Jim Brown, Buddy Miley represent two vastly different sides of football

Life is all about collisions. Having them, avoiding them, learning from them.

A recent day brought one between Jim Brown and Buddy Miley. The former is famous and the latter is not. That added to the fascination.

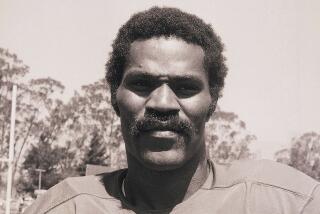

Brown is one the better football players ever. He led the NFL in rushing eight times as a member of the Cleveland Browns from 1957 to 1965. He also appeared in several dozen movies, some of them quite good. He is 77.

Miley was a football player at a suburban Philadelphia high school in 1973. He was a good quarterback, maybe going to be great. Then, in a game, he was tackled hard and never had the use of his limbs again. He was a quadriplegic at 17. When a fly came to rest on his face in the middle of the night, he had to call somebody to shoo it away.

Buddy Miley died at 41, on March 19, 1997, in Room 146 of a Quality Inn in Livonia, Mich. He was assisted in his suicide by Dr. Jack Kevorkian, known as “Dr. Death.”

Jim Brown didn’t know Buddy Miley.

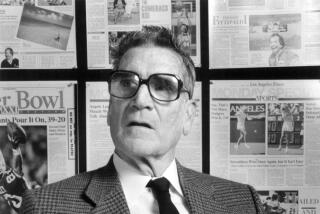

Our luncheon meeting was about Brown’s role in a retirees lawsuit against the NFL that has resulted in something called the Common Good Fund. A Minnesota court has, since 2009, been ruling on an issue initiated by former Ram Fred Dryer over the league’s use in NFL Films of former players’ images without compensating them.

If all the i’s are dotted and t’s crossed in time for a Sept. 19 hearing, the NFL will contribute $42 million to this Common Good Fund. A board of former players, approved by the court and led by Brown, will be mandated to use the money to help NFL retirees in medical or financial need.

That’s a synopsis. It is much more complicated. Many NFL retirees are against it. They see it as too little too late. They don’t trust that the money will get to the most needy, which Brown says is the entire point. Nor do they trust that the NFL’s willingness to write the $42-million check is anything more than a public relations move to build a case against the deluge of concussion lawsuits that could, conceivably, put the most successful pro sports league in the United States out of business.

Brown likes the independence of the board of the Common Good Fund. “We can identify the needs of our players and brothers ourselves,” he said. He also spoke to his vision of investment and growth potential of the fund from NFL marketing and licensing partnerships.

“The $42 million is not the end, just the beginning,” he said.

Buddy Miley’s spot at the luncheon table was conceptual. A recently released book about him, “Like Any Normal Day,” written by Mark Kram, was fresh in my mind. It collided harshly with Brown and his sport.

Brown even used that word. “If you ask me if I’d make the same decisions [about playing football], there’s no doubt about it,” he said. “Collisions will take place. That’s part of it.”

I pushed the line of questioning. He noticed and phrased his answers carefully, yet with conviction. Miley remained in my mind but never was placed on the table. The topics were of the rugged physical nature of football, plus concussions and the often life-crippling injuries for which he soon will be in position to direct compensation.

One fascination is that Brown wouldn’t need to be doing what he is doing if his game hadn’t beaten up so badly so many of his fellow players.

“Football gave a lot of young people opportunities,” he said.

He also said, “You’re gonna be tested, tested in life. I tested myself and it made me a better man.”

Brown said he has six grandsons; all played some level of football and he never worried. “My most serious injury was a twisted ankle,” he said.

He had both hips replaced seven years ago but said “my knees are good.”

Brown is a symbol of excellence and achievement in a game that he played with joy. Miley is a symbol of anguish and disaster in a game he played with joy. Neither represents the norm.

In November 1992, Dennis Byrd suffered a fractured neck in an NFL game and was paralyzed from the neck down. Sports Illustrated ran a story with a headline that used the word “carnage.” A short time later, a letter came in to SI.

It said, in part: “My son broke his neck 19 years ago playing high school football. Since then, our home has been hell on earth … I am sure the majority of SI readers love football. I ask them to spend one day with my son.”

The author was Buddy Miley’s mother, Rosemarie, who brushed away flies in the middle of the night for 24 years.

Jim Brown is in the Hall of Fame. Miley is six feet under in a casket. No easy conclusions here. Just difficult collisions of thought.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.