Painstakingly, snippet by snippet, the parents of former NFL and Stanford football player Stanley Tobias Wilson Jr. collect information about the last day of their son’s life.

It’s agonizing work. Wilson had been locked up for more than five months at the Twin Towers Correctional Facility in downtown Los Angeles after he’d entered a home in the Hollywood Hills during a psychotic break. On Feb. 1, 2023, he was transported by Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies to Metropolitan State Hospital in Norwalk for psychiatric treatment.

He arrived at 9:50 that morning, and 37 minutes later he was pronounced dead. He was 40 years old.

Precisely where did he die? Precisely how did he die? And why, his parents ask, were they given conflicting accounts of his death? It’s been a year and they still don’t have answers.

Under the federal Death in Custody Reporting Act and a California law that took effect last January, when a person dies while in custody the agency with jurisdiction over the correctional facility must post information online within 10 days, including the “manner and means of death.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

No such information has been posted about Wilson because neither the Sheriff’s Department nor the Department of State Hospitals has assumed “custodial responsibility.” In other words, both agencies contend he was in the custody of the other when he died.

Exasperated by their search for answers, Wilson’s parents filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the Sheriff’s Department, the Department of State Hospitals and L.A. County in September, seeking $45 million.

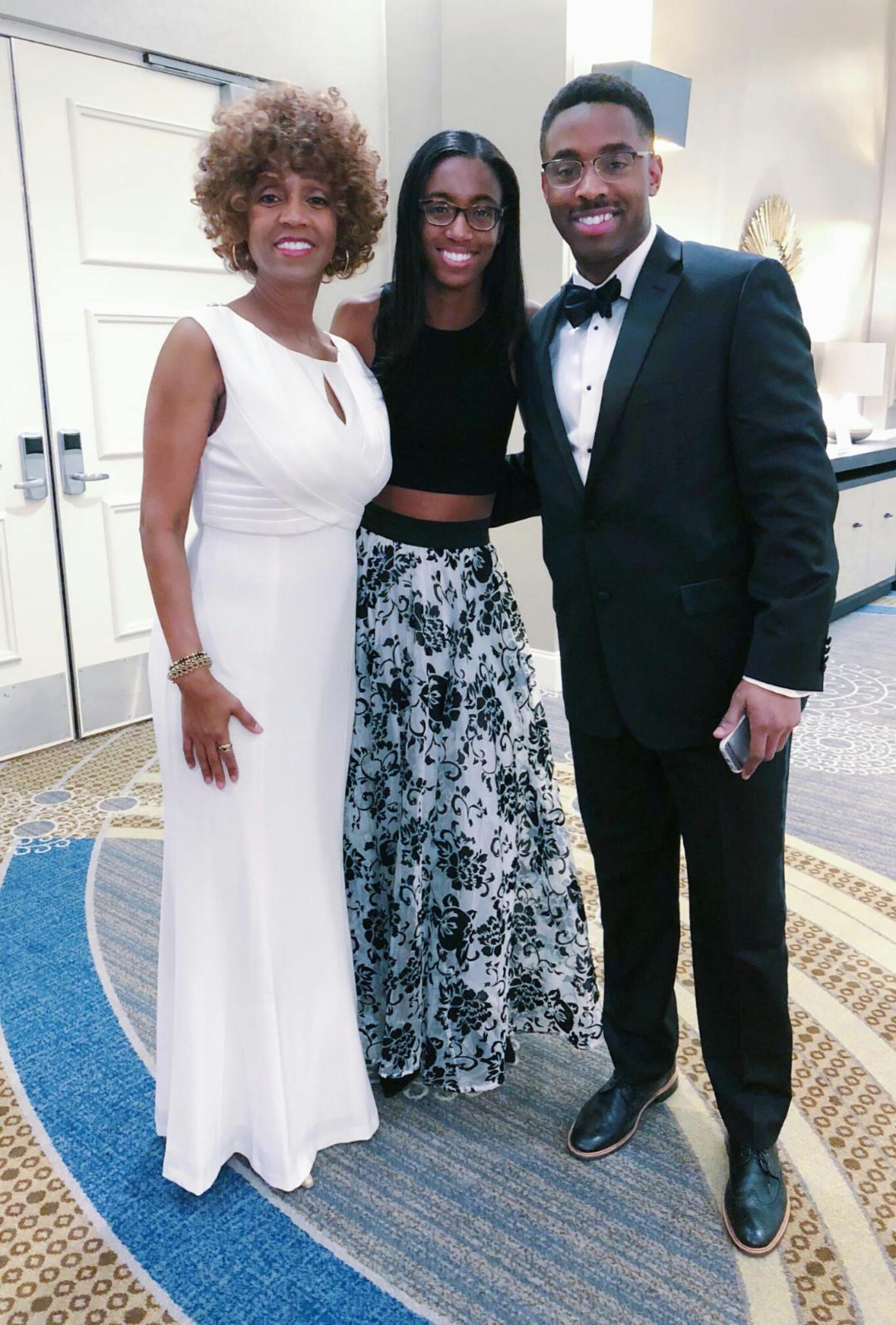

“They didn’t count a person who was a Stanford graduate and an NFL player, so they must not be counting somebody dying in custody who was homeless, somebody estranged from their family, somebody they might think isn’t worthy of being counted,” said Wilson’s mother, Pulane Lucas. “I hope his circumstances can shed light on all the others who are uncounted.”

Other questions about Wilson — about his life and actions — also remain. How did a man with a decorated past and promising future go off the rails? What led to his incarceration? And did blows to the head received while playing football contribute?

