To Bodega Bay, for the birds

- Share via

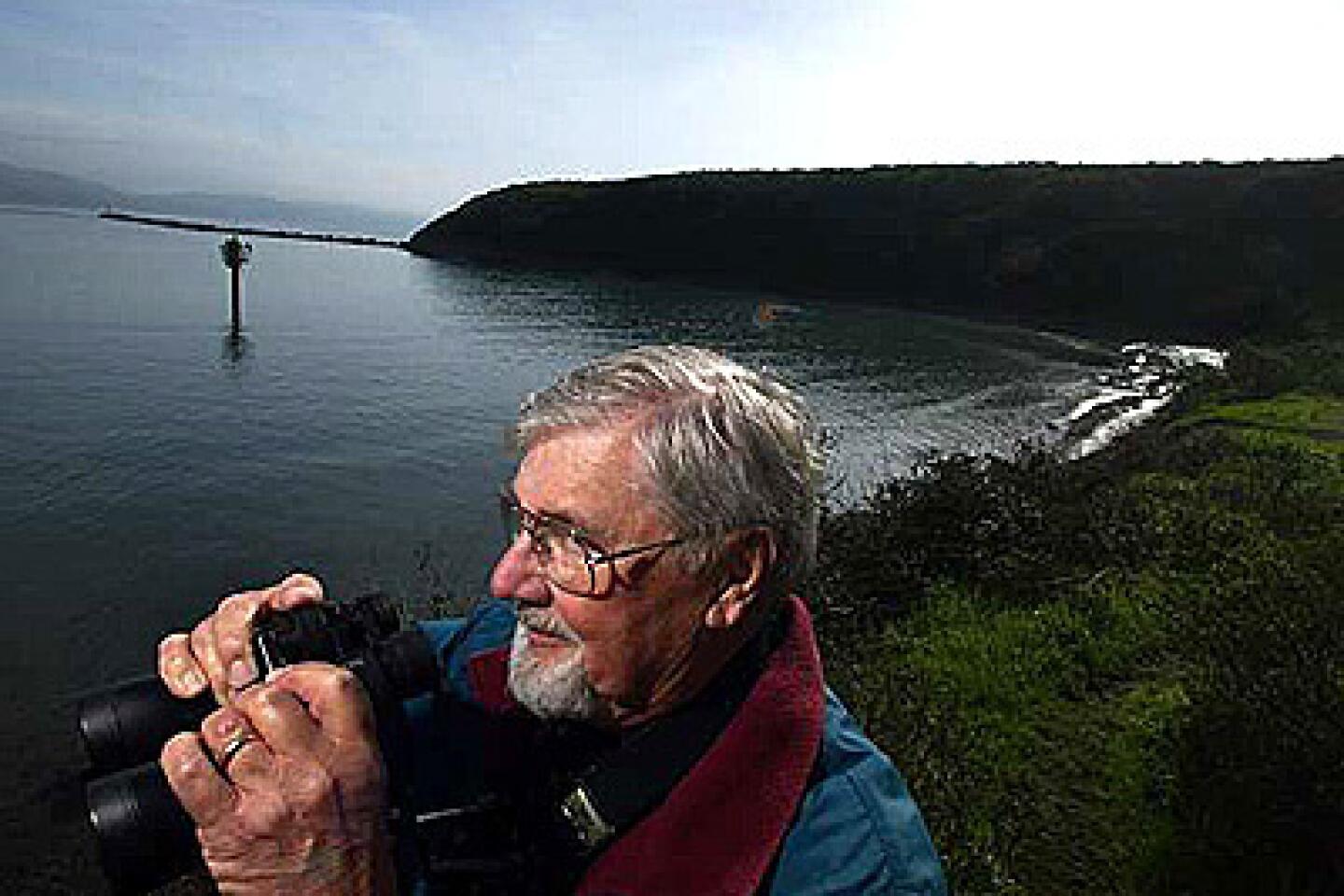

Bodega Bay — No, there’s never been a fatal bird attack on visitors to this picturesque fishing village an hour’s drive north of San Francisco. “Not a one,” said local birder Ken Wilson, who is amazed at the hold that Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller “The Birds” -- filmed here and nearby -- still has on people 40 years after its release.

