1968: Long before Colin Kaepernick, David Meggyesy began NFL national anthem protest

- Share via

David Meggyesy couldn’t bring himself to show deference to the American flag.

While every other member of the team stood at attention and followed the NFL directive on conduct during the national anthem — helmet under left arm, right hand over heart — the St. Louis Cardinals linebacker feigned a bad case of the jitters.

The burly defender, whose shaggy brown hair was a defiant departure from the flattops of his football forefathers, dropped his head, scuffed the dirt with his cleats and spit on the ground. As the familiar strains of the song filled Busch Stadium, Meggyesy waged his quiet protest.

It didn’t go unnoticed.

“A sports columnist wrote a scathing column about me being un-American,” recalled Meggyesy, 76, who at the time had allowed the St. Louis chapter of an anti-Vietnam War organization to set up shop in his house. “So the next home game, in the upper level of Busch Stadium, there was a bed sheet hanging that said, ‘Big Red Thinks Pink.’ In other words, I was a pinko or a commie.”

Meggyesy’s gesture was a blip compared to what happened a few months earlier, when Americans John Carlos and Tommie Smith each raised a gloved fist on the medals stand during the 1968 Summer Olympics. It also was far less obvious than the anthem protest of San Francisco quarterback Colin Kaepernick and others, which became among the most divisive issues in the history of the NFL.

There’s compelling evidence that Meggyesy’s outspoken criticism of the war led to his benching and, ultimately, a premature end to his career. He later wrote the tell-all memoir, “Out of Their League,” chronicling his quest for social justice, and the then-taboo topics of racism, drug abuse and extreme violence in the game.

1968 was among the most turbulent years in U.S. history, and there were seismic shifts in pro football too.

Shortly after Green Bay opened the year by beating Oakland in the Super Bowl, the legendary Vince Lombardi stepped down as the Packers’ coach. Although he stayed on as the team’s general manager for a season, and later would coach the Washington Redskins, it unquestionably was the end of an era.

Meanwhile, the upstart American Football League was on the rise, and the New York Jets made good on “Broadway” Joe Namath’s Super Bowl III guarantee, upsetting the mighty Baltimore Colts in early 1969 and setting the stage for the NFL-AFL merger a year later.

The button-down, horn-rimmed Lombardi and the charismatic, fur-coat-shrouded Namath were as different as “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” and “The Mod Squad,” both of which debuted in 1968. The winds of change were of the gale-force variety.

“You might say it was a cultural revolution,” Namath said. “It was the same way on a football team. You had a group of people that were set in their ways, or people that took offense to other people speaking out about the situation. The music. Jimi Hendrix, Woodstock [in 1969], let’s not forget that. The attire. How we were dressing — the flower children, the love, the long hair.”

In September of the ’68 season, AFL President Milt Woodard sent a letter to the teams insisting the players be clean-shaven. Weeb Ewbank, coach of the Jets, didn’t even bother showing that to his players, many of whom had facial hair. He finally posted it on the bulletin board in December, after the Jets had advanced to the AFL title game. On the cover of the Dec. 9 issue of Sports Illustrated, Namath sported a robust “Fu Manchu” mustache.

“We got a laugh out of that letter. Big laugh,” the quarterback said. “That coach Ewbank was sharp, man. … He showed us something by keeping that letter. That letter was dated September, man, and we didn’t see it. He never said a word to us about cutting hair, shaving, trimming down or whatever. He put that up after we clinched, and we got a big kick out of it.”

Other issues of the times, such as race relations, were more serious. There were far fewer African American players in the league than now, when roughly 68% of the players are black. What’s more, certain key positions were almost exclusively manned by white players.

“The middle of the field was all white — quarterback, offensive center, middle linebacker and free safety,” said Kansas City Chiefs Hall of Famer Willie Lanier, the first full-time starting middle linebacker who was black. “Those were the ones who called out the changes and signals to the different units.”