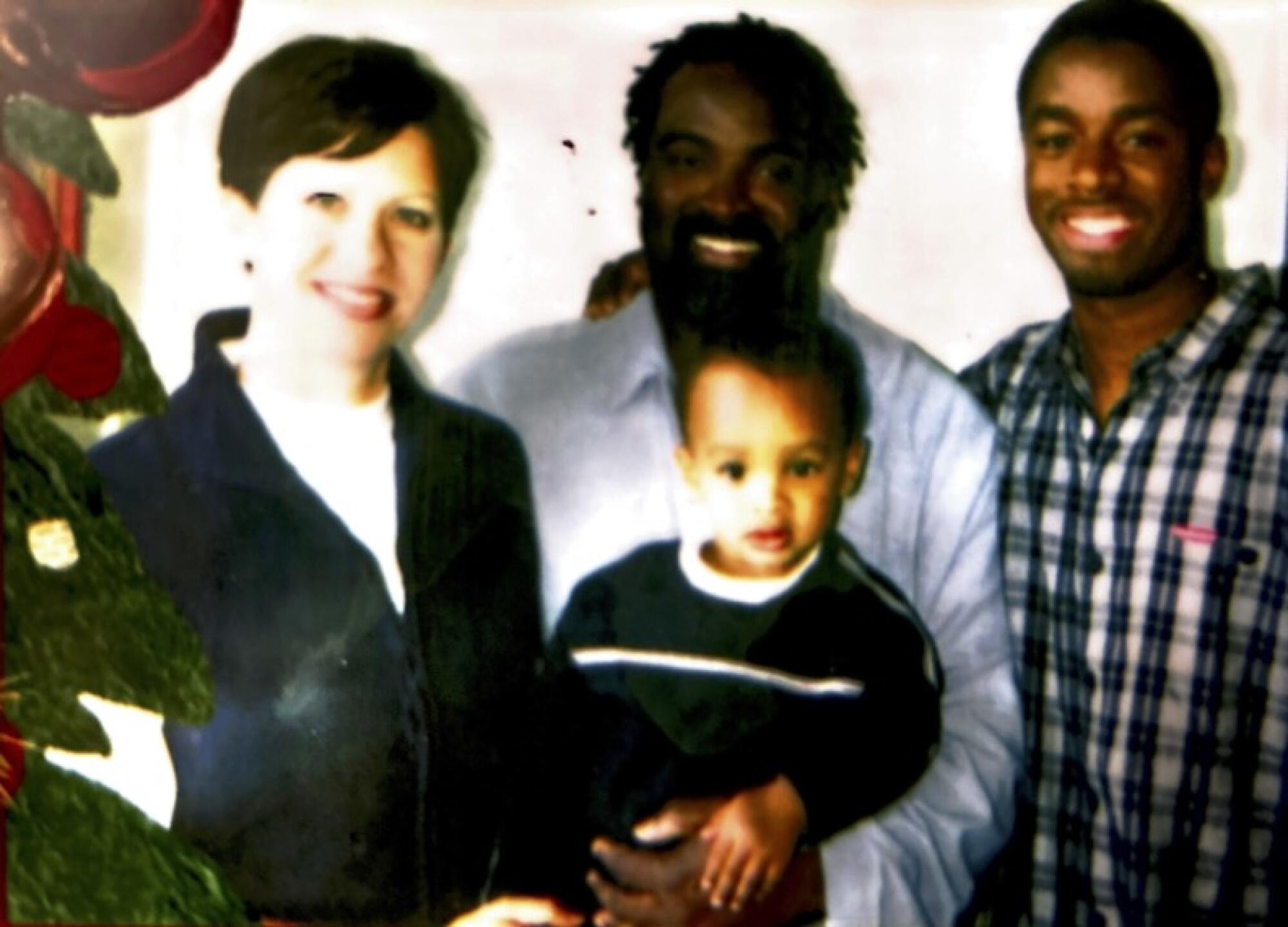

Wilson’s family may never know. But his descent into drug use, mental illness and crime is sadly familiar to them. His father, Stanley Wilson Sr., also played in the NFL but is known primarily for missing Super Bowl XXIII in 1989 after binging on crack cocaine the night before the game.

The Wilson family saga is of a father and son who shared tremendous athletic prowess, but faced monstrous personal demons.

Stanley Jr. was born Nov. 5, 1982. His parents were students at the University of Oklahoma, and the next day Stanley Sr. rushed for 143 yards in the Sooners’ 24-10 victory over Kansas State.

