- Share via

Sometimes, you just know. You feel it deep in your gut. Not so much an instinct as an instant, unimpeachable sense of certainty so clear nothing could convince you otherwise.

That’s how Mori Sue’sue felt seeing Raleek Brown on a football field. He just knew. He knew before warmups of that first Little League All-Star tryout were finished. He knew by the way Brown moved at just 12 years old, so sudden and yet so smooth, deftly cutting on one dime after another, speeding past one … two … three … four unsuspecting defenders with ease. He knew the way those in Brown’s hometown of Stockton will tell you they’ve always known — at least since crowds started forming to see the young football phenom they once called “Mighty Mouse.”

Others who ushered Brown along the way, from the Southside Vikings all the way to USC, offer a similar explanation for how they came to believe Brown was bound for stardom. They just knew, they say — always with the same emphasis on the word.

At USC, teammates took all of a few days during preseason camp before treating the freshman’s bright future as a foregone conclusion. Eyes light up whenever they’re asked about Brown.

“It’s something I [saw] Day 1,” says USC receiver Tahj Washington.

“It amazes me,” adds Austin Jones, a fellow USC running back. “[I was] just sitting back in fall camp, like, ‘This dude is real.’”

“He was electric. You knew if he stayed the course, he was going to be a big-time player.”

— Clay Helton, on the impression a young Raleek Brown left on him

Until that tryout, Sue’sue had yet to hear much about him. But Brown’s father, Roscoe, was familiar with Sue’sue. His reputation in Northern California as a respected local seven-on-seven coach and talent evaluator preceded itself. So Roscoe approached him hoping he’d take a look at his son. He knew Sue’sue was working with Najee Harris. Before that, he trained Joe Mixon. Both would wind up as the No. 1 backs in their recruiting class, before becoming two of the best in the NFL.

Which is to say, Sue’sue knew a good running back when he saw one. “I haven’t missed on a kid yet,” he says.

And in the case of this particular kid, he was convinced. So much so that later that summer, he and his friend and fellow coach, Stuart Tua, sought to test the boundaries of Brown’s extraordinary talent.