And Blake Drescher at the Bodega Bay Visitors Center says, “Thirty percent of our visitors ask, ‘Where are the Hitchcock landmarks?’ It’s a phenomenon. We even have teenagers coming in wanting to see the sites.”

In the gift shop at the Tides Wharf & Restaurant -- which was remodeled in 1997 and barely resembles the one featured in the film -- you can buy a menacing-looking faux crow ($20) or a light switch cover with the likeness of “Birds” star Tippi Hedren and this warning: “The Birds are out there! They are sure to be about when the lights go out.”

The birds are out there, all right, but they aren’t the evil creatures of Hitchcock’s film.

Bodega Bay, permanent population about 1,000, is one of North America’s best birding spots, for the last decade in the top 13 in number of species sighted by more than 1,800 reporting National Audubon Society affiliates. Last year’s annual Christmas count turned up 173 species, including egrets, herons, hawks and pelicans. The significant numbers of endangered or declining species such as the snowy plover, black oystercatcher and long-billed curlew, and concentrations of breeding, migrant and wintering birds, place Bodega Bay among the American Bird Conservancy’s 500 “globally important bird areas.”

Bird-watching is a year-round activity in Bodega Bay, with migrating shorebirds and Eastern land birds coming and going and species such as white-crowned sparrows and pelagic cormorants nesting. This time of year is perfect for seeing shorebirds -- if you can hit town between storms. When it rains, the dedicated bird from their cars.

Wilson, a landscaper who takes birders to exotic foreign locales on his Talon Tours, calls Bodega Bay “one of the best places there is. You’ve got the ocean, the bay, fresh water and hillsides all around with native brush, lots of different habitats. A lot of migrant waterfowl spend the winter waiting to go back to Alaska.”

For those whose idea of a good time is not peering through binoculars, Bodega Bay is in itself a pleasant destination, well situated for forays into quaint towns nearby and an easy drive to Sonoma and Napa vineyards. And if you’re in no rush, getting there is half the fun.

On a recent Monday, I flew into Oakland, picked up a car and drove north to Marin County, taking the Highway 1 turnoff to Stinson Beach. The two-lane road winds along the coast with glorious ocean views, bucolic landscapes and, on a gray winter day, hardly another car during my 2 1/2-hour drive.

As I checked into the Bodega Bay Lodge & Spa, a complex of two-story wood-shingled buildings, a fire was crackling in the lobby’s massive stone fireplace and the complimentary daily wine hour was underway. I’d booked a bargain ($129 on Expedia.com for an ocean-view room with king bed and fireplace; the brochure rate is $240 on weekdays) and was upgraded to an even larger room because of potential noise: Some hotel refurbishing was in progress.

The next morning began with continental breakfast in the Den, a cozy room off the lobby. The lodge supplies bird books and binoculars on request.

Driving north through town on Highway 1, I turned left at the community center to the Children’s Bell Tower, a monument to Nicholas Green, the 7-year-old Bodega Bay boy killed by robbers while vacationing with his family in Italy in 1994. An 18-foot tower, moving in its simplicity, is reached by a footpath through an open field. From it hang school bells, church bells, cowbells -- sent from all over Italy to thank the Greens for donating their son’s organs to help make a difference in seven Italian lives. The center bell bears Nicholas’ name and those of the recipients.

Continuing north, I stopped at turnouts to watch the waves crashing against dramatic rock formations on the beaches below. Inland, cattle and sheep grazed on a green and gold landscape. This is the Sonoma Coast, only an hour or so north of San Francisco by freeway yet largely unspoiled, a place of solitude and hauntingly wild beauty.