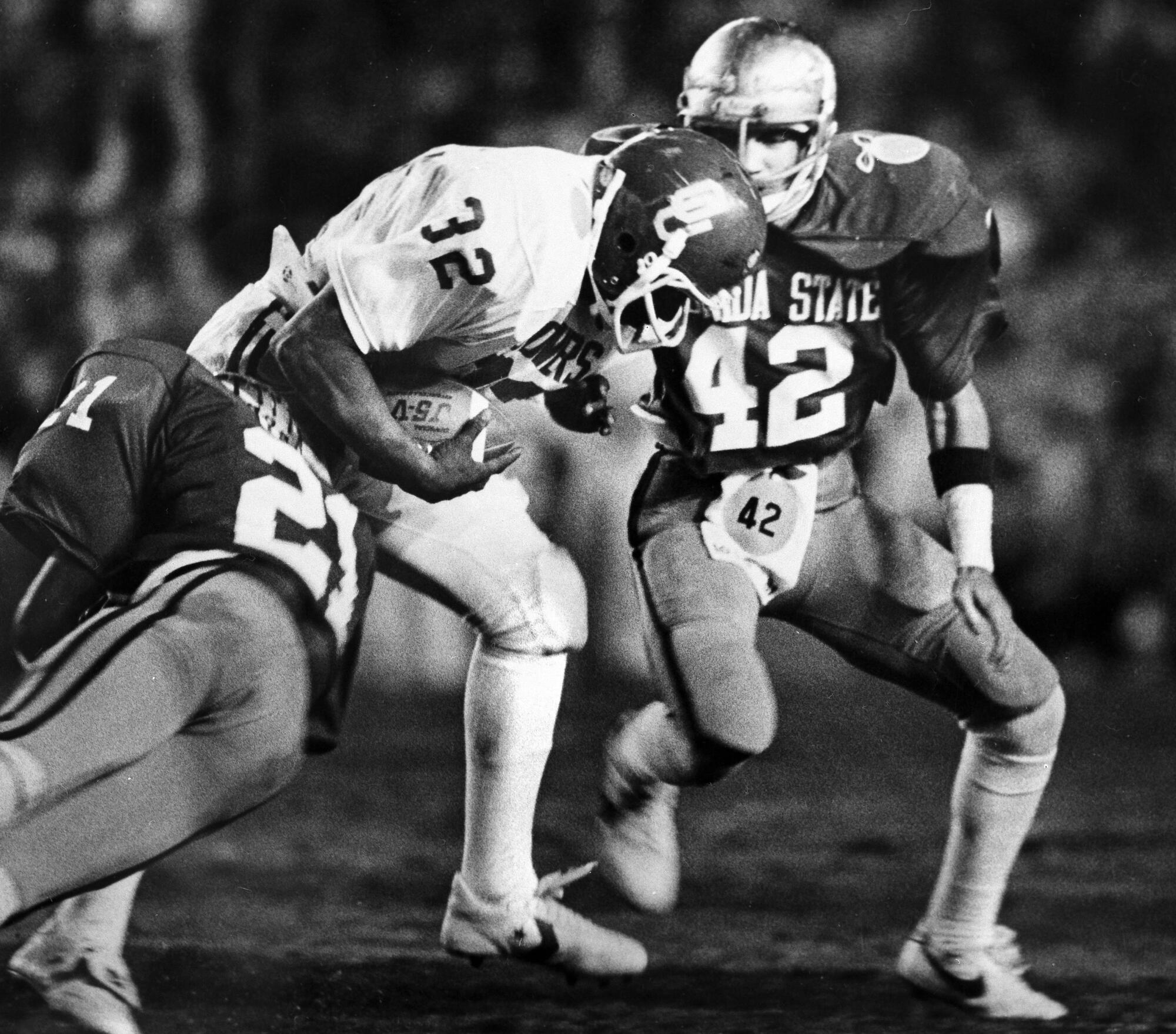

A few years earlier, he had been the L.A. City Section player of the year at Wilmington Banning High. At Oklahoma, he flourished — rushing for more than 1,000 yards in 1981. But college was also where he first tried cocaine.

The Cincinnati Bengals realized their rookie running back had an addiction problem soon after drafting him in 1983. They sent him to three rehab centers, but he relapsed in August 1984 and was suspended through the 1985 season. He played well in 1986 but was suspended a second time for the 1987 season.

The Bengals stuck with him, and he was key to the team’s 1988 run to the Super Bowl. Wilson Sr. hadn’t failed a drug test all season, but when a few teammates mentioned scoring some cocaine in the days before the game in Miami in January 1989, he couldn’t resist.

He smoked and snorted a large amount of cocaine and missed a team meeting the night before the game, and an assistant coach found him sitting in the bathroom of his hotel room in a cold sweat. Coach Sam Wyche cried while informing the team, and without Wilson the Bengals lost, 20-16, to the San Francisco 49ers.

