China: A domestic wine industry starts to take root

Reporting from Shandong Province, China — — A few months before the 2008 Beijing Olympics, I read a blog post by an Atlantic Monthly correspondent about Chinese wine.

Chinese what?

I grew up outside New York City, where I ate hundreds of pounds of lo mein and pork-fried rice but didn’t see, taste or hear of Chinese wine. Even when I traveled to China in 2009 and 2010, I saw drinkers mostly tossing back beer and baijiu (Chinese liquor).

But Western-style wine is attracting the attention of China’srising middle class. Some Chinese buy red wine from Bordeaux, France, a purchase that wine experts say connotes high social status, and according to the Datamonitor Group, a London-based market analysis firm, China’s domestic wine industry generated more than $6 billion in revenue in 2008.

It’s hard to define the industry’s scope because no reliable data exists and some domestic winemakers use imported grapes, write Beijing-based wine experts Fongyee Walker and Edward Ragg, but it’s clear that China’s vineyards “cannot supply enough wine to meet the nation’s thirsty lips.”

In June, I booked a flight from New York to Beijing; I am not a wine expert by any stretch of the term, and I don’t speak Mandarin, but I thought it would be fun to visit Chinese vineyards and sample locally grown, Western-style varietals.

China Wine Tours, a California-based company, offers customized tours of Chinese vineyards and wineries for about $300 a day, but I decided to go the do-it-yourself route by emailing several Chinese winemakers with English-language websites — or at least websites with some English writing — to request private tastings.

The only soul who replied was Xin Zheng, winemaker at Chateau Huadong Parry, a Qingdao vineyard and winery named, in part, for its late founder, Englishman Michael Parry. The state-owned operation sits about halfway between Beijing and Shanghai on China’s east coast in what the China wine blog https://www.grapewallofchina.com calls the “Nava Valley” — a hotbed of up-and-coming vineyards.

Jackpot, I thought.

On a Saturday in New York, I booked a flight from Beijing to Qingdao and emailed Zheng to say my plane would arrive the following Wednesday morning. He replied cheerily to say he would meet me at the airport.

A Shandong chateau

The plane to Qingdao, a coastal city of 8 million, touched down in a fog. Zheng, 28, was waiting by the terminal with a driver and a company minivan.

Soon we were rolling past factories, construction cranes and drab, squarish apartments. As downtown Qingdao faded in our rearview mirror, a misty green hillside came into focus, and the minivan rolled into the driveway of a mansion that looked — improbably — like a French chateau.

