recalled his mother, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, saying of the first trek, which she attended.

But the Japanese American community didn’t immediately embrace the idea.

“People were scared, nervous and open about why they didn’t want this talked about,” said Embrey, co-chair of the Manzanar Committee, which sponsors the pilgrimage. “People told my mother directly, to her face, ‘This is going to get them angry and we will suffer again. You’re creating problems for us.’

“It wasn’t just that we got carted off and locked behind barbed wire for a few years,” he explained. “There had been a systematic, legal campaign to prevent Japanese and Japanese Americans from getting established in this country. Those fears and experiences were still fresh on people’s minds.”

Karyl Matsumoto of South San Francisco, who was just 3 months old when she was taken to Manzanar, said this hesitation to talk about internment lasted for many years.

“They considered it a shame,” she said of the older generation. “It was a dark period in their life that they didn’t want to go back to.”

Still, the pilgrimage continued ever year and activists — led by Kunitomi Embrey — successfully lobbied the California government to designate Manzanar a state landmark in 1972. Decades later, it achieved status as a National Historic Site operated by the National Park Service.

Today visitors can tour a 5,000 square-foot museum, reconstructed barracks and mess hall, excavated Japanese gardens and ponds, and cemetery monument.

But perhaps the biggest victory for Japanese Americans was the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which offered a formal apology for the internment, an acknowledgment of its injustice and reparations for living survivors, a move Embrey said lifted a “huge psychological burden” from the community.

These achievements helped change the perception of the Manzanar pilgrimage so that today, about 1,000 attend each year, and similar pilgrimages have been established at other former internment camps, such as Tule Lake in Northern California and Heart Mountain in Wyoming.

“Finally my generation, the baby boomers, has been able to come out of the woodwork and feel more cultural pride,” said Huntington Beach resident Chris Terada, whose mother and two older sisters were interned at Manzanar. She and her family have been making the pilgrimage to Manzanar for the past 15 years. Her sister, Pat Sakamoto, was born there and is a member of the Manzanar Committee.

“I feel glad that my kids now don’t have the feeling of being hidden,” Terada said. “When we go to Manzanar, they can see where they came from and feel proud of who they are.”

This year Terada’s son Tyler, a seventh-grader at Mesa View Middle School, traveled to Manzanar with Daion Taiko. And he didn’t just have to imagine what his family’s life was like in the internment camps; Tyler saw historic photographs of his grandmother and aunts featured in one of the exhibits.

He was also struck by the Children’s Village.

“It’s really different from how we grow up now,” he said. “They obviously had no electronics, they didn’t have any friends of other races, and there were a lot of things they couldn’t do that we do today.

“It helps me appreciate the life we have now, because back then people weren’t so fortunate.”

Even though the Manzanar internment camp closed more than six decades ago, Embrey insists its history is still relevant — particularly today, with growing Islamophobia and calls to ban Muslims from the United States in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in San Bernardino and Paris.

“We have a unique responsibility given the position we’re in to speak out against this climate and label it for what it really is, a racist, semi-hysterical response,” Embrey said. “On one level we may have won an apology and recognition that the forced removal of Japanese Americans was a racist, needless, senseless act, but it didn’t prevent others from now saying, ‘Let’s do it again to the Muslims.’ ”