- Share via

“I’ve got a little … flake in my eye.”

The scruffy bear of a man pulls his sunglasses tight so his football team can’t see his tears.

Andy Hopper, an assistant football coach at Paradise High, has a story to tell. On this August morning in a cluttered school gym, he is telling it to a group of 37 boys wearing baggy shorts and weary smiles.

They are the Paradise Bobcats, teenagers who have stubbornly returned to the mountain to sift through the ashes in search of a football season.

Nine months after the most destructive wildfire in California history turned their town into scorched metal and dust, they are embarking on training camp for an autumn that is as much about healing as winning. They are charged with the rebirth not only of football, but community. Their childhood sport has become a sacred mission and one of the biggest challenges of their young lives.

One month from their first game and three days before their first padded practice, they have gathered to listen to the heartbeat of Coach Hopper.

“November 8 was hard!” he says, and the gym goes silent. “You lose everything; you think it’s the end of the world!”

Sprawled across the hardwood floor, fidgeting just moments earlier, the boys are motionless. They stare at the coach as a trickle leaks from behind those glasses.

“November 13, I got the first opportunity to sneak in,” he says. “I went to look for my grandma’s ashes. I didn’t find them. I keep sifting through that, and you start feeling sorry for yourself and you start thinking nothing is going to be right again.”

