Florida’s treasure islands

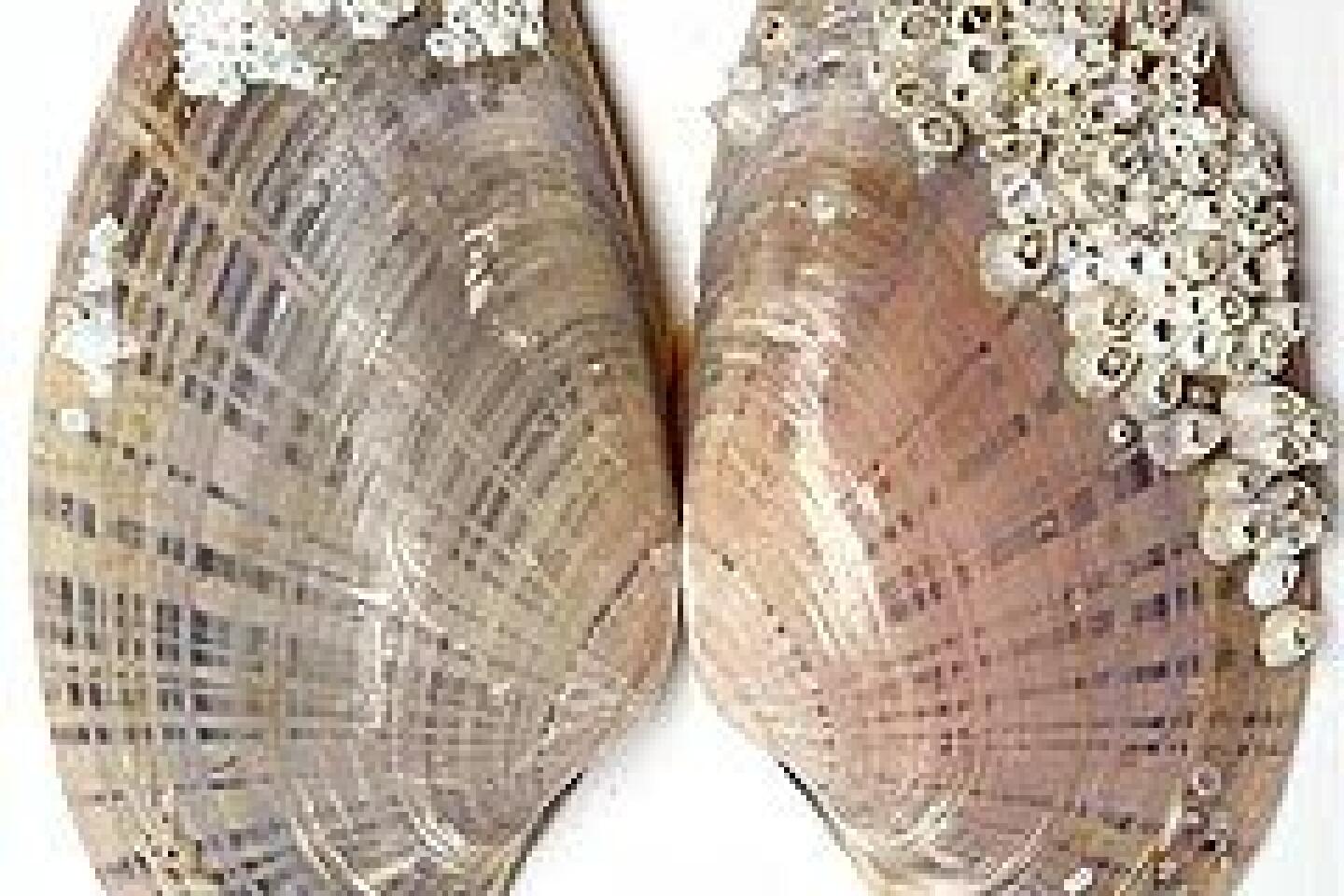

SANIBEL ISLAND, Fla. — Seen on the beach here: Florida fighting conchs, sand dollars, tapering lightning whelks, calico scallops, spiky murexes, kitten’s paws, all abundant and free for the taking, assuming the little critters these shells once housed have moved on.

