Drop In, Tune Out

We’re like kids on Christmas.

Up before dawn, too excited to sleep, we tear into the huge canvas bags that have carried our flotilla of surfboards to the other side of the world. In the darkness, we rip off the bubble wrap and toss aside the beach towels we’ve used to cushion our toys on this three-day voyage to the remote reaches of western Indonesia.

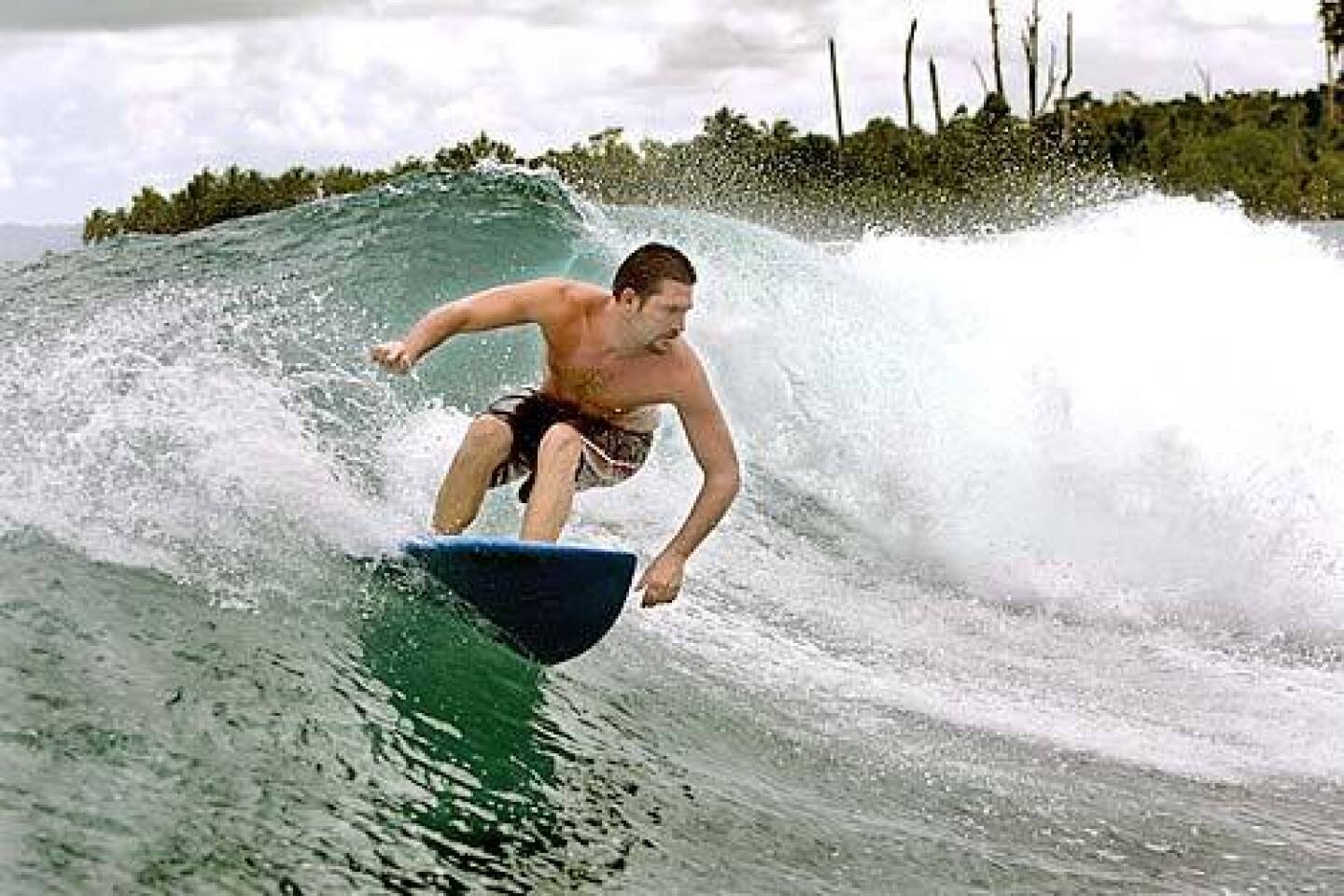

As the clouds lighten in hues of purple, we stand on the bow of our chartered yacht, awed by the outlines of a perfectly peeling wave. One by one, we plunge into the warm water of the Indian Ocean and stroke toward a surf break called Telescopes for the cylindrical shape of the swells.