The Chiefs made sure racial tension never became an issue within the walls of the team, Lanier said, and Kansas City won Super Bowl IV in early 1970.

“In Kansas City, it was almost like we had an unspoken understanding that you left your philosophical views of any- and everything that could be a question at the door,” Lanier said. “You did not bring it into the discussion because there was no place for it if you were going to try to achieve an outcome that was larger than all of that.

“It was fascinating. You could be as extreme to the right — Republican, Democrat, moderate, independent — as you wanted to be, but that could have nothing to do with the way you perform. That’s the only way during that time that our team was able to do what it did.”

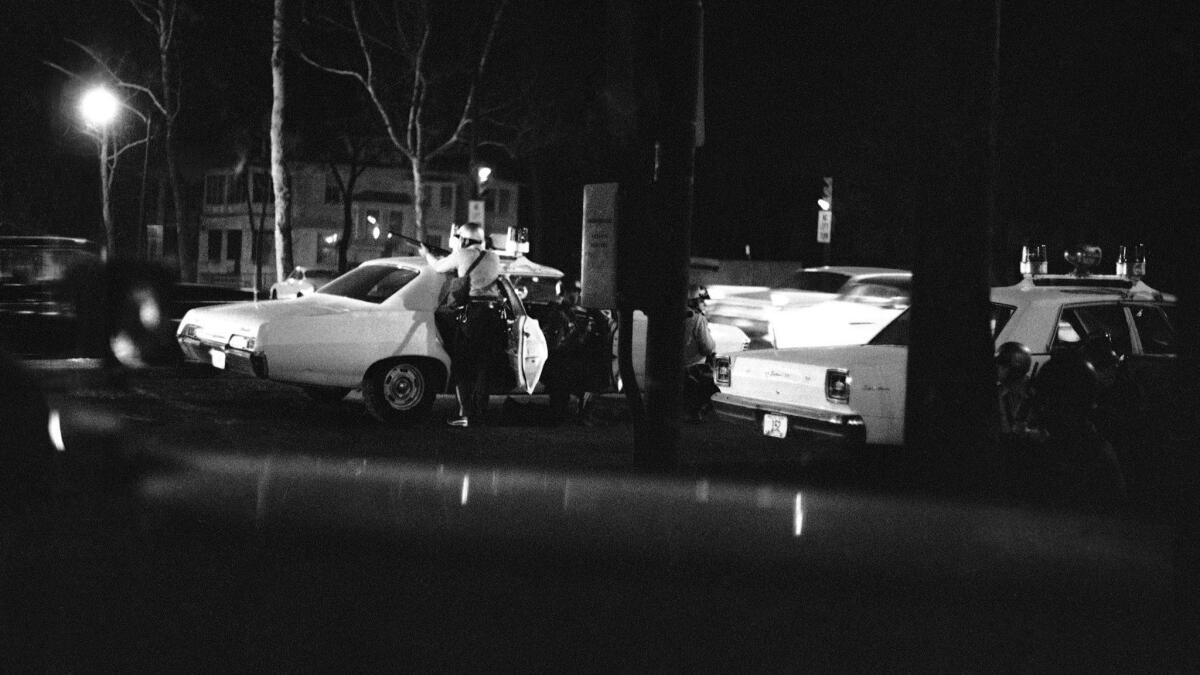

Off the field and outside the locker room could be a different story. Lanier recalled what started as a peaceful demonstration in downtown Kansas City, Mo., after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination devolved into a riot. Six black members of the community died in the clash, which involved 700 police officers and 1,700 National Guard troops.

“You had certain issues as far as housing was concerned,” Lanier said. “They couldn’t rent to me because if they did, they might lose some of their white tenants, and that certainly I should understand. I don’t understand it. It’s not acceptable. But that’s what it was.”

Seven of the 22 starters on the 1968 Jets were African American, and Namath said he and others worked to knock down the invisible walls separating teammates.