Shells may be hard to find on other beaches, but they wash ashore in piles on Sanibel and Captiva, two slender barrier islands connected by a bridge off the west coast of Florida. The beaches of these islets, which rank third after the Great Barrier Reef and the Philippines among great shelling places of the world, catch treasures from the Gulf of Mexico like a colander cradles spaghetti.

That, in a clamshell, is why I went to Florida last month. It’s an odd destination, perhaps, for a Californian. Easterners, Midwesterners and even Europeans have long escaped winter here, basking in the sunshine when it’s cold and snowy back home. But I was surprised to find so much to like besides the weather and shells.

Sanibel is 12 miles long and up to three miles wide; to its northwest, Captiva is five miles long and never more than half a mile wide. Together they boast 16 miles of beach lapped by Gulf waters and bayside coasts fringed in mangrove trees, with their exposed roots and bushy foliage. Especially on Sanibel, the local government and residents have worked hard to curb development. High-rises and fast-food outlets with drive-through windows are banned.

Nature reigns here. Large tracts are given over to preserves, including the 6,400-acre J.N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge, home of alligators, manatees, dolphins and great flocks of tropical birds. The colors of the islands are baby pink and blue. The weather is generally balmy, so a tan is all but assured. Miles of paved bike paths make it fun and easy to get around. Sunrises and sunsets are visceral joys.

Basking in steamy heat

The islands, reached in about 30 minutes from Fort Myers by the three-mile Sanibel Causeway, are so narrow that each has only one major road. Traffic can be heavy, especially in peak season (January, February, March), so many visitors get around by boat or bike.

Steamy heat and the thick, rich smell of the sea settled over me as I drove across the causeway toward South Seas Resort on the north tip of Captiva. Feeling like a slowly melting ice cube, I checked in and got a map of the 330-acre luxury resort. It has more than a mile of Gulf-front beach, a golf course, marina, shopping plaza, swimming pools, tennis courts and restaurants, all so spread out that you have to take a motorized trolley to get around. Concrete block condos and a hotel cluster at the north and south ends of the resort; big white beach homes, available for rent, are strung out along the road between.

I stayed in a bayside condo with an abundance of amenities: a big-screen TV in the master bedroom, a coffee maker and microwave in the kitchen. The pale woods and wicker, bad seashore prints and colorful cushions worked hard to seem like decor, but they were a little too cheap and cheerful for my taste. That’s Florida, though. High style isn’t what you come for.

Sea life is. In the marina below my window, I saw my first manatee, or sea cow, an endangered species. It seemed at first just a huge, dark shadow in the water. Then its lovably ugly snout appeared as it slurped flotsam at the surface. It was one of many encounters with captivating sea creatures.

If finding shells is what you like, morning low tide, before the crowds arrive, is the time for a constitutional. The beach at South Seas is a beauty, with easy waves, soft sand and warm water. I found lots of clams and scallops near the resort’s north end, but nothing unusual. I picked up a heap, learning only later how to be more discriminating.

In the afternoon, I rode a rental bike 10 minutes south to the village of Captiva, which has several shops and restaurants, a pretty little seaside church and cemetery and just one general store. I lunched at the Bubble Room, a temple of Florida kitsch that’s whimsically decorated with flea market-like finds: big stuffed Santas, toy trains, movie stills. The waiters and waitresses wear Scout uniforms, and mine also had stuffed devil horns on his head. He delivered a heavenly sandwich of fried grouper swaddled in crisped-up pancake batter, and he tried to tempt patrons with such desserts as red velvet and double chocolate cake, in portions big enough to sink a dinghy.