Back home in Southern California, a place like this would be jammed with surfers jockeying for position. But at daybreak in the Mentawai Islands, we’re alone, a group of eight friends and relatives, slightly unsettled by the mystery of these new waters.

Within minutes, we will know why these exotic and primitive islands have emerged in the past decade as surfing’s premier destination. This archipelago off western Sumatra, with its four main islands and dozens of lush specks between them, boasts more high-quality breaks than even Hawaii. The waves are fast, powerful and treacherous, often crashing on shallow coral reefs. One spot is nicknamed the Surgeon’s Table because of its scalpel-sharp bottom.

The Mentawais are the final stop for storm swells generated near the tip of Africa, which roll unimpeded for thousands of miles across the Indian Ocean. With so many reefs hugging so many islands, waves can be found around virtually every bend.

The biggest names in pro surfing have anchored here—Kelly Slater, Andy Irons, Laird Hamilton and Layne Beachley. And then there’s us—three guys in their early 50s, one in his mid-30s, three in their 20s. Despite our varying ages, skills and stamina, we’ve come for the same reason as the sport’s elite: to take the measure of ourselves.

I married into something better than money. I married into a surfing family. My wife’s three brothers all grew up surfing in San Diego. Two of their sons, Brian and Michael Gable, have inherited the passion.

Like them, I started surfing in my early teens and never stopped. Even at 52, I find nothing washes away the troubles on land better than a few hours in the water. As most surfers will tell you, they get something more nourishing from the sport than just adrenaline.

It was last year, during a family vacation in Oceanside, when 27-year-old Brian popped the question. The kid I’d known since he was in grade school wanted me to go surfing with him and his 24-year-old cousin Michael in the Mentawai Islands (pronounced Men-Ta-Why).

If you say no, he warned, you’ll regret it forever. “Count me in,” I said, not betraying a hint of anxiety. But I was worried that, at my age, I might not be able to hold my own with all the young, ripping surfers who’d monopolize the waves. I’d be bummed in paradise.

Being an older surfer in a sport dominated by posturing 20-somethings is tricky. I’ve learned to turn my age to my advantage, making eye contact with everyone in the lineup and exchanging pleasantries. I want them to see me as a father figure—a cool father figure—so they’ll show respect by not “snaking” me, dropping into waves I’m already riding. In Southern California, that usually works. But in Indonesia, with the best of the best, I wasn’t so sure.

Now my two nephews—whose combined ages don’t equal mine—were yanking me into the surfing culture of their generation.

During the past half-dozen years, there’s been a revolution in surfing that, for the first time, is not about the length or shape of the board. It’s about place. As the sport’s popularity has brought more crowds to well-known breaks here and abroad, young surfers such as Brian and Michael increasingly are searching the globe for bigger and better waves they can ride in relative solitude.

Today, surf shops are filled with gear aimed at international travelers who rough it on faraway beaches, hole up in cheap hotels or penny-pinch for a year to charter boats. There’s a brisk trade in booties to protect your feet from the reefs, wax that won’t melt off the deck of your board in 80-degree tropical water and “board coffin” bags that hold multiple boards.

For the hollow waves of “Indo,” I filled my new bag with two new boards, including a “pocket rocket” designed for speed. Both cost me $1,000. Because the Mentawais are a malarial hotbed, surfers mostly bunk on rented boats, spending 24 hours a day afloat. And that meant even more money, beginning with a $500 deposit to a San Clemente-based charter company called Saraina Koat Mentawai. I was financially committed.

