How Brent Honeywell learned to throw a screwball, a pitch notable in Dodgers history

- Share via

Jarren Duran looked back at the mitt of Dodgers catcher Will Smith, where a funky 82-mph pitch from right-hander Brent Honeywell had just landed after breaking down and away from the left-handed-hitting slugger.

Then the Boston Red Sox star shot a glance at home-plate umpire Laz Diaz, who rang up Duran on a called third strike that was outside of the zone to end the top of the ninth inning of an eventual 7-6, 11-inning Dodgers victory on Saturday.

“When you’re fooling the umpires,” Dodgers reliever Alex Vesia said, “that’s a pretty good pitch.”

The pitch in question was a screwball, once known as a “reverse curveball,” a pitch that Fernando Valenzuela made famous in 1981, when the Dodgers left-hander went 13-7 with a 2.48 ERA and eight shutouts to win the National League Cy Young and Rookie of the Year awards.

On the day he reached 10 years of MLB service time, Kiké Hernández helps lead the Dodgers to a 7-6 comeback victory over the Boston Red Sox in 11 innings.

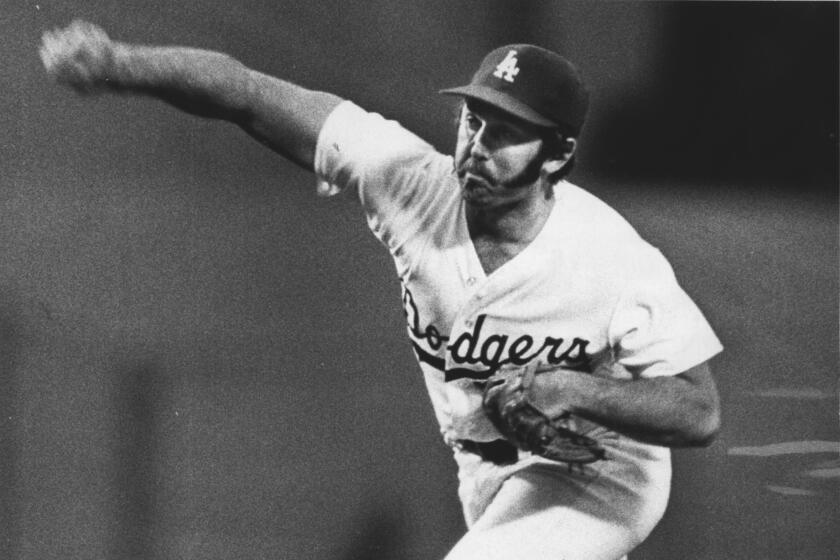

It was also a pitch that Mike Marshall used heavily in 1974, when the Dodgers right-hander went 15-12 with a 2.42 ERA and 21 saves and threw 208⅓ innings in a major league-record 106 relief appearances to win the NL Cy Young Award.

The screwball is so rare that Honeywell is believed to be the only current major leaguer throwing the pitch, which left-hander Hector Santiago threw for five teams, including the Angels, from 2011 to 2019.

And in another statistical oddity, a through line can be drawn almost directly from Marshall five decades ago to Honeywell, who was designated for assignment by the Pittsburgh Pirates on July 12, claimed by the Dodgers and has allowed only four hits in eight scoreless innings of his first four appearances with his new club.

Marshall, who died at the age of 78 in 2021, and Honeywell’s father, Brent Sr., were cousins. Marshall, who played 14 years (1967-81) in the big leagues, was the head coach at Saint Leo University, a Division II school in the Tampa Bay area, from 1984 to 1988. Brent Honeywell Sr. pitched for Saint Leo from 1985 to 1988.

“Mike Marshall taught my dad the pitch, and then my dad taught me the pitch when I was in high school,” Honeywell said. “I’ve been throwing it my whole career.”

The movement of the screwball, which breaks toward the arm side of a pitcher, is caused by an unorthodox motion that requires a pitcher to pronate his hand and forearm, the snapping of his wrist causing his palm to face away from his glove side.

Many coaches believe the pitch puts too much stress on the arm, a notion Honeywell disputes even though he underwent four elbow surgeries, including a Tommy John procedure, that sidelined him for 3½ seasons from 2017 to 2021.