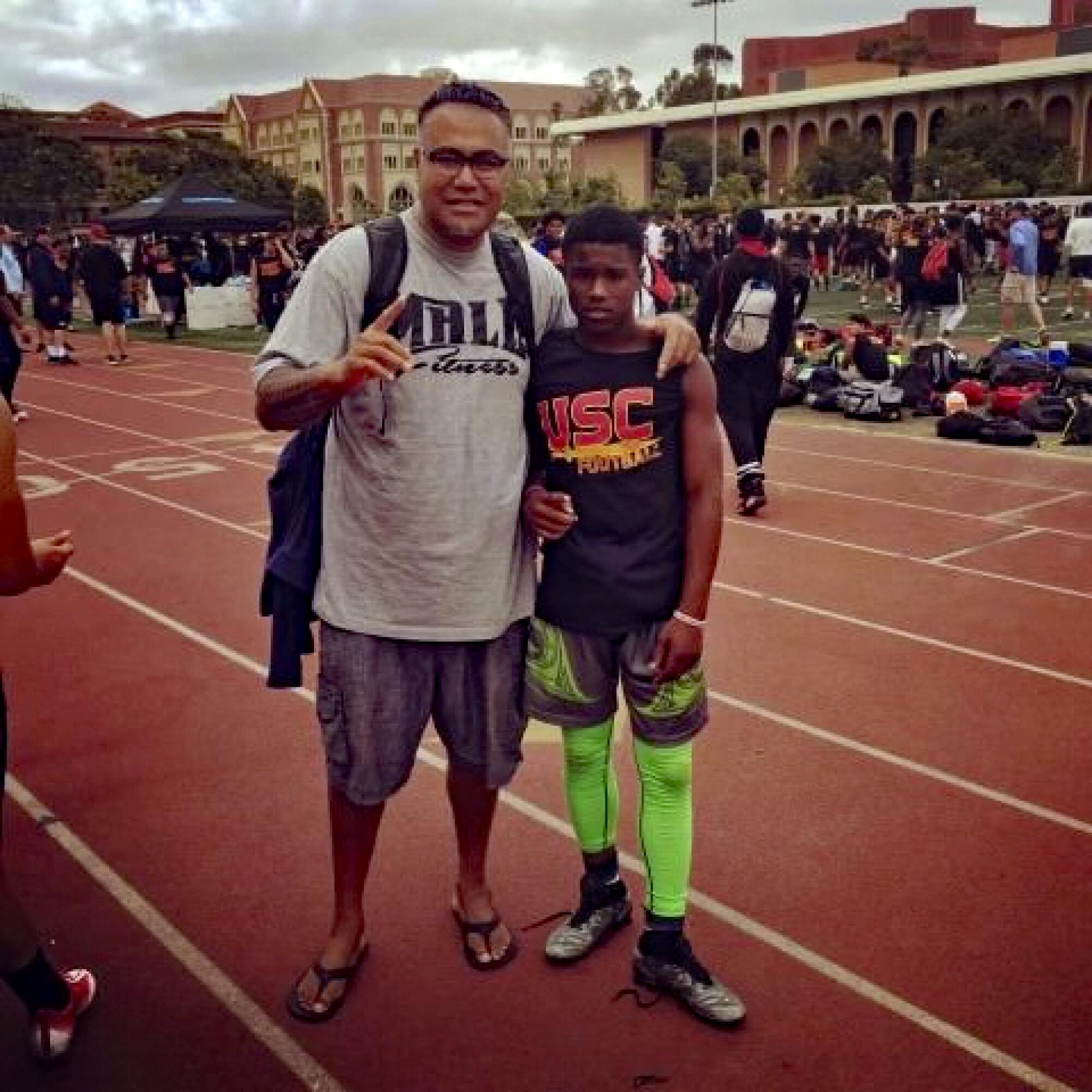

Six years before he struck the Heisman pose in the Coliseum end zone, boldly announcing his arrival during USC‘s 2022 season opener, the two coaches brought Brown to campus for one of the Trojans’ elite football camps. He was still just 12 years old. But the coaches say they were able to sneak him in, with the intent of testing him against several top high school prospects.

In a picture from that day, a smiling Sue’sue stands next to a pint-sized Brown, who couldn’t weigh much more than 100 pounds at the time. He’s wearing lime-green leggings, which stand out among the cardinal-and-gold throng on Cromwell Field and distract from the uncertain expression on Brown’s face.

It was a bold plan, but the two coaches say they were sure of the kid’s ability. They didn’t disclose to anyone he was still in grade school. Not until near the end of the camp, when Keary Colbert, a friend of theirs who was a USC assistant at the time, approached with news.

“KC comes over and tells us, ‘Hey, just to let you know, your kid is going to win the MVP for running backs at the camp,’ ” Sue’sue said. He chuckles thinking back. “Mind you, these are the best of the 10th-and 11th-graders.”

Hernández: Caleb Williams passed a modest test, but can he keep adapting to mask USC’s flaws?

USC quarterback Caleb Williams has delivered Heisman-worthy performances, but the Trojans’ success will depend on how he handles tougher tests.

“I laughed out loud,” Tua added. “There were some four- and five-star linebackers that he’d made look pretty silly. No one had any idea he was 12 years old.”

They fessed up to Colbert, who couldn’t believe it.

Brown didn’t officially win MVP that day … for obvious reasons. But his performance made believers of USC’s staff, which waited until the summer before he started high school to officially offer him a scholarship.

Years later, Clay Helton couldn’t recall many specifics from that one summer camp. But the former Trojan head coach still remembers the first impression the young running back made at USC.

“He was electric,” Helton told The Los Angeles Times via text message. “You knew if he stayed the course, he was going to be a big-time player.”

Talk to those around Brown, and they say they’ve always known he’s on the path to something extraordinary. And soon, they insist, everyone else will know too.

Roscoe Brown was sure his son would be special just watching Brown run around the yard as a toddler. He knew because, years ago, he’d been a sprinter at Edison High in Stockton, specializing in 100- and 200-meters. He understood speed. And his son, he soon learned, was a special kind of fast.