Then, six months before our trip, the tsunami struck, wiping out vast expanses of Indonesian coastline and giving me another reason to balk. In a preemptive e-mail designed to deter defections, Brian noted that the devastation was hundreds of miles north of the Mentawais and that our tourism dollars were desperately needed. Besides, he said, there might be fewer surfers and more waves for us.

“So are we still on?” Brian asked, and then supplied the answer: “HELL YES! There is NO backing out from the TRIP OF A LIFETIME!!!”

Still, it seemed unseemly to me to frolic in a region of so much suffering. So we decided to hash it out at Brian’s house in Orange County.

At evening’s end, Brian pulled out the final exhibit in his effort to keep the trip on track: a surf DVD called “The September Sessions,” filmed in the Mentawais. Sprawled on Brian’s living room carpet, we hooted and howled at the spectacular footage. Case closed. We were on our way.

As we converge on LAX in late May, we’re now eight strong. The four newcomers include 54-year-old Bobby Rickerson, his 27-year-old son and one of his classmates from a Northern California maritime college. Also on board is one of Michael’s friends, a 51-year-old investor nicknamed “Google” because he seems to have an answer for every question. And then there’s our freshest recruit, Times photographer Al Schaben, a 37-year-old Nebraska farm boy who began surfing 11 years ago when he moved to Huntington Beach.

Our flight from L.A. to Singapore is a back-aching 18 hours, with a brief stop in Tokyo. After a night of sleeping in chairs at Singapore’s Changi International Airport, we fly two more hours to the Sumatran port city of Padang, a colorful collage of chaotic traffic, dilapidated storefronts and sagging houses amid beautifully maintained mosques.

Our high-rise hotel, the Bumi Minang, looks as though it’s hosting a surfing convention. The floor of the ornate lobby is covered with clusters of board coffins that belong to surfers heading to or coming back from the Mentawais. The bellmen here need strong backs.

The next afternoon we arrive at a rickety pier on Padang’s coast. Carefree youngsters in T-shirts and shorts paddle in the murky water on old surfboards snapped in half. Beyond them, we see the yacht that’s been made available to us by a former salvage diver now recognized as the Christopher Columbus of surfing—Martin Daly of Australia. He pioneered surf charters in the Mentawais in the mid 1990s on a boat called the Indies Trader.

Ours is called the Adventure Komodo, a 75-foot-long twin-hull vessel with an expansive salon, full kitchen, flat-screen TV, surround-sound speakers and lots of other cushy comforts.

Originally we were booked on a more modest boat. But on its previous voyage, the air-conditioning quit and our charter company didn’t want to risk another snafu, especially with a reporter on board. Usually, Times travel writers remain anonymous on assignment. But in our case it would have been impossible to go undercover on the boat with one passenger scribbling quotes in a notebook and another lugging expensive camera gear.

Knowing what we were up to, Daly decided to give us a taste of luxury and of utility by putting us on two very different boats during the trip.

As we board the high-end Komodo, an Indonesian crew member hands us tropical smoothies and we collapse on the wraparound couches in the main cabin. We take a collective breath. After all the planning, the spending, the angst and the travel, we’re finally gazing at awesome islands, crowded with coconut palms and encircled by baby-blue waters.

On that first magical morning off the island of Sipora, as my nephews swap high-fives in the surf, I remember them in younger days. Although Brian’s appearance has changed little, Michael’s transformation is stunning. As a high school sophomore, he was 5 feet 9 and 210 pounds. “I didn’t like myself,” he says. “I didn’t feel comfortable in my own skin.” So he started surfing twice a day and became a gym rat. Now he’s 165 pounds of chiseled muscle.

And I, at last, feel more relaxed. I’m getting my share of waves as I surf at Telescopes alongside a lanky blond guy from Cardiff, Calif., who’s staying on another boat. He’s carving the deepest turns and shows more style than anyone. He’s not only graceful, he’s gracious. As a swell builds in front of us, he says simply: “This one’s for you.” I streak down the wave’s 5-foot face as the curl pitches over me—the complete union of surfer and sea.

