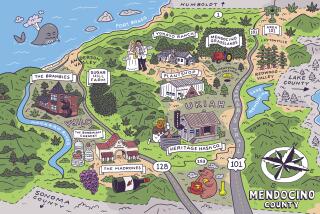

West Coast brewers pick up the distilling spirit

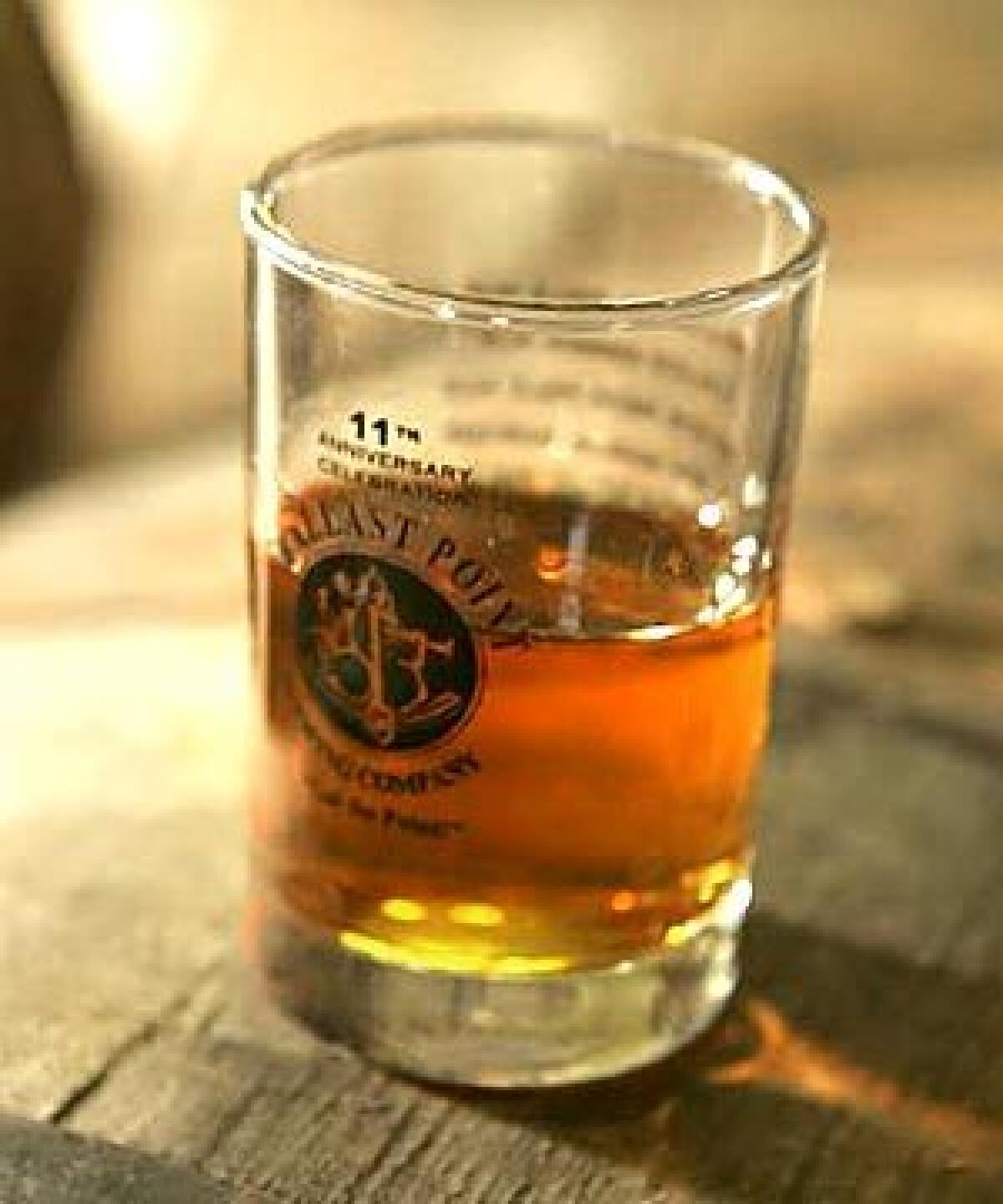

The half-dozen visitors gathered in Ballast Point Brewing’s tasting room bar are sipping Wahoo Wheat and Black Marlin Porter and dunking pretzels into a crock of bubbling house-made beer cheese.

Jack White, the 41-year-old owner of the San Diego brewery, refills the pretzel bowl and nods toward a large rectangular window behind the bar. He smiles like a proud father and offers a closer look at the new 600-square-foot distillery tucked inside the brewery.

“When we get them down, we’ll hit the market,” says White, referring to the rum and whiskey he’s planning to sell under the Ballast Point label.

In April, White and Yuseff Cherney, Ballast Point’s 38-year-old head brewer, installed the distillery in a small corner of the 11,000-square-foot brewery. So far, they haven’t conquered the brewing-to-distilling learning curve -- Cherney’s first batch of rum was a disappointment -- but they’re not giving up.

Ballast Point is one of a handful of craft breweries and former brewers on the West Coast, including pioneer Anchor Brewing in San Francisco and Sub Rosa Spirits in Dundee, Ore., that have taken up distilling. Like Ballast Point, these craft distillers started with a learn-by-doing approach, because aspiring distillers are forbidden by law from experimenting with spirits prior to opening a licensed distillery. (In contrast with beer brewers, who can experiment before they invest in a commercial facility -- provided the alcohol isn’t sold.)