“I remember the day that I walked into lunch and there were a few guys sitting at a table that were black,” he said. “The white guys never sat with the black guys. I was tired of that. I went and sat down with them; they were my buddies. By the time we got out to [training camp at] Hofstra … there was a change. … But it’s still out there. It’s still out there today.”

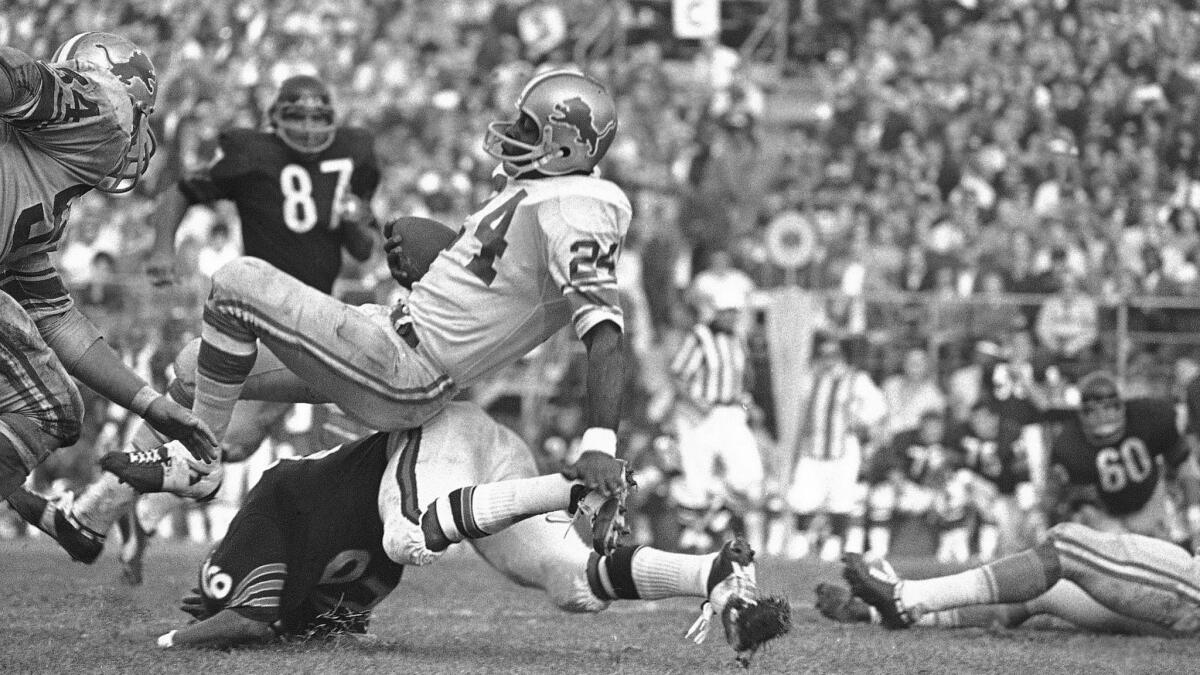

At another training camp, a different sort of drama was playing out. At the urging of two pals on the team, Lem Barney and Mel Farr, the Detroit Lions were hounded into giving legendary Motown singer Marvin Gaye a look.

“We tried him out at tight end, wide receiver, even some fullback,” recalled Barney, a Hall of Fame defensive back. “We thought he was doing good. … They said, ‘We like your attitude, but since you haven’t played any ball, we don’t want to risk putting you out there.’ He was appreciative of that.”

“I don’t think he had played high school football. But by hanging out with Mel Farr and I, seeing us work out and everything, he really felt good.”

A couple years later, Gaye returned the favor, asking Barney and Farr to sing backup on his 1971 mega-hit “What’s Going On.” The classic was a soulful social commentary, inspired in part by Gaye’s brother, Frankie, returning from Vietnam.

Reflective of an era of tumult and transition, it was a different kind of anthem.

Picket lines and picket signs/Don’t punish me with brutality/C’mon talk to me/So you can see/What’s going on

Follow Sam Farmer on Twitter @LATimesfarmer

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.