In 30 minutes I was crossing the Russian River and turning east onto Route 116, a scenic highway that hugs the river and its heavily wooded banks.

Soon I was in Duncans Mills, population 85, where hot coffee at the Gold Coast bakery fortified me for a walk through the restored town with its 19th century storefronts. Near here, in 1877, notorious poet-bandit “Black Bart” -- Charles E. Boles -- held up a Wells Fargo coach. He was wearing, as usual, a white-linen duster, a flour sack over his head and a derby atop it.

More on the menu

Those coming to Bodega Bay to follow in Hitchcock’s footsteps may be disappointed. The only major film site still standing is the 1873 Potter Schoolhouse, where that flock of crazed crows attacked the children. And it’s in the town of Bodega, inland five miles south. The two-story white clapboard is now a private home, open four afternoons by appointment.

The town of Bodega has a bar, an antiques store or two (which were always closed) and the Artisans’ Co-op, with jewelry, pottery and very nice hand knits, all made locally. I knew I was no longer in Los Angeles when I found myself totally alone inside for 10 minutes. The woman in charge was next door chatting with the dressmaker.

Bodega Bay is no gourmet’s paradise, but the Duck Club, the restaurant at the Bodega Bay Lodge & Spa, claims “the best food north of San Francisco,” and it is very good indeed. The room is welcoming, with candlelight and a stone fireplace. Halibut with a sauce of puréed roasted yellow peppers, ginger and pineapple on a bed of basmati rice was delicious, as was the crème brûlée, and the staff was attentive.

For hearty breakfasts, locals like the Sandpiper at adjacent Porto Bodega, where there’s a sportfishing marina. It’s an unpretentious place with knotty pine paneling, vinyl tablecloths and indoor-outdoor carpeting. At a nearby wharf where fishing boats bring in their catch you can buy salmon, prawns and live Dungeness crabs.

The Tides Wharf & Restaurant on Highway 1 all but screams “tour buses” but has great harbor views, a restaurant and gift shop and a fish market selling liquor, sundries and fancy foods. Across the highway, the Bay View restaurant at the Inn at the Tides serves “filet mignon Hitchcock” with Dungeness crab and béarnaise sauce. (A nice touch, although a former Tides waitress has been quoted as saying the rotund Hitchcock always ordered filet of sole and green beans.)

Bodega Bay is not a pedestrian-friendly destination. The town wraps around Bodega Harbor, but most lodgings and restaurants are right along Highway 1. Tourist venues are limited; the real attractions are the coastline and the fishing village ambience. The bayfront Bodega Harbour housing development has a seaside Robert Trent Jones Jr. public golf course. There are a few art galleries, a kite shop and the delightful little Gourmet au Bay selling wines and accessories, whimsical pottery and handblown glass.

Wil’s Fishing Adventures offers whale watching from December through March, crabbing trips from November through May and salmon fishing excursions from April through September. Bodega Bay Kayaks has kayak and bike rentals year-round.

One day I drove inland through Bodega, taking a left turn to Occidental and stopping in little Freestone, home to Osmosis, a spa noted for its Japanese enzyme bath, in which one is immersed in a wood tub filled with hot, fermenting cedar fibers, rice bran and the like.

According to local lore, the proliferation of spas in Sonoma County can be traced to Samuel Brannan, a settler who in 1846 saw the potential for Northern California, with its natural springs, to be the Saratoga Springs of the West. Having become rich selling supplies to prospectors, he began buying land and, in an inebriated moment, proclaimed his intention to create “the Calistoga of Sarafornia.” A town was named.

The tree-shaded road past Freestone leads to Occidental, where there is bird-watching of a different kind. A self-assured rooster -- truly the cock of the walk -- struts past the shops. A shopkeeper told me that the bird -- known to some as “Mr. Mayor” -- fell from a truck about a year ago and was adopted by the town. Occidental has steepled churches, Italian restaurants, a Victorian B&B and worth-a-look gift shops.

