Dodgers in the Valley? Ballpark might have replaced mall — had the Angels not squashed the idea

- Share via

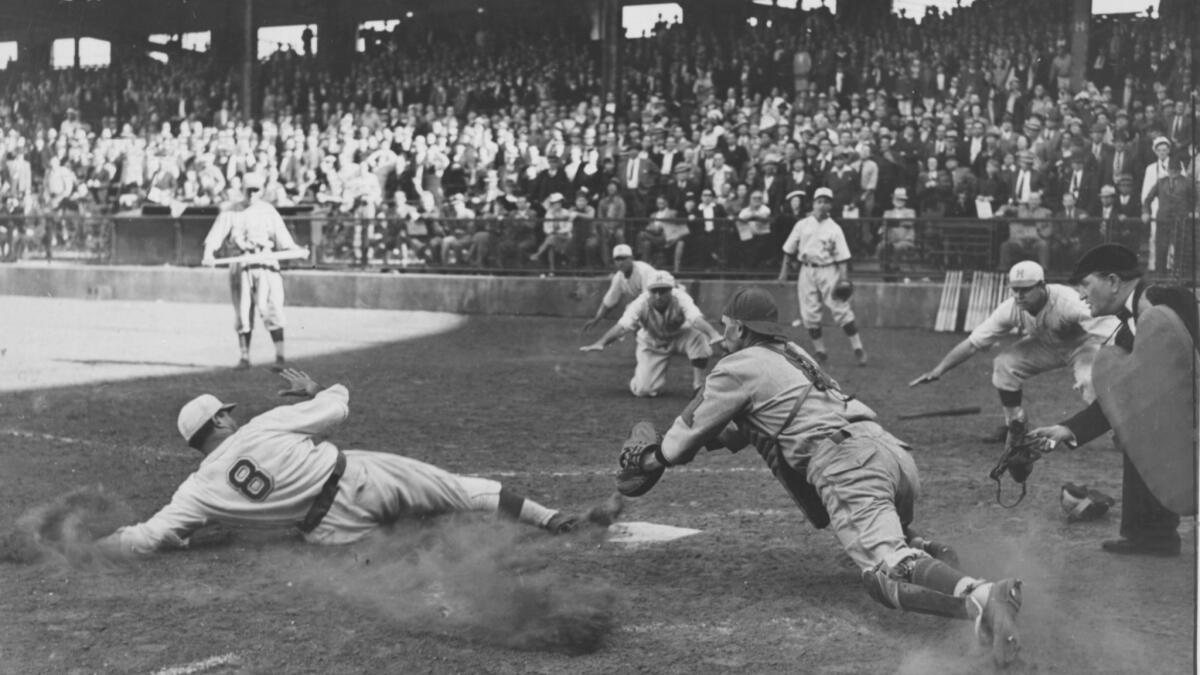

When baseball was king in America, the Hollywood Stars were royalty in Los Angeles.

They were minor league in name only. Bing Crosby and Gene Autry owned pieces of the team. So did Cecil B. DeMille and Gary Cooper, and George Burns and Gracie Allen.

The team promoted itself as “the Hollywood Stars baseball team, owned by the Hollywood stars.”

Jayne Mansfield was “Miss Hollywood Stars.” Elizabeth Taylor was a bat girl. The team president for a time was Bob Cobb, the restaurateur who lent his name to the Cobb salad.

In 1958, the Dodgers migrated from Brooklyn, displacing the Stars and their crosstown rivals, the Los Angeles Angels.

Major league baseball had arrived in Los Angeles. Minor league baseball in the city was no more.

Minor league teams sell fun and affordability rather than the promise of victory, a pitch traditionally regarded as best suited for small towns, where the options for family entertainment tend to be limited.

In recent years, as major league ticket prices have skyrocketed, minor league teams have staked out a successful niche on the fringes of urban areas, in the shadows of such baseball behemoths as the Boston Red Sox, Chicago Cubs and New York Yankees.

The Dodgers liked the concept. They found an ideal spot for minor league baseball to return to Los Angeles, for the first time in six decades. They quietly lined up financial and political support.

A dying mall could be re-imagined as an intimate ballpark, where fans could come face to face with up-and-coming players, not just look up at a famous face on a distant video board.

In the end, politics killed the plan. Not the politics of the city, but the politics of baseball.