That day, as in the days ahead, we surf until our arms are limp, drained of strength from paddling. Our chests, uncushioned by the wetsuits we wear at home, are rubbed raw by the wax on our boards.

For the most part, we hit the waves three times a day—at dawn, in the afternoon and always at sunset, when the clouds are streaked with orange and the ocean turns to amber. Between sessions, we feast on our chef’s latest concoction of meat or seafood, then read, watch surf DVDs or nap in our tiny two-person cabins.

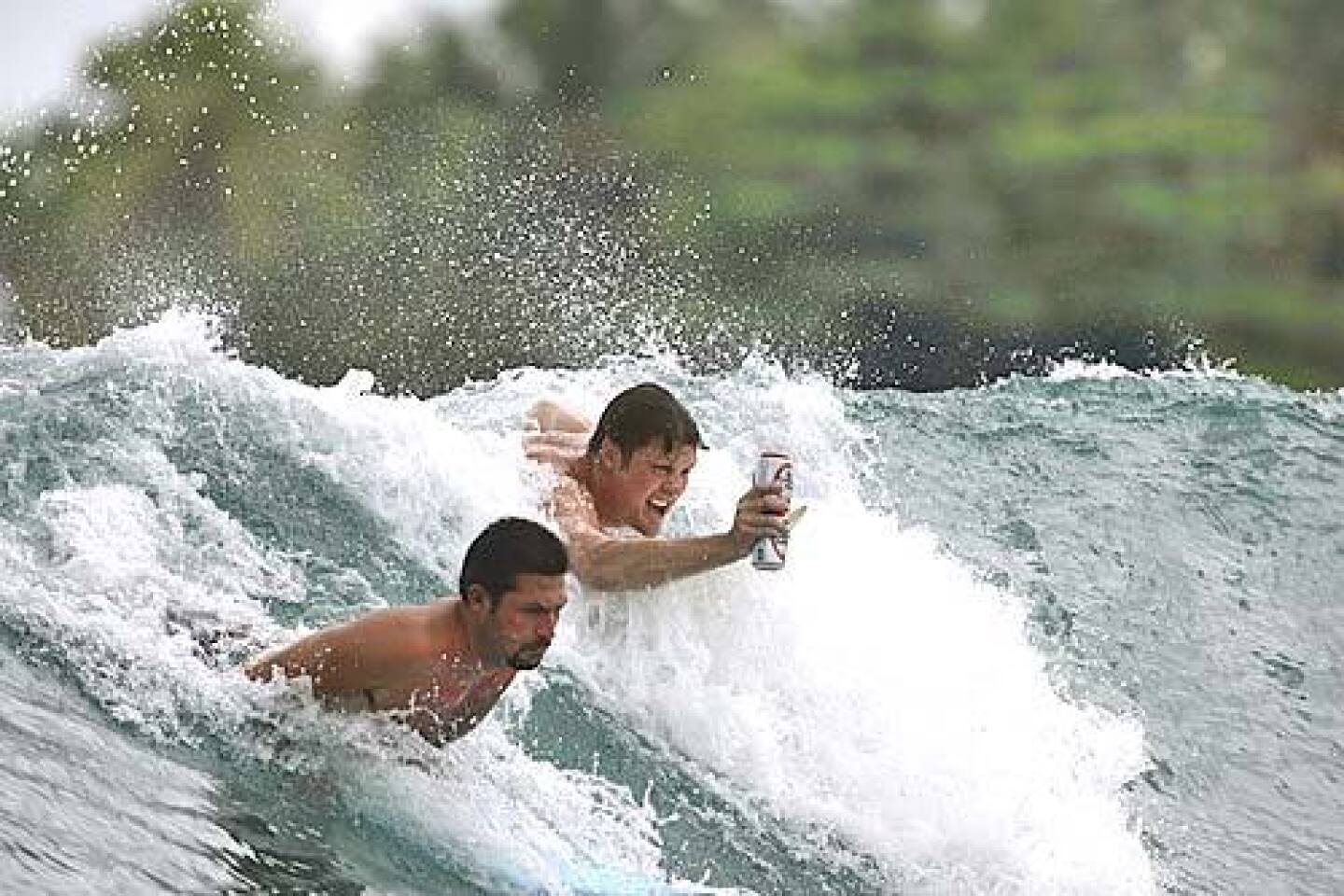

By midday, someone inevitably proclaims, “It’s Bintang time!” On the can of the popular Indonesian beer is the slogan: “Best Served With Friends.” Me, I stick with Fanta Strawberry.