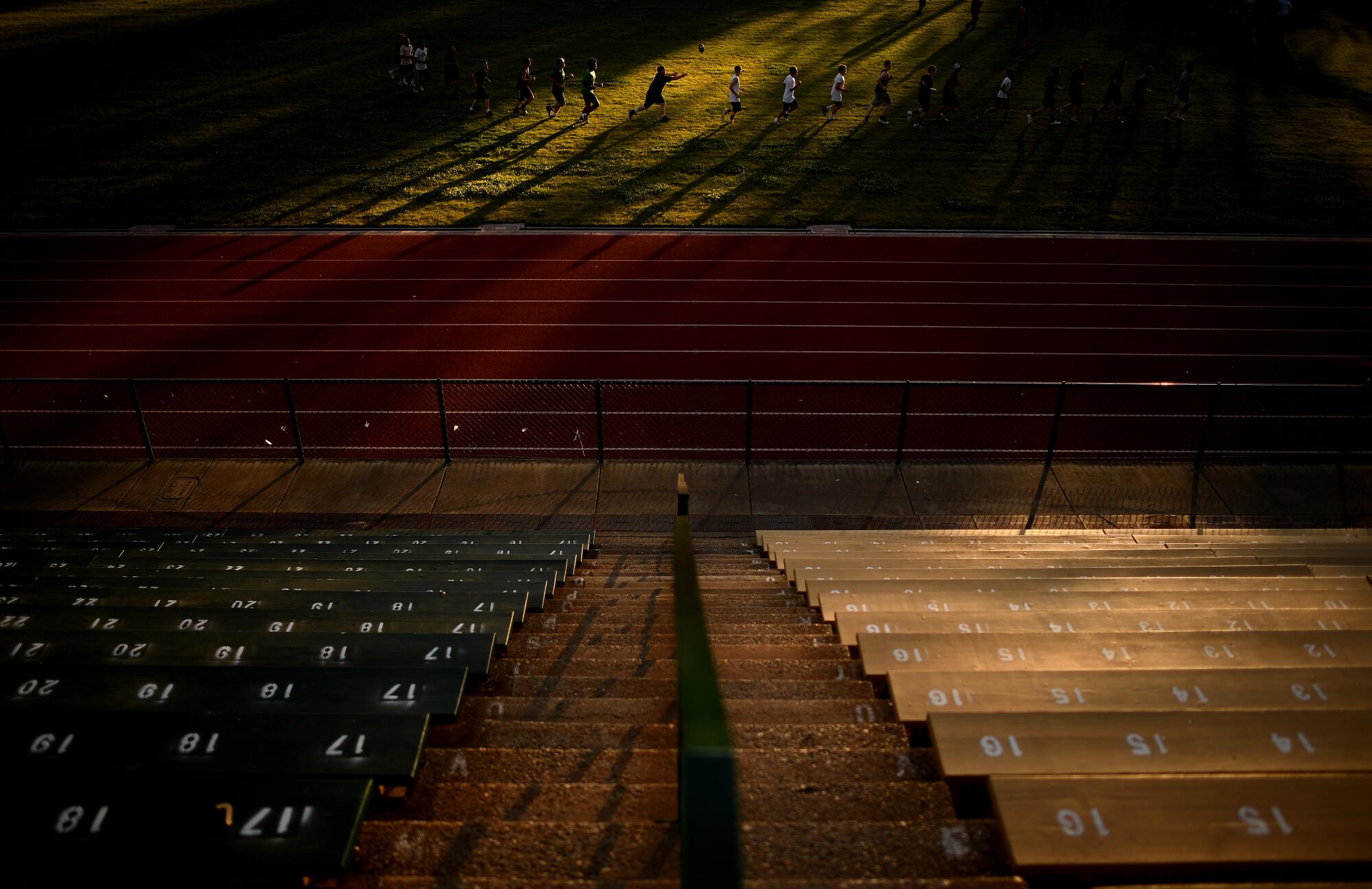

After losing everything in the deadly Camp Fire last year, the Paradise High football team leans on camaraderie and community to rebuild their lives. (Robert Gourley / Los Angeles Times)

As the coach speaks, he is being watched closely by the defensive back who was cornered by the fire before driving himself through hell to safety. And the running back whose mother told him they were going to die in the flames. And the other running back who ran from the blaze carrying only his equipment bag.

“Everything you find … you pick it up, it just crumbles, right?” Hopper says, recalling how he sifted through his destroyed home. “All that stuff that you’re trying to find, it just crumbled. And you start thinking, ‘Woe is me, it’s never going to be right, it’s never going to be the same,’ and I gave up. I couldn’t find a darn thing.”

Standing behind him are coaches who lost everything and didn’t have insurance; coaches who have recently lived in a half-dozen different houses; a coach who lost not only his home but his business; and the fatherly head coach who was going to retire after the season but couldn’t leave his team like this.

“I got pissed off, I threw the freaking netting up, I saw something fly through the air,” Hopper says of the culmination of his search. “And I looked over. And it was this.”

He pulls a small black object out of his pocket and the boys gasp. It is a Paradise football championship ring from 2011. It is badly burned and barely recognizable, but its message is clear.

The ring survived. The victory survives. Paradise football will survive. It must.

“We don’t feel sorry for ourselves. There ain’t one damn victim in here!” Hopper roars. “I feel like God chose us. I’m not saying God created that fire; I’m saying God chose us to say, ‘You know what, I’m going to make these guys the smartest dudes on earth, that they can go through something so horrible and come out the other end and represent to the rest of the world what a man can do.’”

He is shouting, and the Paradise Bobcats are shouting back, fully ready to unleash their pain and fear and fight on the football world.

“You guys want do that this year?”

“Yes coach!”

“You guys want to do that this year?”

“Yes coach!”

::

Somewhere in the night, a helmet bangs. Shoulder pads crunch. A shadowy figure carries the ball into the blackness. A whistle blows. A murky huddle forms.

It figures that the Paradise High football team would begin its comeback in the dark, literally, ending recent summer practices at ancient Om Wraith Field without ever turning on the lights.

“It’s dark?”

The guy with the keys to those lights, defensive coordinator and school landscaper Paul Orlando, says this as if he hadn’t noticed.

The players can barely be seen but can somehow see each other, and they run plays crisply through the gloaming without a stumble. The action embodies the enduring consistency of 20 years of Paradise football under coach Rick Prinz, whose system is run by the children in this football-loving community from the time they are old enough to strap on a helmet. Tradition means even more this year, the players relying on each other in the wake of the devastating November 8 Camp fire that vaporized their town and caused 86 fatalities.

“You have to understand, we’ve all run these plays since we were 10 years old. … We could do it with our eyes closed,” says running back Lukas Hartley. “Nobody notices that it’s dark. Even though we’re not in our houses that burned up, we all feel like we’re home.”

The state of this football team was chronicled in an article published June 1 by The Times. The players have told harrowing tales of their escapes. They have described the pain of losing possessions, the uncertainty of temporary housing, and the frustration of having a potential championship season abruptly end.

“Everybody has been so pulled apart for so long. … This is our chance to bring everybody back together.”

— Rick Prinz, Paradise football coach

When they first gathered in the spring to begin the team rebuilding process, half the players were missing, as was a key piece of equipment. They didn’t have a football.

Now, with the Aug. 23 season opener approaching, they are in the final stages of bracing for a difficult fight. Only three players actually reside in Paradise, whose population has dipped from 26,800 to around 2,000. Virtually the entire team commutes, some as long as an hour each way. They lost their league affiliation because of the enrollment dip, and they are playing a makeshift schedule against some schools twice their size.