Those early assumptions were confirmed soon after Brown’s fourth birthday, when Roscoe first signed him up for flag football. In his competitive football debut, Roscoe recalls, Brown scored at least five touchdowns. He lasted just a single season in that league, before Roscoe moved him up to contact.

From then on, his father says, “we always had to move him a couple years ahead of his age group. He was just always ahead of his time.”

USC coach Lincoln Riley, known for his potent passing attack, unleashes the Trojans’ run game during a win over Fresno State Saturday at the Coliseum.

However far ahead he moved, Brown still seemed to sprint past expectations. Soon enough, they lost track of his touchdowns. In his second season of contact football, Roscoe estimates his 6-year-old son scored something like 72 times, but he can’t say for sure. The crowds started forming after that.

His pure speed seemed to translate at every level, so Roscoe trained him to harness it. He entered him into FBU football camps, starting in the fourth grade, just to challenge him. But eventually, it became clear his son needed additional guidance. So Roscoe sought out Sue’sue’s help.

“As soon as he saw Raleek touch the ball, it was a no-brainer,” Roscoe said. “He hasn’t left his side since.”

That summer, Sue’sue brought the young back to tryouts for his seven-on-seven team so Tua, his trusted fellow coach, could see Brown for himself.

“He’d just gotten done dominating high school kids. It was honestly dumb.”

— Mori Sue’sue, on Raleek Brown as a 12 year old

“It took basically two or three plays for me to realize, oh, this is the best back we’ve got,” Tua said. He surprised even Sue’sue by immediately elevating Brown to starting running back.

The decision upset some parents whose sons were starting running backs on their respective high school teams.

“So,” Tua explains, “I told them, ‘Let’s settle this right here.’ I brought Raleek out, and I had these two kids guard Raleek, then I had Raleek in turn guard them. Let’s just say the outcome was not good for them.”

They took him to USC’s campus a couple months later. Brown got his first Power Five offer, from Brigham Young, that summer, essentially on Sue’sue’s word alone.

Word soon started to trickle out about Brown. In the meantime, he had no choice but to return to Stockton Little League football.

“He’d just gotten done dominating high school kids,” Sue’sue said, with a laugh. “It was honestly dumb.”

Booker Guyton knew well before Brown’s arrival at Edison High he was a different type of talent than Stockton had seen in some time. Maybe ever. There were already YouTube highlight reels. “He was a folk hero by the time he was 8 years old,” Guyton says.

Curious, the Edison coach once invited the Pop Warner phenom and his father to a varsity practice. When he saw Brown on the sideline, he told him to throw on some cleats.

“The route he ran was so explosive and so abusive to the DB that I looked at his dad and told him, ‘Man, he could play varsity right now,’” Guyton says.

“He captured the community. People who didn’t even root for Edison were coming to watch football, you know, to watch this kid play. So when he left, it shook up our city.”

— Booker Guyton, on the impact Raleek Brown had at Edison High in Stockton, Calif.

No one was surprised when Brown took over immediately as a freshman at Edison and never looked back, racking up 2,429 total yards and 28 touchdowns. He was named MVP of the conference as a first-year running back. Brown made his presence felt in other ways, too, as Edison won its first league title in more than 40 years.

During his first high school game, Guyton recalls one play in which Brown caused a fumble on defense, only to turn around and lead the way as a blocker for a teammate, who returned the fumble for a score.

“Who does that as a ninth grader?” Guyton says. “You can’t coach that.”

Guyton told Roscoe he believed his son would put Edison “on the map.” But Brown was dominating with such ease that those closest to him wondered if he’d ever be challenged enough at Edison. He ultimately stayed as a sophomore and repeated as MVP, racking up 26 more touchdowns, which only deepened that sentiment.

Commentary: College football review: How Lincoln Riley’s hot USC start affects Nebraska, Urban Meyer

USC is being rewarded for chasing Lincoln Riley. Nebraska fans are envious of the Trojans’ rapid makeover, pushing them to overlook Urban Meyer’s flaws.

His decision to transfer wasn’t about football alone. Roscoe also worried about the violence and high crime rate in their hometown. “I didn’t want him around it no more,” he said.

Some in Stockton understood. Guyton admits he wasn’t one of them initially.