Wilson Sr. had paid for his parents and 6-year-old son to fly from L.A. to Miami. He even rented a limousine to take them to the game. Wilson’s grandparents broke the news that his father wouldn’t be playing after all.

“My grandparents told me my father had gotten in trouble, and they asked me if I still wanted to go to the game,” Wilson told The Times in 2005. “I didn’t understand what was going on, and I told them I did. We went, and it was awkward. It was surreal.”

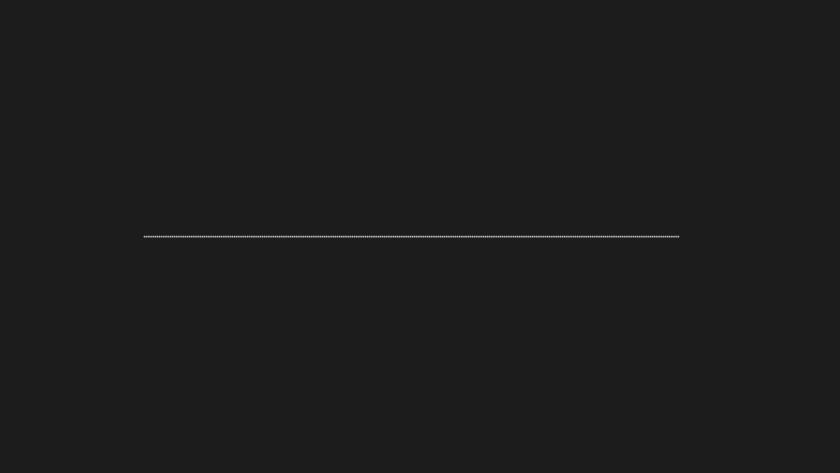

As a toddler, he had lived with his parents in Cincinnati until his father’s drug use led to a breakup. Wilson and his mother moved to Lucas’ hometown of Oakland, then to Cambridge, Mass., where he was a ballboy for the Harvard men’s basketball team while his mom pursued advanced degrees. She would earn three master’s degrees from Harvard. Lucas also received a Ph.D. in public policy and administration from Virginia Commonwealth University.