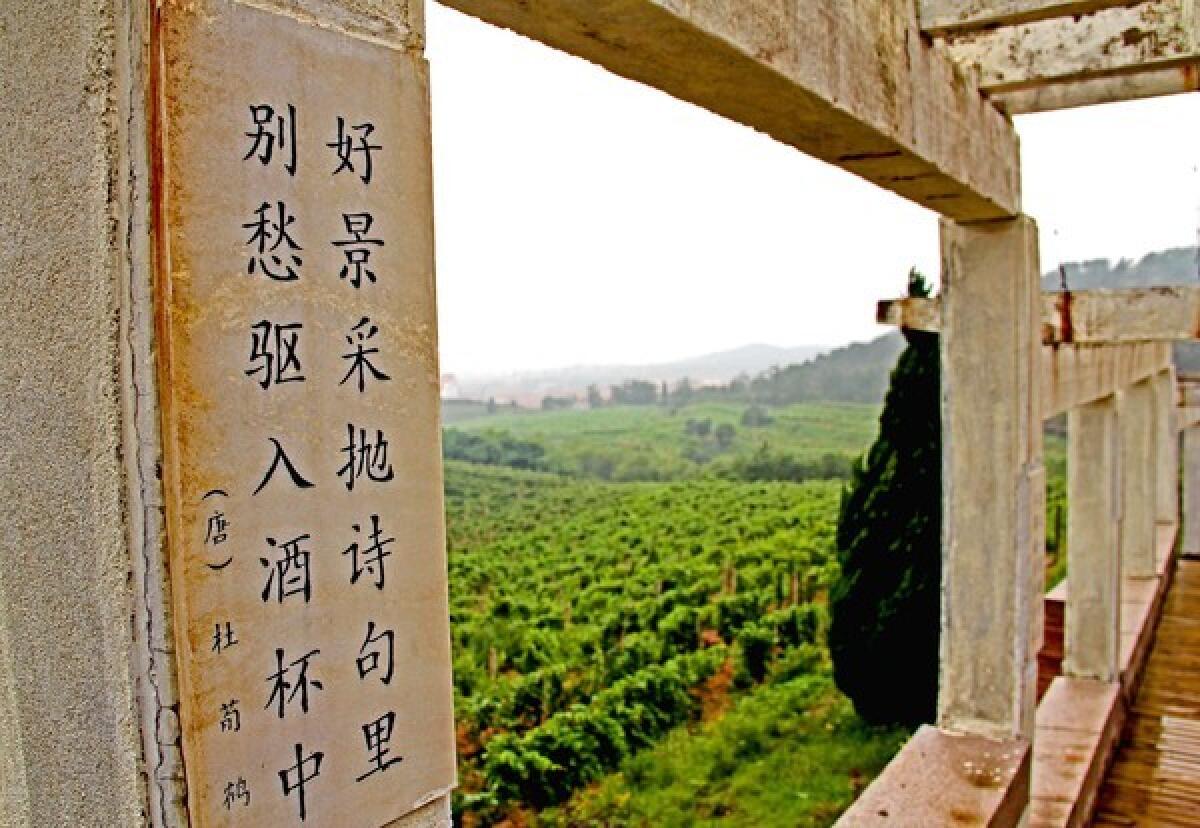

For the next hour, Zheng walked me around the nearby hills, which were studded with trellises of Chardonnay, Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon grapes. It might have been May in France, except for the punishing July humidity, and the fact that the hillsides were set against a backdrop of peri-urban sprawl and bisected by a boardwalk whose white stone pillars were engraved with Chinese poetry.

The Huadong winery — which is the same age as its winemaker — produces 7 million bottles each year and targets Chinese drinkers. “This is a very old society, but more and more Chinese people have been overseas, and our country is opening to foreigners,” Zheng said. “[Chinese] people are starting to change their lifestyles, and they’re starting to realize the benefit of drinking wine, if you drink it moderately and responsibly.”

Zheng added that he organizes wine-drinking demos at local universities. Most students can’t afford to buy fine wine on a regular basis, he said, but when they grow up and earn big salaries, “They’ll think of us.”

He led me to a cool, dark fermentation room, where the casks were labeled in French, and into the chateau, where in Victorian-style dining rooms I marveled at glittering chandeliers, sparkling wine glasses and spotless white tablecloths.

In an ornate drawing room, bottles of Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon were sitting on a coffee table near a candy red piano. In spite of my jeans and sandals, I felt like a country gentleman out of a Flaubert novel.

Zheng handed me a glass of the Cab.

“Smell the aromas,” he said. “It’s important.”

“Cherries?” I said.

“Dark fruit, earthy, like leather,” said Zheng, who studied viticulture in New Zealand. “It’s smooth, and that’s what our customers like.”

“It’s nice,” I said, swishing the Cab around my mouth. My layman’s impression was that this $12 bottle of Chinese wine was reasonably good.

The next Bordeaux?

In September, a Bordeaux-style wine from northwestern China’s He Lan Qing Xue winery won top honors at an international competition, the Decanter World Wine Awards. With Chinese businesses dominating industries once monopolized by Americans and Europeans, is Chinese wine on track to overtake the West’s?

Hardly, said Walker, founder and co-director of Beijing-based Dragon Phoenix Fine Wine Consulting and one of China’s foremost wine experts.

I met Walker and Ragg, her husband and business partner, on a torpid July afternoon at their downtown Beijing office. Brochures advertising Chinese vineyards were sprinkled across their conference table, but she said that the quality of most Chinese wines is “depressing.”

Walker said China’s nascent wine industry is constrained by both physical and bureaucratic climates: Wine-growing areas are either too cold or receive too much rain, and because the Chinese government owns agricultural land, winemakers don’t have much incentive to invest in infrastructure.

Fewer than 10 Chinese vineyards produce wine that Walker would consider “really good,” and only two stand out: Grace Vineyard, in central China’s Shanxi Province, and Silver Heights, in northwest China’s Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. Neither is sold outside the country, she said, but they are available at such fine dining landmarks as the Peninsula Shanghai and the Beijing restaurant Maison Boulud.

Fine wines don’t square with my shoestring budget, so in hopes of scoring a free tasting, I took a cab from Walker’s office to Pudao Wines, a store in the shadow of Rem Koolhaas’ CCTV building. But none were on tap at a pressurized tasting machine, and bottles of Silver Heights were retailing for nearly $65.

That evening I flew west from Beijing, vowing to sample more Chinese wine by other means.

Ganbei blues

A four-hour flight brought me to Urumqi, capital of northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, which Walker and Ragg say is more climatically “promising” for wine-grape growing than other parts of the country.

Despite emails and phone calls, I couldn’t arrange tours at any Xinjiang vineyard, so at a downtown Urumqi bodega I purchased three nondescript bottles of Xinjiang wine. The labels were mostly in Chinese, and the bill came to less than $10.

At the hostel where I was staying, I uncorked the bottles for a festive posse of Chinese and American tourists, and we drank over shouts of ganbei — bottoms up!” in Chinese — and platters of spicy chicken.

Xinjiang is famous for its grapes, but these inexpensive wines did not impress; the general consensus was that they were palatable only when chased by beer or baijiu.

“They taste like $4 or $5 American wines: cheap, with a bit of an alcoholic burn,” said Kalif Mathieu, 24, a Peace Corps volunteer from Illinois based in Gansu Province. “And this one? It’s wine, but not — know what I mean?”

I did: The wine in question had a nose of expired grape juice, and its Chinese label listed such ingredients as honey, lemons and roses. Chai Zi Li, a tourist from the eastern city of Nanjing, remarked that it tasted more like a wine cooler.

Chai, who owns the Nanjing bar Simple Chai, said the Chinese drinkers he knows typically buy wines from France, Chile, Australia and South Africa. But he added that some Chinese wine is “so-so.”

When I asked Chai if he serves Chinese wine at his bar, he smiled and lit a cigarette.

He said, “I use it for my sangria!”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.