“I think any pitches are taxing, so that’s a full-blown myth,” Honeywell, 29, said. “It’s easy to say because no one else throws it, but it’s just like driving a car that’s faster than others. As soon as something goes wrong with it, it’s like, ‘Oh, it’s too fast,’ and no one knows how to fix it.”

Mike Marshall, who won the Cy Young Award for the Dodgers in 1974 when he pitched in a major league-record 106 games, died on Tuesday.

There is nothing fast about Honeywell’s screwball, which averages 80.8 mph and, according to Baseball Savant, features an average drop of 45.1 inches and an average left-to-right break of 7.9 inches.

It is one of three secondary pitches, including an 85.7-mph slider and an 82.1-mph sweeper, that Honeywell uses to offset a four-seam fastball that averages 94.8 mph.

“The goal is to catch hitters off-guard,” said Honeywell, who was a second-round pick of the Tampa Bay Rays in 2014 and didn’t make his big-league debut until 2021. “But it’s just one pitch in a pretty wide repertoire.”

Honeywell came up through the Rays’ farm system as a starter, and he showed in his first game with the Dodgers, when he threw 36 pitches over three scoreless innings in a 4-3 loss at Detroit on July 14, he can provide multiple innings.

“That night he pitched in Detroit was the first time I’ve ever seen him,” said Rick Honeycutt, 70, the former Dodgers pitching coach who transitioned to a special assistant role in 2020.

“He’s got my old number (40), and I didn’t see the last four letters of his name on his jersey when he was pitching. I actually texted Orel [Hershiser, Dodgers broadcaster] and said we’ve got another ‘Honey’ wearing No. 40.’ ”

Honeycutt, who spent five years (1983-87) of his 21-year career with the Dodgers, joined the team on the last homestand and saw Honeywell blank the Red Sox on one hit in the eighth and ninth innings last Saturday and blank the San Francisco Giants on one hit in the sixth and seventh innings of Tuesday night’s 5-2 win.

Honeywell then recorded his first career save in Thursday’s 6-4 win over the Giants, giving up a leadoff single to Heliot Ramos in the ninth inning, getting Matt Chapman to ground into a double play and striking out Patrick Bailey.

“Honeywell has been great,” manager Dave Roberts said. “He’s very confident. I love the strike-throwing aspect. It’s a funky changeup-screwball. I think we’re getting him at the right time — you know, a guy who’s been kicked in the teeth and kind of on the outs and then he has a new start. As a 29-year-old player with not a lot of [major league] service, I think he’s just scratching the surface.”

Honeywell whiffed Bailey with a 97-mph fastball to finish Thursday’s game, but he used an 80-mph screwball to induce an inning-ending double-play grounder from Rob Refsnyder to end his outing against the Red Sox.

“You don’t see that pitch a lot, but when you see the success Fernando had with it, and that was Marshall’s No. 1 go-to pitch — he was a bull out there — you’d think more people would have continued to throw it,” Honeycutt said.

Does Honeycutt, who has spent more than five decades in the game, think the screwball is too taxing on the arm?

The Dodgers head into the All-Star break after blowing another ninth-inning lead Sunday in Detroit, yet they still lead the NL West by seven games.

“I couldn’t give you a good estimation about that because Fernando obviously pitched a long time with it, and Mike Marshall was able to do it,” Honeycutt said. “You could probably learn it, but you would have to have somebody who was somewhat of an expert at it to teach you.”

For Honeywell, that expert was his father, who pitched for three seasons (1988-90) in the Pirates organization but never rose above the Class-A level.

And for the elder Honeywell, that expert was Marshall, who went 97-112 with a 3.14 ERA during his 14-year career and went on to work as an independent pitching coach and consultant, teaching theories of kinesiology, mechanics and training techniques that many in baseball deemed too unorthodox for mainstream use.

“He was pretty good at his job, and I think he was pretty good about everything else around baseball,” Honeywell said. “Whether he was liked or not, he moved the game forward, and that’s all he wanted to do. He didn’t have any skin in the game, other than wanting the game to be better.”

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.