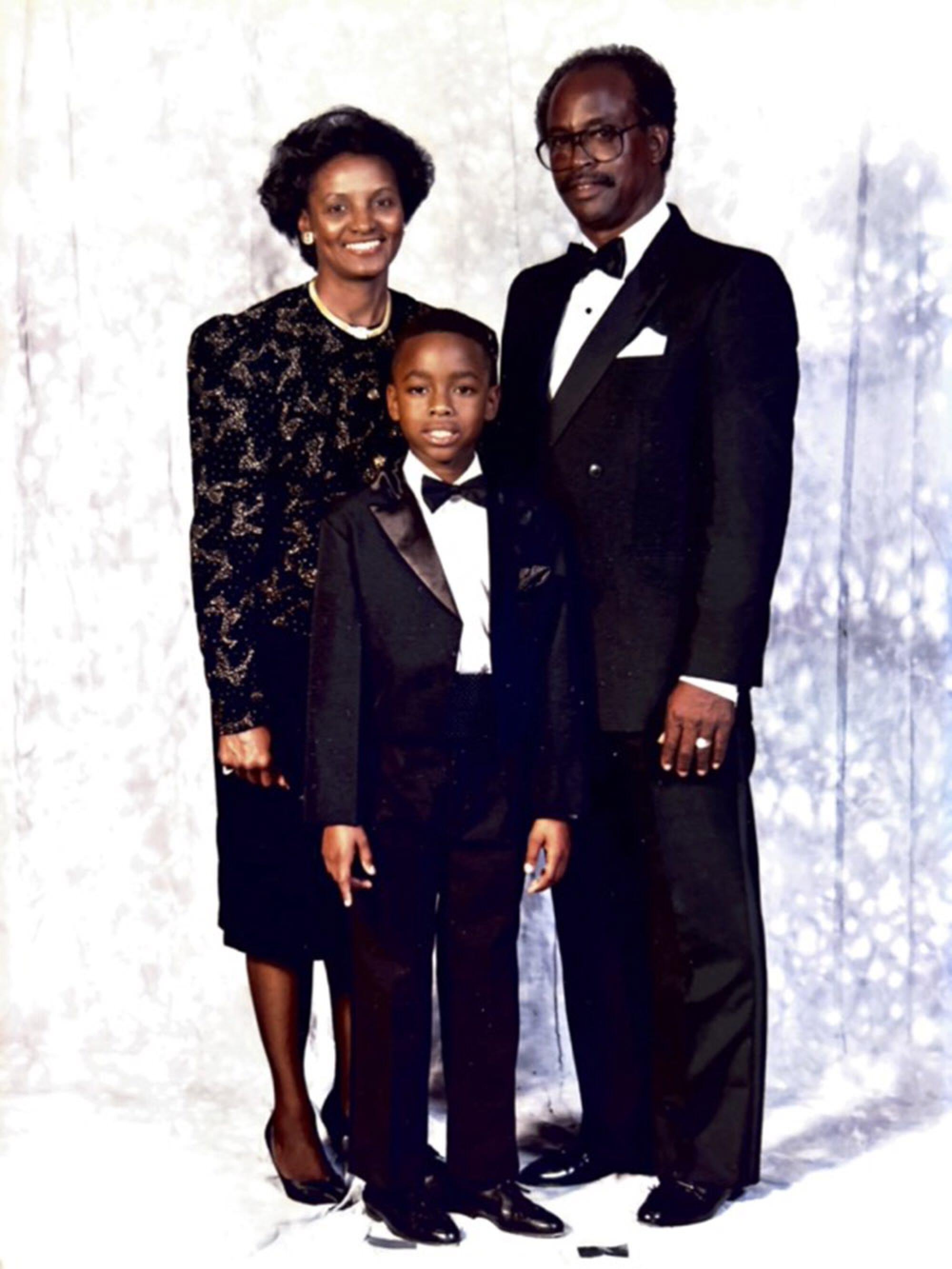

At age 6, Wilson returned to Southern California to live with his grandparents, Henry and Beverly Wilson, in the same house in Carson where his father grew up.

