Appreciation: Keith Jackson was college football, authentic, homespun and wonderful

All I can think: Now Dick Enberg has a drinking pal.

Keith Jackson was like a big slab of country ham. And a national treasure. We miss him already.

“The very best place to take a nap is in the back of a cotton wagon,” he told me once, in that lovely Southern cadence sports fans loved from coast to coast.

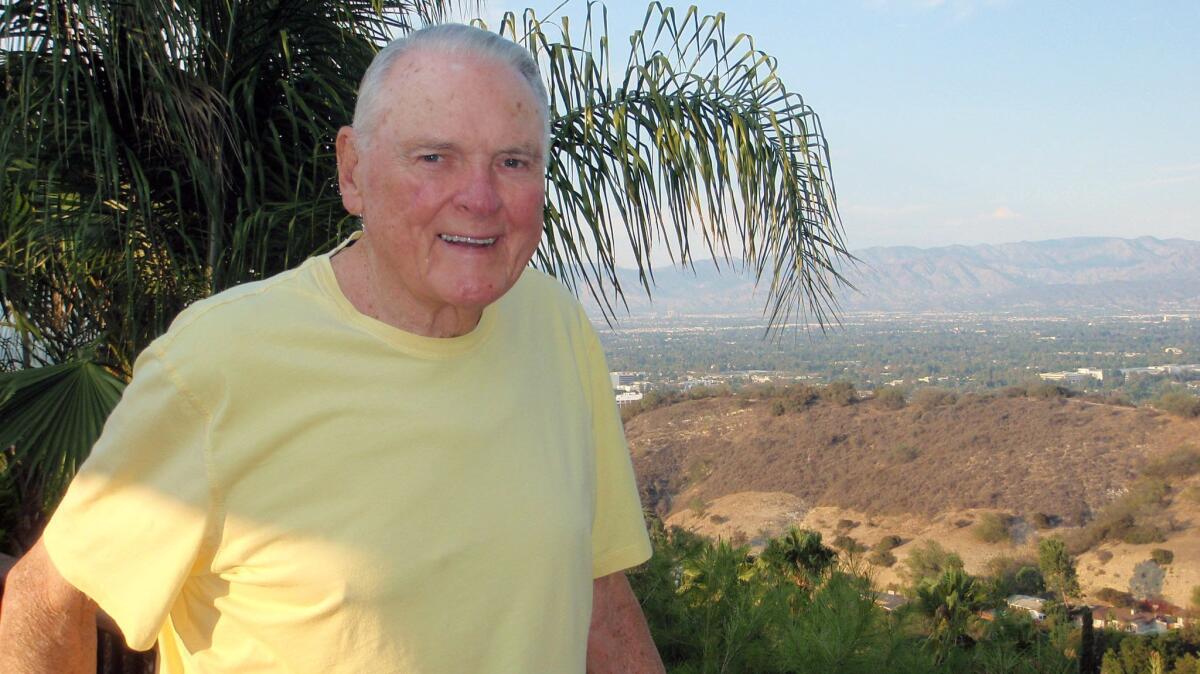

Jackson, whose death at 89 was announced Saturday, lived for 50 years in the same Sherman Oaks home with views that reached clear to the Rose Bowl, a stadium he graced with his remarkable voice, which he used like Rembrandt’s brush.

His calls were melodious, up and down the scale — never losing the clippity-clop of his Southern upbringing.

The great sportscasters — and Jackson was truly great — all have a three-octave range and an understanding of story line and plot points, knowing instinctively when to speak and, more importantly, when not to.

“They talk too damn much,” he said once, in describing today’s yappy young announcers. “You wear the audience out.”

In his long career, Jackson covered everything — rowing, baseball, boat races and Olympic Games. But it was college football that fit him best. Born in Georgia, he reminded you of an old Southern line coach, broadly built and with a bit of barroom bluster, like his growling soulmate Bear Bryant, with whom he used to pal around.

Jackson belongs on any list of the greats of the game, who mostly came out of radio, when voice timbre mattered more and you had to learn how to stretch a story between pitches and first downs.

It’s probably something you’re born to do.

Like traveling troubadours, they showed up each weekend in your den. You’d kick back, you’d smile and nosh, as they reported in from Ann Arbor, Green Bay, Tuscaloosa and other autumnal garden spots.

In the ’60s and ’70s, Jackson, Ray Scott, Curt Gowdy and Enberg (who passed away only three weeks before) sold us a muddy, bloody, hugely territorial game we soon grew to adore.

They had stories and they had gravitas, something the latest generation of sportscasters sorely lacks.

But persona comes with time, distance and perspective. You get a lot of that when you join the Marines at 16, as Jackson did. Jack Whitaker landed at Omaha Beach and marched to Berlin. Jack Buck won a Purple Heart. If that doesn’t give you perspective and a wry understanding of goal line stands, nothing will.

Jackson came from the generation of play-by-play talents, now mostly gone, who didn’t just develop a style, they assembled a dictionary. Every fan at that time remembers Jackson’s signature phrases, “Whoa Nellie,” “fum-BULLLLL,” and “big uglies” — referring to linemen — and how he anointed the Rose Bowl “The Granddaddy of ’em all.”