Through the binoculars

On my last day in Bodega Bay I had a date with three members of the Madrone Audubon Society of Sonoma County. Our group included Lewis Edmondson, a retired Food and Drug Administration inspector; Claire Shurvinton, a British-born community college biology teacher; and Betty Burridge, a retired physical therapist. They arrived with telescopes and spare binoculars.

It was the kind of gray day that Hitchcock had hoped for, wanting to depict Bodega Bay as gloomy and forbidding. But he hit a sunny spell, and the gloom had to be added in the film lab.

We drove toward Doran Park Beach, which separates the harbor and the bay, and within minutes had our first sighting -- a pair of long-legged, white-rumped American avocets. “Look how they sweep their heads back and forth,” Edmondson said enthusiastically. Nearby were eight egrets and American wigeons with striped heads.

Gulls were everywhere, some standing like sentinels facing into the wind, but unlike Hitchcock’s gulls, they ignored us. “It’s a great art to identify gulls,” Burridge said. “A lot of people delay that part of their birding education indefinitely.” The problem: crossbreeding. There are Bonaparte’s gull, Heermann’s gull, the ring-billed gull....

We spotted a bufflehead, a sweet little black and white duck, and black cormorants, then a long-billed gray willet and black scoters. “Oh, there’s a female merganser,” Burridge said. “They dive, so every once in a while we’ll tell you to look at something and it won’t be there.”

There were juvenile gulls, still brown. Overhead, we spotted a hawk and two turkey vultures. The vultures were the ones with wings in V formation, while the hawk’s wings were extended out flat. Edmondson had just spotted a harbor seal peeking out of the water and now was training his telescope on a eucalyptus tree across the harbor, known to be a favorite of a great horned owl.

Each February Madrone holds a competition for spotting the most species within 24 hours. Everyone hopes to spot a rare bird, Burridge said, but “you have to write a convincing description that does not sound like it came out of a book.” Eyebrows are raised if someone repeatedly sees a bird no one else has seen or one that disappears each time another goes looking for it.

Edmondson became hooked on birding 12 years ago: “I retired and was getting kind of tired of gardening.” He saw a newspaper notice about bird walks; after taking two of them he was hooked. He likens the thrill of finding a colorful bird to his childhood joy in finding an Easter egg. “Some people just don’t get it. They think I’m crazy.”

We set up the telescopes to peer at some shorebirds: Black turnstones were actually turning over stones in search of small crustaceans, and white sanderlings pecked around in the wet sand. Nearby was a huge gathering of marbled godwits, the most prolific of local shorebirds save for the gulls.

At Bodega Head, a promontory jutting out between ocean and bay, the waves crashed below and the wind was formidable. Edmondson caught glaucous-winged gulls in his scope. Our hair was blowing in our faces. Burridge laughed and said, “We took up birding for the glamour.” Two sea lions frolicked by. It was all breathtaking.

We stopped at Campbell Cove, which has a tenuous connection to Hitchcock’s film. The Brennan house in the movie was a Bodega Head home owned by a feisty local named Rose Gaffney, a leader in a successful fight to halt construction of a nuclear reactor at the cove in the mid-’60s. The 90-by-120-foot hole now is a pond called Hole in the Head, a favorite stop for birders.

The birders’ enthusiasm was contagious. They talked of the challenge of identifying and classifying birds and understanding their places in nature. For Shurvinton, who, in her mid-40s, is among the younger birders, the moment that hooked her was spotting a snowy white owl in the Northwest.

It’s not those gulls and ravens that terrified moviegoers 40 years ago that worry today’s birders in Bodega Bay. True, ravens are worrisome, but that’s because they prey on young egrets. Birders worry more about pollution and disappearing habitats.

Still, if you insist on a Hitchcockian scare, the “Birds” video is on sale at the Tides shop, along with a mouse pad with Tippi’s likeness and this reminder: “Don’t forget to feed ‘The Birds.’ ”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.