After two days at Telescopes, we switch to Daly’s Indies Trader II, a vessel he’s described as “not as fancy as the other boats in the fleet but probably the best overall value for the hard-core surfer.” It’s like moving out of a boutique hotel to go camping. We’ve been spoiled, accustomed to being served smoothies every time we climb out of the water.

The only thing our new captain, Albert, seems to have in common with our departing one, Andy, is that they’re both Australian. Andy McCullough is polished and politic. Albert Taylor is intimidating. He has woolly blond hair, an ample belly scarred by surfboard fins and a weary look in his tanned, craggy face. He lays down the law: Dry off before entering the cabin, don’t mess with the air conditioning and flush the toilets properly.

With that, we’re headed south along Sipora’s coast to a place called Lance’s Left, several hours away.

Our disappointment over being bumped off the Komodo vanishes with one look at the waves. They’re barreling bigger than Telescopes and they’re empty—for the moment. The water is so clear we can see fish with yellow and black stripes beneath our boards.

That’s when we learn that we’re not just on any old boat now. The 70-foot Indies Trader II has ferried virtually every top surfer through these parts, including world champions Slater and Irons. And Albert, it turns out, has been skippering surf charters since the mid-1980s. He knows the Mentawais like the back of his sun-seared hand. He’s also softer than he looks.

“I like this boat,” the 43-year-old skipper says. “It’s simple. You can develop a relationship with it.”

But this is no dream job, he says, especially for a father of three young children who live with their mother in Sumatra. He’s at the helm 300 days a year, responsible for the safety of one group after the next. He says his exit strategy is hidden in the fertile Sumatran interior—a coffee plantation. He hopes to one day export enough beans to become a part-time skipper. For now, he hawks coffee to surfers on his boats.

At Lance’s Left, we encounter our first Mentawai islanders. Paddling from a sliver of sand, they soon surround our boat in canoes stacked with wooden trinkets, forming an open-water marketplace. We gesture with our hands because we don’t share a language. One man proudly holds up a plaque decorated with a curling wave. “Lance’s Leeft,” it says in big letters.

For most surfers, this is the extent of their interaction with the rural Mentawais’ 64,000 residents, who for thousands of years have lived mainly along rivers in the muddy jungles, hidden from the new nomads on yachts. Even today, elaborately tattooed shamans, or medicine men, hold sway over decisions in the settlements, where Muslims and Christians often live side by side in thatched dwellings. All are poor, many sick.

In 1999, a New Zealand surfer and doctor named Dave Jenkins was struck by the misery amid the beauty. Visiting surfers, he thought, should give something back to the Mentawai, so he founded several clinics to treat such preventable diseases as malaria, tetanus, measles and diarrhea. Today, with backing from corporate sponsors and professional surfers, Jenkins’ SurfAid International has outposts throughout tsunami-ravaged Indonesia.

Rising before dawn, Albert brews coffee in a French press and motors to another island, South Pagai, to a place where he knows he’ll find even bigger waves.

This break is called Thunders—for a reason. The waves here explode with a boom. On this day, the surf is about 10 feet high and scary.

Before leaving home, my one nod to my age and my familial responsibilities was to buy a surf helmet. I strap it on, even if I am flagging myself as a novice in surf of this intensity.