“It’s a natural progression really -- brewing to distilling,” says Cherney, standing near a towering wall of cardboard boxes filled with empty beer bottles, one of the few areas of unoccupied space in the warehouse. “The alchemy of changing malt into beer is essentially one step away from making spirits. . . . Distilling is really a form of advanced brewing.”

Although there are food science degree programs at UC Davis and elsewhere that focus on brewing, Cherney, like many craft-brewery pros, perfected his beer-making technique as a home brewer. He and White met in 1992 when White, also a home brewer, opened a store called Home Brew Mart in San Diego. Cherney, a home brew instructor at UC San Diego’s extension program, was first a Brew Mart customer, then an employee.

When White opened Ballast Point Brewery in 1996, he offered Cherney the head brewing position. “He was a better brewer than I was,” White says.

The spirit of experimentation motivates White and Cherney, but the transition to making spirits involves a lot more red tape than the transition from home to professional brewing. Before distilling even a single batch, would-be producers must procure federal licenses and often-costly distilling equipment.

“You can’t just decide to make rum one day, try out a few flavors, like you can with beer,” Cherney says. “But I understand the fermentation process, so I knew I could figure it out when we got the distillery up and running.”

Parallel alchemies

THE SIMILARITIES between the making of beer and spirits are most apparent with whiskey. To make beer, crushed, sprouted barley is steeped and rinsed in a mash tun (large tank) to remove most of the sugars. Additional water is added and the liquid (known as wort) is fermented and briefly aged.

To make whiskey, the grain (typically barley, corn, rye or wheat) is steeped but not rinsed to preserve the residual sugars. The sugary liquid (called wash or distiller’s beer) is fermented and distilled (a process of heating the wash to vaporize the alcohol, then cooling it so the gas condenses and forms clear drops of distilled spirit).

Depending on the type of whiskey, the wash is distilled two or three times and barrel-aged for several years.

Cherney uses barley to make Ballast Point whiskey. “We’ve got a silo full of it out back already.”

To make rum, he begins with evaporated cane juice molasses and works with a different fermentation process, heating rather than cooling the tanks.

Cherney has focused first on distilling rum because it requires only a few months of aging as opposed to several years for whiskey. “We need something to sell now so we can afford to keep distilling.”

The decision to produce rum and whiskey was personal (both Cherney and White prefer them to other spirits) as much as it was practical. White says vodka didn’t have enough complexity, and making gin is less of a natural progression from brewing. “With gin, you’re adding herbs and flavors more on the back end, but with whiskey and rum, it’s more about how you use the stills and age them.”

But Cherney’s first batch of rum didn’t turn out.

“I never thought I’d have trouble coercing the yeast -- I do it all the time with beer,” he says, referring to the process of activating dry yeast with water and grain to initiate beer and whiskey fermentation. “But sugar fermentation is completely new to me.”

The 6-year-old American Distilling Institute in Hayward, Calif., offers seminars on the legal and logistical hurdles for aspiring distillers, and Cherney and White have each traveled to Kentucky twice in the last four years to study whiskey-making at conferences organized by the institute. But even at the five-day, $3,000 seminars in Kentucky, hands-on distilling by participants is forbidden by law.

Of the West Coast craft breweries that trod the brewing-to-distilling path before Ballast Point, Anchor Brewing was the first, releasing its original small-batch rye whiskey in 1996. Today, Anchor Distilling produces three varieties of whiskey and two gins, all re-creations of 18th and 19th century American-style spirits.

Rogue Spirits in Portland, Ore., a branch of Rogue Ales in Newport, produces nontraditional flavored spirits such as a rum made with toasted local hazelnuts and Madagascar vanilla beans.

In November, Michael Sherwood, founding director of the Oregon Brewers Guild, launched Sub Rosa Spirits in Dundee, Ore. Though he has yet to find a location for a distillery and so has not begun to produce spirits, he rents space at House Spirits in Portland. There he makes 100 cases per month of his saffron- and tarragon-infused vodkas (which aren’t distilled but are made by “polishing” Midwest grain ethanol through filtration, then infusing it with fresh herbs).

At the Ballast Point brewery, Cherney nods toward a laminated sign with “No beer beyond this point” in bold print and opens the chain-link metal door to the 600-square-foot cage in the corner of the warehouse.

“It might help with figuring out what’s going on with the rum if I could drink a beer in here,” he says, closing the door behind him.

Following the rules

FEDERAL regulations require a separate space for brewing and distilling, although the mash tun (the stainless steel tank used to steep grains in water) can be used for both. At some distilleries, such as Oregon’s Rogue, separate facilities differentiate the two (the brewery is in Newport, the distillery in Portland).

The Ballast Point distillery is simply the former staff lunch corner fenced off. Do the employees mind? “We built an air-conditioned lunchroom in our office, so they’re happy.”

Cherney assembled a hybrid still (neither a round pot nor a tall column) by re-purposing pieces and parts of equipment used for fermenting beer. In fact, he built every piece of distillery equipment except the 53-gallon Kentucky bourbon barrels.

Though he has a staff of more than 15 brewery employees, Cherney finds only an hour or two each week to “play around with distilling.”

In spite of the setback with his early efforts, Cherney isn’t worried. “We’re taking a more creative approach, coming up with something we like without the restraints of an established distillery that’s known for a certain style.”

“Good brewers are like good chefs. Once you’ve made something long enough, you don’t need a recipe, you just go on taste. Eventually I’ll end up with something I like.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.