In his off-hours, he liked a nice glass of red wine with the best sidekick of all, his wife, Turi Ann, and an occasional round of golf in his adopted Southern California.

“He was an excellent golfer who was kind and thoughtful,” Vin Scully recalled Saturday. “I played with him once and he was not only a great player but he kindly spent a lot of time helping me look for my ball.

“It might have been the result of his time in the Marines, but despite his old country boy technique, he had a quiet dignity about him.”

Jackson told me once that he never got nervous before a telecast, yet kept a slip of paper in his pocket with a few prompts, because he’d seen other broadcasters freeze during openings.

He never needed it.

Probably because he was a natural story teller. He had a million of them, offbeat and obscure, gleaned from six decades chasing sporting events across the globe, but most of them involving football.

He could tell you how Amos Alonzo Stagg “studied the ministry but couldn’t deliver a sermon ... he had heart palpitations. So he became a football coach.”

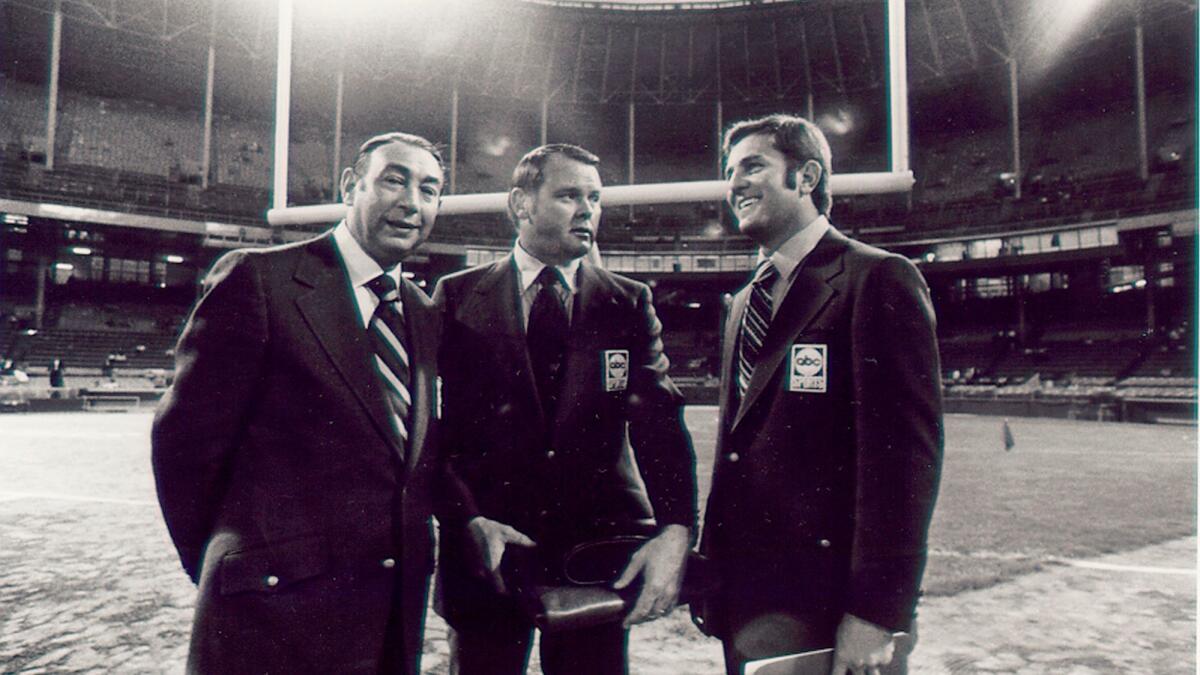

My favorite was about the inaugural season of “Monday Night Football,” in 1970, when Jackson was the play-by-play voice alongside the brilliant-yet-boastful Howard Cosell and “Dandy” Don Meredith.

To this day, there has never been a broadcast booth quite like it.

“It was 28 degrees in Philly and Cosell had been drinking for three hours,” Jackson recalled a few years ago.

Before it was over, Cosell had flipped his cigar under the desk and lighted Jackson pants on fire in the middle of the telecast.

Jackson wasn’t the only victim. “Howard did throw up all over Meredith’s cowboy boots,” Jackson recalled.

And you thought you had workplace issues?

Almost 50 years later, Cosell remains the bigger name, but not nearly as beloved. The two sportscasters were reflections of where they grew up: in Jackson’s case, Georgia and Washington; in Cosell’s, New York. They were both colorful, in their own ways. And carbon copies of no one.

Over the years, Jackson’s partners in the booth included Jackie Robinson, Frank Broyles, Bud Wilkinson, Bill Russell, Dick Vitale, Dan Fouts and Bob Griese.

Broyles, Fouts and Griese are the ones I’ll remember best, but it is Jackson most of all — his round, shining smile blushed by a November day, and the joys of a profession he adored.

Twitter: @erskinetimes

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.