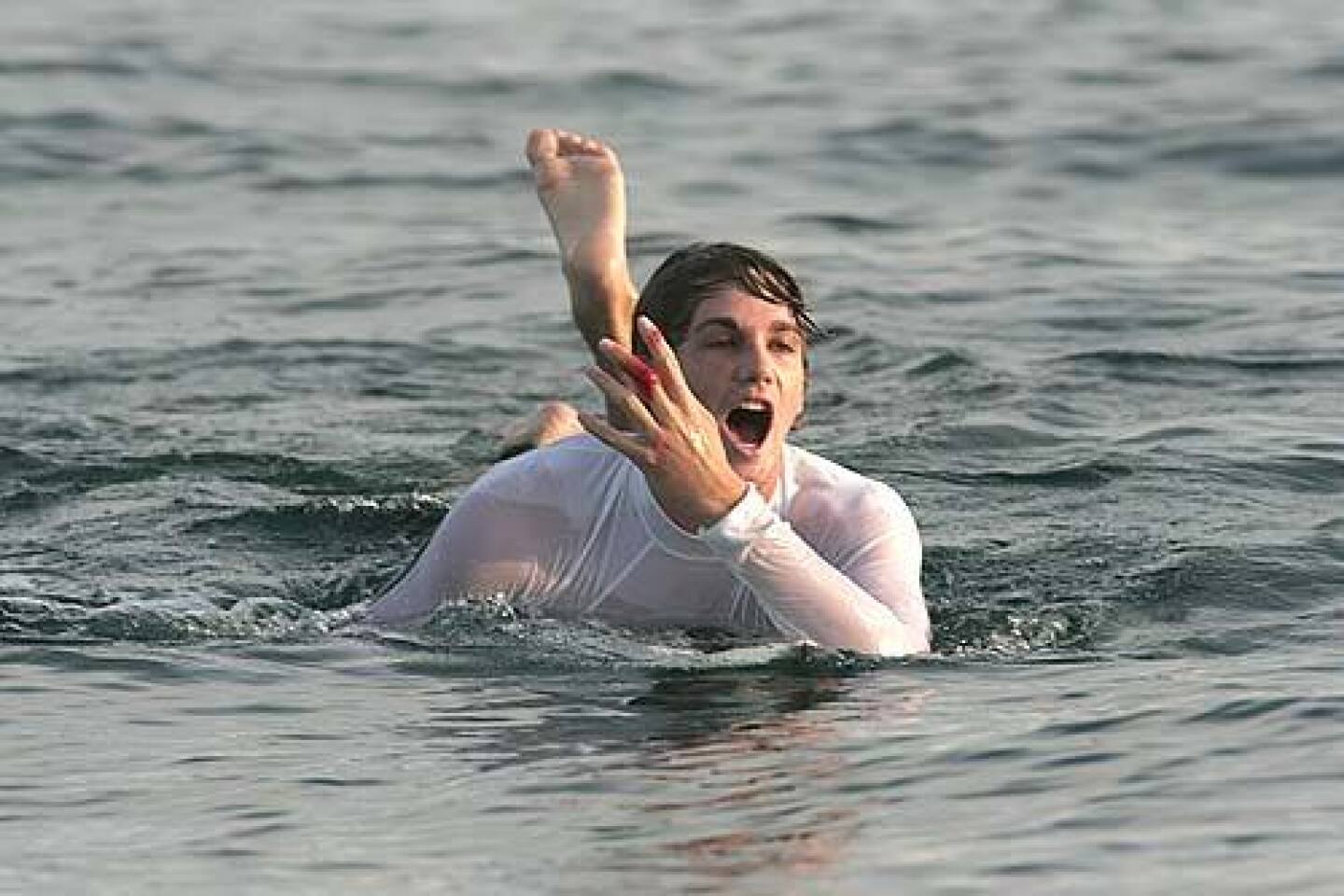

That morning, I streak down the fiercest, most punishing waves of my life. At least four times I think the end is near, as churning water pushes me down toward the lava rock and coral. Each time, I have one goal: Get to the surface and grab a single breath before getting yanked under again.