“He needed male role models, and I thought he’d be better off in a two-parent Christian home,” Lucas said.

At 12, Wilson told his mom he wanted to change his first name to Darren because whenever the Super Bowl rolled around, he was reminded of his father’s failings. “Every year he’d see something like the top-10 Super Bowl meltdowns, and kids at school could be mean,” Lucas said.

Wilson Sr. was mostly absent from his son’s life but surfaced as a volunteer assistant coach on his son’s 8-man football team in 1996, when Wilson was a high school freshman. Father and son were happy to spend time together, and Wilson Sr. had a chance to recount his own playing days, telling The Times back then, “That’s what is so neat about this, that I can sit down with him and go over my old videotapes and say, ‘Look, Stan, that’s your dad.’”

Wilson Sr. was struggling with long-term addiction, he openly says now, and suffered from psychotic episodes stemming from bipolar 1 disorder. He had turned to crime to feed his cocaine habit and, two years after reentering his son’s life, was sentenced to 17 years in state prison for burglarizing a Beverly Hills mansion, his third such arrest.

A sophomore at Bishop Montgomery High in Torrance, Wilson would visit his father at the prison in Lancaster and eventually became a mentor in a child visitation program, where he counseled others with incarcerated parents.

“He had a relationship with his father and I was happy about that,” Lucas said. “He was an African American young man, and I really wanted that for him. I wanted him to be in his grandfather’s presence as well.”

The boy once ashamed to be known as Stanley Wilson no longer wished to change his name.

“I think right about that time he really moved forward into football,” Lucas said. “I think his goal was to bring honor to the name Stanley T. Wilson.”

Stanley Wilson Jr. is an NFL prospect — and no one is happier about it than his dad, who’s in prison

Stanley Wilson Jr. is an NFL prospect, and no one is happier about it than his father, who has been in prison since 1999

That certainly was the case in 2005 when Wilson Sr. was six years into his sentence and Wilson was on the cusp of being drafted as a cornerback by the Detroit Lions.

“I’m happy to represent my dad,” Wilson Jr. told the Dallas Morning News that year. “It’s a blessing and a tribute to him that I’m here. A lot of people who might have a past like I do could have fallen by the wayside. The fact that I’m here today shows he’s a great dad.”

After playing at Stanford, Wilson was drafted by the Detroit Lions but lasted just three seasons. An Achilles tendon injury during the 2008 preseason forced his retirement.

Wilson, who had earned a bachelor’s in urban studies from Stanford, completed the NFL Business Management and Entrepreneurial Program at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania But over the next few years, Wilson drifted.

He considered becoming a doctor, then got a bachelor’s degree in nursing at Hunter College in New York. Like his father, Lucas said, he developed a drug addiction and began showing signs of bipolar disorder.

After his death, Wilson’s brain was found to show signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, the debilitating disorder common among football players and caused by repeated head trauma.

Lucas said she first became aware of her son’s deteriorating mental health in 2014, when a couple called her from New York City and said, “Your son gave me your phone number. We saw him walking down the street naked, but he was clean cut so we knew something was wrong. We took him to a hotel and paid for a room and we want you to know he’s OK.”

Stripping naked in public is occasionally a feature of bipolar 1 manic episodes, according to psychiatrists.

Wilson moved to Portland, Ore., and in June 2016 was arrested for climbing through a window into a mansion while naked — prompting the terrified 78-year-old homeowner to shoot him in the abdomen. When police arrived, Wilson was standing in a backyard water fountain cupping his wound.

He pleaded no contest to trespassing charges and to felony first-degree burglary for entering another home earlier that same day, making himself a drink and taking a book. Court records indicate Wilson also walked into or lurked in the yards of two other homes in the same upscale neighborhood while naked.

He was sentenced to 10 days in jail after telling the judge he was “happy to be alive.”

Lucas, who was living in Virginia, had near daily contact with Wilson by phone or text. She said that’s when he revealed that he’d been molested as a child by a male babysitter.