Star power

The Hollywood Stars played at Gilmore Field, on Beverly Boulevard just east of Fairfax Avenue. After the Stars left, the field was demolished, and on that land rose CBS Television City. James Corden tapes his “Late Late Show” there, in the afternoon.

The site is adjacent to Farmers Market, which dates to 1934, and the surrounding Grove, which dates to 2002. The Grove is an oft-cited example of the post-modern mall.

In an era where department stores are dead, and you can shop from home with a click, the post-modern mall lures consumers with specialty retailers, entertainment, and sanitized adventure. At the Grove, you can ride a trolley car, hear live music, and gaze at fountains of dancing water.

In Woodland Hills, at the Village at Westfield Topanga, you can visit a yoga studio, dance studio, day spa, gym, health clinic, and Briella, a “metaphysical retail environment” that features a “crystal healing corner.” The Village offers indoor and outdoor dining, high-end boutiques, bocce ball courts, and live music.

As Westfield prepared to open the Village in 2015, the company that designed and developed retail destinations all over the world pondered what to do with its Promenade mall, across Erwin Street from the Village.

At the start of that year, Macy’s closed both of its stores at the Promenade, which already had been hemorrhaging tenants. The movie theaters still did brisk business, but the interior was one vacant storefront after another.

“We had an obsolete mall,” said Peter Lowy, then Westfield’s chief executive officer.

Lowy and Peter Guber, the former chief of Sony Pictures, were old friends and onetime business partners. Lowy’s company had put up a high-end mall next to London’s Olympic Stadium. Guber, producer of such films as “Rain Man” and “The Color Purple,” had owned eight minor league baseball teams under his Mandalay Sports Entertainment banner.

In 2012, Guber joined the Dodgers’ new ownership group. In 2014, he led an investment partnership that bought the minor league team in Oklahoma City. The Dodgers would run that team, which competes at the triple-A level, the highest in the minor leagues.

The Dodgers also employ players at Class A, three levels below the major leagues, at Rancho Cucamonga of the California League. They do not own the team.