In our group, only Michael and Brian are out with me, riding some of the largest waves with the steepest drops. My attempts to match them push me beyond common sense. I emerge from the surf spent and mauled, with a nasty knot and a bruise on my chin where I was whacked by my board. But I’m also exhilarated, filled with a survivor’s sense of accomplishment.

“Never underestimate the Indian Ocean,” Albert warns me as I towel off.

That night, like every night, we enjoy our favorite ritual—photographer Al’s digital slide show. Since our first day, he’s spent hours in the tropical heat in a skiff near the impact zone, aiming his telephoto lens at us. His presence leads to one of the most commonly heard questions on the trip: “Dude, did you get that?” No one has ever photographed the likes of us.

Although Al’s a good surfer, he’s admittedly intimidated by the power of the Indo waves. For him, surfing is not about proving his mettle. “It’s not just about the waves,” he says. “It’s about what happens between the waves”—the lulls during which you can reflect on life. When he’s in the ocean back home, Al thinks mostly of an unborn son.

About five years ago, he and his wife, Susan, learned that their 5-month-old fetus was not developing a brain. With Susan’s health possibly endangered, they ended the pregnancy. “We spread the ashes at sea,” Al says. “I’ll sit on my board in the water and picture him riding a dolphin.”

Today, the couple have two rambunctious boys, ages 2 and 4. During our trip, Al runs up the biggest bill on the ship’s satellite phone, staying in close touch with his sons and wife.

One of the skipper Albert’s toughest challenges is to make sure all his passengers “get in their groove.” Because Thunders is too tough for some on the boat, he moves us to a couple of his special spots.

Although the surf is smaller, there’s not another charter boat in sight. Eight slender canoes, however, head our way while we’re anchored in a cove near an island with a village hidden behind tall foliage. They’re paddled by children in tattered clothes who appear to be no older than 10.

Forming a wedge at the back of our boat, they check out our surfboards, snorkeling gear and the video camera Al is using. Saying nothing, smiling little, the youngsters suddenly scamper aboard. Al shoots some footage and then replays it for them. They point at themselves in the viewfinder and laugh. Odds are they’ve never seen anything like this. Nor have we.

Some of the kids start doing back flips off the side of the boat. As Al teaches them how to breathe through a snorkel, the only grown-up among the islanders grabs my diving mask and jumps into the water fully dressed.

When the playfulness ends, they all row back to shore, where we see them riding ankle-high waves in their hand-carved canoes.

At that moment, I realize we have something joyous in common, transcending geography and culture. We’re feeling more in sync with the soft rhythms of their lives than with the demands of our own.

“What day is it?” someone asks over lunch.

“I think it’s Tuesday,” comes a reply.

“No, I think it’s Saturday,” another chimes in.

It seems more like home when we drop anchor near the coast of North Pagai at the most famous surf spot in the Mentawai chain—Macaronis. There are six boats anchored nearby.

“I’ve never seen this many people here,” Albert says in disgust.

In all, 40 boats are hunting waves in the Mentawai Islands, with about 2,000-plus surfers making the journey during the dry season between late April and early November.

The skipper’s even unhappier about what he sees near the beach—a new eight-villa development called Macaronis Surf Resort. For Mentawai veterans such as Albert, who’ve experienced many solitary days in these waves, this and another new land-based development, Kandui Resort, are dark clouds on the horizon.

Kandui is the brainstorm of two 30-year-old surfing entrepreneurs, Jordan Heuer and Anthony Marcotti, the latter a fifth-grade teacher who arranged our trip through his San Clemente travel company. The two pooled their savings to buy the land through an Indonesian partner and raised $700,000 more, mostly from Hawaiian investors, to build eight bungalows and the infrastructure to support them.

When the place opens next spring, Marcotti says, it will cater to spouses of surfers by offering cultural excursions, snorkeling, satellite television and wireless connections. There also will be video cameras trained on the great breaks nearby, to which surfers can be whisked by speedboats.

Marcotti questions the sincerity of boat operators who complain about excessive commercialization. His resort and the others in the works, he says, will give an economic lift to the impoverished locals and that the islands are too remote to become overrun by tourists.