“I asked him, why are you going into these people’s homes? I don’t get it,” she said. “And he said, ‘I have to save the children from [molestation].’ Then I asked him, what is this, taking your clothes off and getting in these people’s fountains? He told me, ‘Mom, I have to cleanse my soul from what was done to me so that if I die I’ll go to heaven.”

A recording of a message Stanley Wilson Jr. left for his mother, Pulane Lucas, on Jan. 19, 2017, nine days after being arrested in Portland, Ore.

At the same time Wilson was having run-ins with the police, his father was released from prison. Wilson Sr. had spoken frequently with his son while incarcerated but had been unaware of the depth of his mental health and drug issues until the incidents in Portland.

“It came on like a whirlwind,” Wilson Sr. said.

In January 2017 while awaiting trial, Wilson was caught roaming naked in another neighborhood, according to a police report.

Over the next few years Wilson had periods of clarity. But as he tried to find work, frustrations mounted.

“He would wake up in the morning excited about a job interview and say, ‘Mom, I think this is going to happen.’” Lucas said. “He’d meet with them, and they’d say, ‘Oh, you have a felony,’ and that would crush him because … he was Stanford-educated and yet that felony prevented him, in his mind, from achieving the goals he’d set for himself.”

Wilson returned to Los Angeles, and things were relatively calm until October 2021 — when his 80-year-old grandmother, Beverly Wilson, filed a temporary restraining order request that stated: “After I retired for the night [Wilson] appeared outside my bedroom door in the nude with only a face mask on, with an iron on the hall floor, at which time he said he was heating the floor.”

Kevin Ellison was known for hard hits while playing for USC and the Chargers. Did that lead to increasingly bizarre behavior before his death?

The incident that sent Wilson to Twin Towers occurred Aug. 22, 2022. He broke into a $30-million Hollywood Hills home and bathed in a fountain with soap he’d found in the kitchen.

Two months after his arrest, the county Mental Health Division found him incompetent to stand trial on the burglary and felony vandalism charges.

Alarmed by his increasingly frequent psychotic breaks, Wilson’s parents initially were relieved that he had been incarcerated.

“Honestly, given Stanley’s behavior, I was happy to know he was in Twin Towers because I thought he’d be able to get help there,” Lucas said. “And we knew where he was. That brought us great comfort.”

Lucas was the last family member to visit Wilson in jail. She encouraged him to write his story to warn and inspire others.

“There are many people, many Black men who are going through what you have experienced,” she told him. “Your story will touch lives.”

On Nov. 7, 2022, the court ordered the Sheriff’s Department to transfer Wilson from Twin Towers to Metropolitan State Hospital by Dec. 5 and for the hospital to file a report on Wilson’s fitness to stand trial by Feb. 8, 2023. Wilson wasn’t transferred until Feb. 1.

Whether he was conscious during the move is unclear — the Sheriff’s Department has refused to share video of officers removing him from his cell.

Lucas and Wilson Sr. said county coroner investigator Justine Epperson told them their son died in his cell at Twin Towers. Later, they said, Epperson told them Wilson died after falling from a chair at Metropolitan State Hospital during the admission process.

Epperson did not respond to requests for comment.

A county spokesman provided The Times with the autopsy and an incident report compiled by Metropolitan State Hospital officials that includes interviews with the two sheriff’s deputies who transported Wilson from Twin Towers.

Deputy Katie Lowry stated that Wilson was not injured before or during the transport, that he did not complain of pain and that she did not see him ingest medication.

Angel Soto, the registered nurse who greeted the patients when the sheriff’s van arrived at Metropolitan, stated that she turned away from Wilson to take vital signs, and when she turned back, he had fallen from his chair and was “moving and breathing.”

Metropolitan State Hospital Police Officer Henry Moran said he witnessed Wilson get up from the chair, stumble and fall to the ground face-first.

Sheriff’s deputy Daniel Gutierrez said he rolled Wilson’s body over to remove his waist chain handcuffs and noticed his body was rigid “as if possibly having a seizure.” Moran said someone placed a pillow under Wilson’s head for support.

Soto said Wilson was breathing and had a pulse when paramedics arrived at 10:01 a.m. Four minutes later, an emergency medical technician began CPR and an automated external defibrillator was applied, according to the report. At 10:27 a.m. a doctor at the scene pronounced him dead.