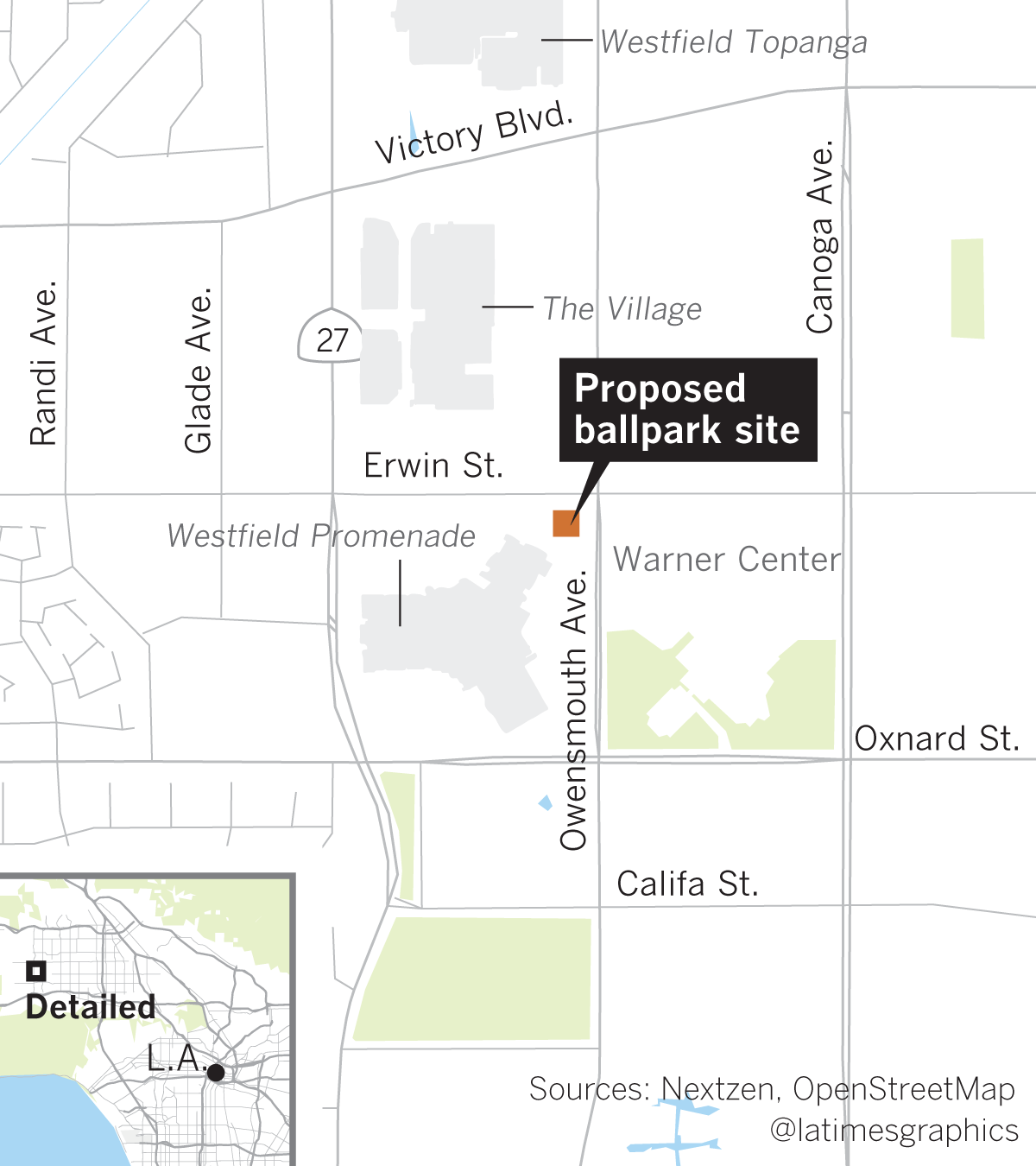

Lowy had the land. Guber could get a team. The two hatched an idea: Why not buy a California League team, put it in Woodland Hills, and let the Dodgers run it?

Westfield would relocate the movie theaters, then demolish the Promenade and build a 7,000-seat stadium, perhaps with a pedestrian bridge linking the ballpark to the Village.

That post-modern mall would boast an unusual amenity: a venue that would welcome locals for 70 minor league baseball games each year, concerts, youth sports competitions and community events. Fans could dine out, work out, shop, and catch a game or show, all without moving their car.

“I always thought it would be a fantastic idea to incorporate a small stadium in with the retail, in the suburbs,” Lowy said. “That’s one of the largest retailing areas in the country. It’s got a dense population.

“Instead of making people go to where the game is, why don’t we bring the game to where they live?”

The business plan did not depend on fans giving up the chance to see marquee players such as Clayton Kershaw or Cody Bellinger at Dodger Stadium, just because they could see anonymous minor leaguers wearing a Dodgers cap and playing closer to home. That would have been folly.

But the San Fernando Valley is the Dodgers’ turf. And, by itself, the valley’s population is 1.8 million, bigger than any city on the West Coast outside Los Angeles.

“Where else would it be better to have a minor league team for the Dodgers?” Lowy said. “I think it would have been sold out for every game.”

Making a pitch

Lowy put the Westfield architects to work on stadium design. Guber lined up financial partners and secured the support of Mark Walter, the Dodgers’ chairman, and Stan Kasten, the team president.

“This wasn’t going to be some big money-maker,” Guber said. “It was marginal in that respect. But it would have been great for the Dodgers. We thought it would have been fun.

“The team wouldn’t have been something somebody would follow in the Los Angeles Times, but we felt it could be a really good incubator for executive talent, and for trying out new fan initiatives.”

Their timing was right.

For more than a decade, the California League had wrestled with the future of its teams in Bakersfield and Adelanto. Major league teams campaigned for new ballparks in both cities, hesitant to dispatch their minor leaguers to play in outdated facilities.

For 75 years, the Bakersfield franchise played in a converted county fairground at which the sun set into the eyes of the batter. In Adelanto, home of the High Desert Mavericks, the relationship between the city and the team grew so chilly that the city tried to evict the team from the stadium.

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

When Kasten shared the Dodgers’ plan with Pat O’Conner, the president of Minor League Baseball, O’Conner envisioned a solution to half of his long-running dilemma. The Dodgers could buy either the Bakersfield or Adelanto team, and O’Conner could figure out what to do with the other team.

“Any time you have an opportunity for a major league club to stabilize a franchise in their general area, there’s a whole lot of synergy, a whole lot of positives to that,” O’Conner said.

Eric Garcetti thought so too. The mayor of Los Angeles played his boyhood baseball at Encino Little League, eight miles from where the Dodgers would have put that minor league team.

“When they talked about Woodland Hills, I thought it was a natural,” Garcetti said.

Garcetti loves his Dodgers. He attended the World Series last season, and opening day this season. He noticed the prices.