“These old guys want to protect their interests,” he says. “Surfing has already changed the character of the place.”

Christmas is over.

As Albert heads out across the Strait of Mentawai for our nightlong journey back to Padang, we quietly begin to rewrap our toys. We’re all business now, efficient and organized—except those of us who can’t remember where we put our shoes. We’ve been barefoot for nearly two weeks.

We eat a final meal of pan-fried steaks with roasted potatoes and shiitake mushrooms, prepared by our chef, 28-year-old Ben Haight, an accomplished surfer himself. After us, he says, he’s on-call to cook for Laird Hamilton, the most renowned big-wave rider.

For the most part, Ben says, the pros come here to work. “They don’t party, drink, stay up late. They’re as boring as a bedsheet. Most of the time they watch DVDs of themselves in their cabins.”

Not us, he says. “You guys got your stoke on.”

Late in the evening, as we party and reminisce, the skipper suddenly throttles down the boat. Indo is imparting a final reminder of its power. This one comes not from the sea but from the sky—the hardest rainfall any of us have ever seen.

“To the bow!” someone yells. Bare-chested, wearing only board shorts, we’re pelted so hard that we can tolerate the pain for only a few minutes before defying one of the captain’s rules—dashing into the cabin drenched and dripping.

Above the laughter, someone again screams: “To the bow!” And so it goes for almost an hour as we test ourselves against the elements one last time. Our 10 days here have made us feel stronger, inside and out.

The adventure also has changed me in a deeper, more unexpected way, as I learn the weekend after our return when I go surfing with my 15-year-old son, Jesse. I’ve come back from the Mentawai Islands not only with great memories but also with a new perspective on the surfing life.

The water at Huntington Beach that day is dirty, cold and crowded. The waves are poorly shaped, about head-high. Before the trip, I would have paddled madly for as many of them as I could. This time, I calmly stroke beyond the masses and patiently wait for the best swells to roll in, remembering some wisdom Albert offered one day as he watched me struggling to position myself at Thunders.

Sitting on his surfboard, he looked over his shoulder at me and said, “Let the waves come to you.”

For additional photographs, go to https://www.latimes.com .

GUIDEBOOK

Getting on Board

Telephone numbers: The country code for Indonesia is 62.

Getting there: From LAX to Padang, Indonesia, connecting flights (change of plane) are offered on Singapore, United and Cathay Pacific airlines.

Surf tours: The following companies offer charter packages for surfing in the Mentawai Islands. I used boat broker Anthony Marcotti, who works for San Clemente-based Saraina Koat Mentawai, (714) 369-8121, https://www.mentawaiislands.com , and Indies Trader Marine Adventures, (877) 808-0813, https://www.indiestrader.com . Both offer packages on numerous boats. Prices include transportation from Padang airport, full crew, meals and beverages, including beer, for 12 full days of surfing. For the Adventure Komodo: $4,444 per person, based on nine passengers, or about $370 a day. For the Indies Trader II: $3,333 per person, based on nine passengers, or about $270 a day.

Other popular charter services include Wavehunters Surf Travel, (888) 899 8823, https://www.wavehunters.com ; and WaterWays Surf Adventures, (888) 669-7873, https://www.waterwaystravel.com .

Lodging: In Padang, Hotel Bumi Minang, Jalan Bundo Kandung 20-28; 751-37555, https://www.bumiminang.com . Doubles about $60.

For more information: To learn more about the history and culture of the islands, A visa is needed to visit Indonesia. Contact the Embassy of Indonesia, 2020 Massachusetts Ave. N.W., Washington, D.C., 20036; (202) 775-5200, https://www.embassyofindonesia.org .The State Department warns U.S. citizens to defer all nonessential travel to Indonesia. Americans who travel there should “observe vigilant personal security precautions and remain aware of the continued potential for terrorist attacks.” For more information see travel.state.gov.

-- Joel Sappell is a Times assistant managing editorMore to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.