The incident report written by Geneveve Ybarra, an officer at the hospital, concludes: “I find no evidence substantiating that Stanley Wilson’s death was the result of any criminal conduct (assault, neglect or abuse).”

Two autopsies, one by the L.A. County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner and one by a doctor hired by Wilson’s parents, concluded he died of a pulmonary thromboembolism — a sudden blockage of the blood vessels that send blood to the lungs.

An embolism usually occurs when a blood clot in the deep veins of a leg breaks off and travels to the lungs. There are several possible causes for this, but experts say blood clots can result from a person being held in restraints, unable to move.

Photos from the official autopsy — and those taken by an autopsy technician for the independent forensic pathologist — show an injury to Wilson’s forehead as well as red abrasions on his right hand and right knee. They also show ligature marks on his wrist from custodial restraints.

“It looks like he’s been in a violent encounter,” said Jason Major, the independent autopsy technician.

Major, who has assisted autopsies for more than 30 years, said he was surreptitiously shown the video of Wilson being taken from his cell at Twin Towers and that he appeared unconscious.

John C. Carpenter, a lawyer representing Wilson’s parents, contends in the lawsuit that his injuries and death were caused “as a result of excessive force used against him while he was in restraints and/or failure to provide ... care needed by him as a mentally incapacitated inmate.” A trial date is pending.

Jay D. Aronson, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University and an expert on in-custody deaths, advocates several reforms pertaining to in-custody deaths. One is that the definition includes the 24 hours after an inmate is released or transferred.

As Jay D. Aronson and Dr. Roger A. Mitchell explore in their recent book ‘Death in Custody,’ that lack of data is a national problem.

The Wilson case “is a classic story where the minute a person leaves a facility, the facility considers them no longer in custody,” Aronson said. “Nobody wants the death on their books.”

L.A. County spokesperson Jesus Ruiz declined to comment, citing the ongoing litigation. The Sheriff’s Department, in a statement to The Times, said only that Wilson had been released from Twin Towers and “while in the custody of the Metropolitan State Hospital he suffered a medical emergency and tragically passed away.”

I’m just a father and he’s my first born, he has my name. And ... nobody wants to tell me what the heck happened.

— Stanley Wilson Sr.

The hospital takes the opposite view. “Stanley Wilson had not completed the admissions process and was not a patient of Metropolitan State Hospital at the time of his death,” Ybarra wrote in the incident report.

The finger-pointing disappoints and angers Wilson’s parents.

“I’m just a father and he’s my first born, he has my name,” Wilson Sr. said. “And … nobody wants to tell me what the heck happened.”

And as they piece together their son’s last day, Wilson’s parents also reflect on his life — the great promise and his downward spiral. The drugs. The mental illness. The CTE.

After his death, Wilson’s brain was examined by Boston University researchers and shown to have Stage 1 CTE, the mildest of four levels of the disorder. According to the National Library of Medicine, a typical Stage 1 CTE patient may complain of mild short-term memory deficits and depressive symptoms, but is often asymptomatic.

Lucas chooses to reflect on the best versions of her son. He was a straight-A student, football star and homecoming king at Bishop Montgomery. Then came Stanford, the NFL and Wharton School. And he cared for family and friends.

“He never forgot birthdays,” she said. “He gave gifts. He enjoyed laughing. He loved watching Martin Lawrence movies. He loved dancing to Janet Jackson. He was just a wonderful boy and man, and we had a wonderful bond.”

Lucas also wonders if the molestation her son revealed contributed to his decline. She recently drafted a legislative proposal to expand parental rights in holding convicted child molesters accountable economically.

Wilson Sr, 62, lives in Wisconsin with his wife and two children. He says he is drug free and remains on anti-psychotic medication. “I’m more stable than I’ve ever been in my life,” he said.

His tale of achievement, humiliation, madness and incarceration is seemingly concluding with a measure of redemption. He laments that his son never got the same opportunity.

“When I was younger, there were times when I wasn’t receptive to even accepting the fact that I had mental illness,” he said. “Stanley had his moments where he was trying to get help, but he would crawl back into his cavern of darkness. I’m just sad he wasn’t given the chance to come out of that cavern. That was taken from him.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.