But a few key players have returned from temporary housing in distant cities. New equipment has been purchased with insurance money and donations. The campus miraculously survived the fire, and stone bleachers that line one side of the home field will be ready when the Bobcats walk through the stands to their traditional pregame song, Johnny Cash’s “God’s Gonna Cut You Down.”

“There’s a lot more here than just football,” says senior running back Jeff Trinchera. “There’s the town. There’s the people in the town. What we’re trying to do, it’s personal.”

There are so many emotions coursing through this team and this season, Prinz is using summer and training camp workouts to bring everything into focus.

The players will purposely practice in the dark, guided only by memory, because they need to find faith.

They will endure a hilly 2½-mile run through the remains of the town, a journey through twisted metal and crumbling bricks that will leave them vomiting and in tears but will build resolve.

They will finish this three-day session by making public commitments of dedication, words that will confirm their focus. The statements, like the one from Hopper, strike as big as the giant bearded man himself, and they will scream and cry and cheer.

Then they will put on the pads in preparation for the season opener against Williams High, the biggest game in the program’s 61-year history. Attendance is expected to be at least double the town’s current population. The last time the Bobcats played, they were 8-2 and headed for a playoff appearance that was wiped out by the fire.

“These kids have waited for this moment, our community has waited for this moment,” Prinz says. “Everybody has been so pulled apart for so long. … This is our chance to bring everybody back together.”

::

Somewhere under a blanket, a player laughs. Another howls. Smartphones glow. Two boys start wrestling.

For two nights, the team that practices in the dark also sleeps together, retiring to the school gym to spend the night locked away from turmoil. They crowd the edges of the basketball court with air mattresses and mats and a tent, huddled amid the whirring of an air conditioner and the occasional visit by a cockroach.

This is more than a slumber party. This is a homecoming -- the first nights most of the boys have spent in Paradise since the fire.

“They need to feel connected to this place again,” says Prinz, a former youth pastor who shepherds his players’ emotions as carefully as he runs their offense. “They need to remember this is still their home.”

By the time the clock strikes 11 p.m., the rustling has quieted, the restlessness has ended and everyone is seemingly snuggled up comfortably, with one exception.

Taylor Brady, a junior receiver, is lying on the hardwood floor with just his cleat bag as a pillow and a sweatshirt as a cover.

He didn’t bring a sleeping bag. He doesn’t own one. Before this camp, few of the players had sleeping bags; they’d been lost in the fire.

Prinz notices Brady and brings him a wrestling mat and a blanket. Brady, who commuted an hour from his relocated home in Linda, Calif., drops down on it and is soon asleep. Several hours later, he awakens with a realization.

“I don’t care about a sleeping bag, I didn’t need it,” Brady says, standing in the middle of a team on a mission. “I just needed to be here.”

::

The morning after their final practice in the dark, the Bobcats are fed in the school cafeteria for a second straight day by parent Greg Kiefer, who was in the kitchen around the clock preparing the meals because, he says, “We’re all in this together.”

The re-energized players then sprint into daylight on their annual preseason run, although this year even this simple exercise is tinged with pain.

In the past, when training camp was held on junior college campuses elsewhere, the course traversed picturesque mountain trails. This time, it will be on a bike path that winds through a city filled with vacant lots, business signs standing above empty patches of cement and burned wreckage.

And they will wonder, can we outrun the ruins?

“Guys, we’re here, and we’re questioning ourselves maybe a little bit. Can we do it? I don’t know. … Am I good enough? Can we get it done?” assistant coach Nino Pinocchio shouts. “Guys, all we got to do here is … commit yourself like that where there is no option, there’s no going back, and we will do great things this year!”

The run is their first act of commitment. They glide along a path through rubble, waiting for each other at the bottom of the final hill, then charge up with such passion that several lean over a nearby fence and vomit.

Finishing first is Dylan Blood, a senior running back and safety who is running for more than his team.

“This means the world to me,” he says. “There’s a lot of weight on our shoulders. With the town burning down, we want to come out and make everyone proud.”

Finishing last is Barrett Diaz, a junior lineman who initially slowed to a fast walk but began running again when his team wouldn’t leave his side. The Bobcats roared when he sprinted across the finish line.

“I wanted to walk, they kept going, ‘Run, run, run,’” he says. “My legs hurt, my ribs hurt, everything hurts, but this is why I came here.”