The Dodgers gave away Bellinger bobbleheads in April, with tickets sold on the team website starting at $37. If you wanted to sit on the field level, tickets started at $75.

On June 28, you can get a Bellinger bobblehead at a California League game in Rancho Cucamonga. Tickets start at $10, and every seat is on the field level.

“It’s so expensive to take a family to a professional sporting game,” Garcetti said.

“If you’re a Dodgers fan, you have to subscribe now, just to watch them on TV. Or you don’t, if you subscribe to the wrong [cable or satellite service]. Baseball was the great accessible sport for everybody. It was really America’s sport. Now it is further and further out of reach. I think the minor leagues are prospering because of that.”

There was another critical factor in Garcetti’s support of the project.

“We wouldn’t have needed a dime from the city,” Lowy said.

Westfield owned the land. The parking already was there. The city would not have to entertain the potentially spurious promises that construction of a ballpark would trigger economic development in the surrounding area, because Westfield already had developed The Village.

The proposed ballpark site was surrounded by commercial property, so the effects on nearby homeowners would have been minimized. And, if the site could handle holiday shopping traffic, surely it could manage the impact of a minor league ballpark.

“It’s less than having a Costco there, for sure,” Garcetti said. “There’s always somebody who is going to be against it. But nobody wants to jump on the 101 for two hours to get to Dodger Stadium if they can see some games right in their backyard.”

Guber and the Dodgers liked the Woodland Hills project. Lowy and Westfield liked it. The mayor of Los Angeles liked it. The president of the minor leagues liked it. Rob Manfred, the commissioner of Major League Baseball, liked it.

“There was nobody that did not like it,” Guber said, “except for Arte Moreno.”

Moreno is the owner of the Angels. Under baseball rules, the Dodgers and Angels share the same territory: Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura counties. They can play anywhere within that territory.

So, if the Angels wanted to move from Anaheim to Woodland Hills, the Dodgers couldn’t block them. But, if a minor league team wanted to play anywhere within that territory, the Dodgers and Angels would have to approve.

Guber did not consider that a major hurdle, or even a minor one. The Dodgers would be putting their California League team 55 miles from Angel Stadium — 15 miles farther than Rancho Cucamonga is now. How, he wondered, could that hurt the Angels?

Guber and the Dodgers offered various incentives, including the chance for Moreno to make a few more bucks by granting the Angels a disproportionate share of home games in the annual preseason Freeway Series against the Dodgers.

The Dodgers even solicited Manfred’s assistance in facilitating a resolution. Moreno said no.

“He wasn’t mean or anything,” Guber said. “He was just indifferent to any of our propositions.

“He has a right to do anything he wants. We have no quarrel with that. … But it certainly didn’t leave a good taste in our mouths, in terms of our relationship in the marketplace.”

The Angels had no idea what their future might hold. They would have granted permission for the Woodland Hills team, vice president Tim Mead said, if the Dodgers would have promised to grant permission should the Angels ever wish to move a minor league team within the shared territory.

Even into Los Angeles? Maybe someday, the Angels said. No, the Dodgers said.

Moreno politely declined to discuss the issue.

Manfred, asked about the matter outside an event this spring, pursed his lips, declined comment, then stepped into a waiting vehicle.

Moving on

The timing no longer is right.

The minor league teams the Dodgers targeted for purchase are no longer available. Minor League Baseball ran out of patience with Bakersfield and Adelanto, and the teams moved to North Carolina in 2017.

The San Fernando Valley still lacks a major sports venue and community gathering place. In February, Major League Baseball and its players’ union pledged $1 million to Cal State Northridge so the school could install lights at its cozy baseball field, in the hope that night games and youth programming there could make the field something of a community center.

Lowy no longer runs Westfield; the company was sold to a competitor last year. Plans for the Promenade site promise homes, offices, hotels, shops and even a 15,000-seat sports arena by 2035.

The Woodland Hills ballpark would have been up and running by now. Instead, even the Wikipedia listing for the Promenade describes it as a “dead shopping mall.”

The doors are locked, affixed with signs reading “Interior Mall is Closed.” The movie theaters still do well, but the rest of the interior has been walled off.

On a recent Saturday, one of those walls — separating the theater from what used to be a food court — was plastered with an ad for the movie “Pet Sematary.”

The slogan for the movie hit a little too close to home for the mall: “SOMETIMES DEAD IS BETTER.”

Follow Bill Shaikin on Twitter @BillShaikin

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.