Everywhere I ate on Sanibel and Captiva I found huge servings and such comfort foods as chipped beef, cheese steak and chicken wings. Invariably, TVs were tuned to football, and the bars were crowded and noisy.

There’s something stuck-in-the-’70s and goofy about this state. A man I met at the Mucky Duck, one of Captiva’s best sunset view bars, said that Florida, with its faulty ballots and alligators in the backyard, has supplanted California as America’s nutty fringe.

In such a place, the strange can seem commonplace, the commonplace strange and wonderful, as when it rained the next morning, sometimes so hard I wondered if I should start looking for a hurricane evacuation route. Instead I sat on my screened-in porch drinking coffee while palm trees whipped in the wind like go-go dancers. Afterward, a cold front moved in, bringing fresh air and daytime highs in the low 80s instead of the 90s. “This is just the kind of weather we wait for here,” said a woman at the reception desk of the Waterside Inn on Sanibel, where I stayed four nights after checking out of South Seas. “It’s hot enough for you guys and cool enough for us.”

Sandcastles and shell seekers

The Waterside is a small, carefully kept mom-and-pop place with a two-story motel wing, a little pool, shuffleboard courts and wood cottages painted sherbet colors. My motel room had two double beds, a TV, kitchenette and balcony, decorated in a modest, chain motel kind of way. Best of all, the classic Florida inn sits right on the beach, where toddlers in sunbonnets build sandcastles and oldsters with kitchen spatulas and plastic milk jugs hunt for shells.

The beach was freshly glazed with treasures the morning after the storm, and it seemed as if all the Gulf’s fighting conchs had washed up on my doorstep. I couldn’t stop picking up shells. I was totally absorbed, my body bent in the characteristic “Sanibel stoop.”

While I was searching, I met a man looking for his wife. “She’s been gone for hours,” he said. “She left without drinking coffee or taking her meds.”

Like gambling, shell collecting is addictive.

Seeking less frequented hunting grounds, I went on a three-hour shelling cruise with Capt. Jim Burnsed, whose boat is docked at ‘Tween Waters Inn on Captiva. Just being out in a boat, zipping through Redfish Pass, was glorious enough. But when we moored off the beach at Cayo Costa Island, north of Captiva and Sanibel and accessible only by boat, I started finding sand dollars and shiny shells called olives.

Later I visited the Bailey-Mathews Shell Museum on Sanibel, where a video credits the low water level for the conchological bonanzas. In the Great Hall of Shells I saw a display on right- and left- handed shells (a differentiation based on which way they spiral), 19th century sailors’ valentines with shell-inlaid hearts and flowers made by Caribbean women for seafarers to take home to their wives, and a rare brown-checked junonia shell that was 6 inches long.

When shelling and soaking up the Florida sunshine paled, I sampled the many other distractions of Sanibel and Captiva, such as biking through the Ding Darling refuge, established in 1945. Darling, a conservationist and Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist who died in 1962, was instrumental in keeping the state from selling prime wildlife habitats to developers.

The refuge’s four-mile wildlife drive reminded me of sequences in “The African Queen.” To the left, an alligator lay, log-like, in the mangrove, and to the right, flocks of white egrets and ibises fed on a sandbar.

I also joined a guided tour for a sunset kayak trip to rookery islands in Tarpon Bay, which is part of the refuge. As the sun melted in a pink puddle, bottlenose dolphins circled the boats and hundreds of birds flew in to roost on small, mangrove-covered islets. Darkness fell as we paddled to shore, guided by moonlight.

Between adventures, I shopped in the Sanibel business district along Periwinkle Way. I bought chocolates in the shape of shells and a bottle of bleach to rid my cache of its fishy smell. I couldn’t tear myself from She Sells Sea Shells, a shop devoted to shells, where junonias went for $30 each and an extremely rare, imported Bay of Bengal cone shell was priced at $250.

Sanibel is all about shells. You can’t get away from it. Surely you don’t have to ask what I brought home as a souvenir.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.