“He captured the community,” Guyton said. “People who didn’t even root for Edison were coming to watch football, you know, to watch this kid play. So when he left, it shook up our city. … But he wanted a bigger challenge, and he went and got that at Mater Dei.”

Bruce Rollinson had his own questions about how much competition Brown faced in his first two years. On tape, he was “dazzling,” the Santa Ana Mater Dei coach recalled. But would he really be that electrifying in the Trinity League?

He got his answer as soon as Mater Dei started seven-on-seven work.

“I gotta admit, I just went, ‘Whoa,’” Rollinson said. “I knew then this was a generational kid.”

Still, not everything came as easily for Brown at Mater Dei. Academically, the transition was a tough one. But he had a way of endearing himself to teachers, who often raved to Rollinson about Brown. There was energy about him that people gravitated toward.

For the first time, Brown also had to earn his place on a football field. Rollinson ran a far more rigorous, structured program than he’d ever experienced in Stockton. It took some adjusting.

“He was used to you know, drink a half-bottle of water, touch the toes a couple times and off I go,” Rollinson said.

Brown still had to learn some of the finer points of the position too.

“He’d never probably had to pass pro in his life,” Rollinson said, “and that was a project.”

The pandemic delayed his debut at Mater Dei to spring and nagging, soft-tissue injuries would follow him into summer. But the following fall, Brown wasted no time in making a statement. In his season debut as a senior, Brown ripped off a 78-yard touchdown run against Duncanville, a Texas prep powerhouse, on his first carry.

That season, as he solidified his place as one of the most coveted prospects in America, Rollinson lined him up all over the field. He often sent Brown into motion to exploit mismatches. Just the threat of his speed forced defenses to take notice wherever he lined up.

“He could take over a football game at any time,” Rollinson said.

But learning how and when to deploy him would be crucial, especially as the competition level increased.

Rollinson thinks back to the state semifinals last season against Corona Centennial. For most of the season, he’d been reluctant to use Brown as a workhorse. In five of 11 games, he saw fewer than 10 carries. But that night, Rollinson leaned on Brown entirely, handing him an uncharacteristic 27 carries, the most special of which saw him leap over a defender into the end zone. The touchdown — and his 158 yards — helped guide Mater Dei to the state final, and left Centennial coach Matt Logan screaming at the refs.

“I don’t think the officials even realized what he’d done,” Rollinson said. “They were trying to keep track of him, and he was just bouncing off people.”

Count Jalen Hurts as another person who knew right away. The current Philadelphia Eagles starting quarterback was convinced as soon as he saw Brown work out during an Oklahoma summer camp in 2019. The problem was the former Sooner’s realization came three years too soon.

“Jalen was hoping we could sign him then,” said Lincoln Riley, the former Oklahoma coach and current USC coach. “Jalen was disappointed when I told him he was a freshman in high school. To this day, Jalen still asks me about him.”

More have been asking about the Trojan freshman since his dynamic debut at USC two weeks ago. With just eight touches against Rice, Brown offered a memorable first glimpse of his tantalizing talent. But all it really took was one to know.

As soon as Brown took the handoff, the play appeared doomed. A Rice linebacker was well into the backfield, readying himself to take the running back down, when Brown threw out a stiff arm and shifted gears.

Suddenly, he was speeding past, a bewildered linebacker left in his dust. As Brown slid into the end zone for his first collegiate touchdown, he popped up quickly. Then, he struck the Heisman pose.

No one close to Brown was surprised by the bold pose. His USC teammates loved the gesture. “We was lit,” Washington said.

Roscoe beamed as he watched. Rollinson chuckled. Sue’sue shook his head, but had to smile. Everyone offered a version of the same response, when asked: “That’s just Raleek being Raleek,” they said through grins.

Brown has been slowed by an ankle injury, limiting him to five touches during the last two games, but it isn’t expected to hold him back for much longer.

As Roscoe watched his son score the first of what’s sure to be many touchdowns scored at USC, he knew the pose was more than that too.

It was an announcement.

“He’s telling everybody what he’s going for,” Roscoe said. “He ain’t here for nothin’ less.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.