After his home was destroyed in the fire, Diaz’ family relocated about 30 minutes away to Oroville. But he is attending Paradise High because he couldn’t bear the thought of leaving the team.

“It sucks sometimes. I really want to quit but I just can’t,” he says. “We’re a family.”

A little later, the camp culminates as each player stands in front of the group to recite their personal, team and character goals for the season. Some players vow to get better grades. Others pledge to listen more closely to their coaches. But eventually the commitments are connected to the ashes.

“My team goal is of course to win a state championship, but I want to do it while making history,” quarterback Danny Bettencourt shouts. “No other team has gone through what all of us have. We have a bond that no one else has.”

John Wiggins, the linebackers coach, calls for no excuses.

“Survivors? Screw that!” he barks. “I’m just stubborn. I ain’t gonna be laying down for nobody. Nobody!”

In the middle of the ceremony, there is a cry from among the players – a rare certainty in the minds of these unsettled teenagers.

“Not a victim but a champion!” shouts Hartley, and everyone murmurs as if in prayer.

::

Finally, they hit.

With three weeks remaining before the first game, the Bobcats are allowed to hit. And man, do they hit.

Undersized linemen crash against each other in collisions that echo off the trees and burned stumps that line the field. Tiny running backs whack each with loud pops that bounce off the partially melted scoreboard.

“Every one of these players has just been itching to get back on the field to hit somebody,” says Kasten Ortiz, a senior tackle. “It’s all leading up to this, getting pads and helmets on; people getting generally pissed off, not at each other, just what we’ve been through.”

The hitting is highlighted during the annual Green and Gold game, a scrimmage last week in front of about a hundred parents and friends.

The players are wearing new gold helmets donated by Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers, who grew up in nearby Chico, but nothing else is quite so sparkling.

“This is going to be our rebuild season, all eyes on us. This is our little town, and I want to be here for it.”

— Elijah Gould, Paradise lineman

Several of the advertising banners hanging from a chain-link fence along the field promote businesses closed because they were destroyed or damaged by the fire. Along another fence hangs the school’s 10 sectional championship plaques, but one is badly burned.

Then there is the field, unlined and unmarked because it only recently was brought back to life after going nine months without water.

The players don’t mind. They may not know where they’re going, but somehow they know exactly where they’re at. Over the loudspeaker wafts the sounds of John Mellencamp’s “Small Town.”

“It’s a shame that microphone can’t pick up these goose bumps,” says Hartley, looking at a reporter’s tape recorder as he stands on the sidelines in glorious sweat. “This is what we’ve all been living for.”

Up in the home bleachers, it feels like a reunion. Families plop down a buck for water, 50 cents for a bag of chips, and gather together to swap recovery stories and search for the good in new beginnings.

“This town needs it, the people need it, the players need it,” says Randy Hays, the team public address announcer who has lived in eight different places since the fire. “Right now, this is the best place in Paradise. Seriously, show me a better place in town!”

These days, it is a place of both triumph and anguish. Trudging from the field late one afternoon is Elijah Gould, a giant senior lineman who is noticeably wincing. He is playing with a torn ACL in his left knee. He was injured playing basketball in the offseason. He convinced his mother he could endure the pain to play one more football season.

“This is going to be our rebuild season, all eyes on us,” he says. “This is our little town, and I want to be here for it.”

His leg may be weak, but his left arm is strong enough for him to flex a giant biceps with a three-letter tattoo written in old English.

“CMF.”

It’s an acronym that appears on the shoulders of a couple of longtime assistant coaches and has long been seen in various store windows and marquees around town. Gould drove to Reno, Nev. and found someone to ink it on him before he turned the legal age of 18. He is the first player on this team to have one. He will not be the last

“CMF is a big tradition in this town,” he says. “I’m just carrying on that tradition.”

The three letters mean different words to different people, but all agree on a definition so ingrained in a singular mindset that the players should slap those letters on their helmets.

As they attempt to rise from the ashes, with the clock ticking toward a season they hope will resemble a resurrection, the Paradise Bobcats are truly, wondrously, Crazy Mountain Folk.

::

This is the second in a series of feature columns by Plaschke on the Paradise High football team that will be published over the course of the season. If you wish to donate to the Paradise High athletics, contact Athletic Director Anne Stearns at astearns@pusdk12.org.

The Camp fire destroyed their town. Now the Paradise High football team is trying to save themselves

The hills that stretch above this grassy pasture were once ablaze, an apocalyptic fire consuming their homes, disrupting their families, melting their childhoods.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.