Pinball never died in this arcade

- Share via

LAS VEGAS — Tim Quintana hunches over a pinball machine and stares down Spider-Man’s archenemies: Kingpin, Lizard and Scorpion. He pulls the plunger and a silver ball shoots onto the playfield, a maze of brightly lit bumpers and targets.

The ball darts over a comic-book-style drawing of Spider-Man reaching for his lady love, Mary Jane. The machine beeps: Blip-blip-blip-blip. The ball clangs off two mushroom-shaped bumpers. It plows into three square targets. Blip-blip-blip-blip.

With each blip, Quintana’s score rises: 448,400. 448,500. The ball bumps a target decorated with a small spider web. A green dot lights up. More blips. More points. More blips.

Silence. The ball is stuck.

It shakes Quintana out of his pinball trance. A welfare caseworker, he whizzes through his lunch breaks in this dim strip mall storefront called the Pinball Hall of Fame.

“It makes you feel like a kid for an hour,” he says. “Forget work, forget everything for one hour.”

Quintana seeks out the games of his youth -- like The Amazing Spider-Man -- among the 200 machines belonging to a pinhead named Tim Arnold. People come to his arcade to relive childhood afternoons. His Hall of Fame has also become a memorial for a pastime upstaged by Xboxes, PlayStations and Wiis.

Pinball, once a pop-culture touchstone, is sputtering. Only one manufacturer remains -- Stern Pinball Inc. in Illinois. In the early ‘90s, the company made up to 40,000 machines annually. Today, it turns out just 10,000, and about 40% of them are sold directly for home use.

Roger Sharpe, co-director of the International Pinball Flipper Assn., blames the decline on the machines themselves. The newer ones have a half-mile of wiring and about 3,500 parts. It’s inevitable something will break.

Arnold’s arcade is a throwback, with Mike and Ike candy machines, mismatched carpet, change machines rescued from Dumpsters, and posters for mid-’90s games such as Congo, whose slogan is: “Hippos, Snakes and Killer Apes. (And that’s just the first ball).” The Hall of Fame is open daily for at least 12 hours, and Arnold is there much of the time. There’s no phone: He fears pinball fanatics would take up his days with stories.

The customers, about 300 daily, are mostly male and middle-aged. Some are recovering gambling addicts who find the lights and pings a substitute for slot machines. They gawk at a slick Wheel of Fortune and an eerie Pinball Circus, which has a clown with an exposed brain and a figurine twisted like a Cirque du Soleil performer. Only two circus games were made.

“This is history, though it may be more whimsical,” says Sharpe, whose group runs pinball tournaments and oversees player rankings. “But it’s got its place in our culture and shouldn’t be forgotten.”

Sharpe says Arnold, who spends afternoons poring over coffee-stained blueprints to fix his machines, is helping “to keep this game alive.”

When Arnold was growing up in Michigan, pinball was immensely popular. But, he recalls, his parents cringed at how much he liked playing the games. Many government officials equated pinball with gambling. It was banned in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago until the ‘70s, when Arnold was a teenager.

This, of course, made the game even more appealing.

Arnold had an entrepreneurial streak and at 16, he was buying gumball machines and installing them in stores. He, his brother and a friend emptied their wallets to buy their first pinball machine, Mayfair, for $165. The game is based on the movie “My Fair Lady,” and its bygone-era artwork depicts ladies in feathers and gentlemen in top hats.

Arnold eventually owned so many pinball games that his parents bought him a Dodge van so he could transport and install them in pizza parlors and arcades.

He was so dreading college in the mid-’70s that he and his older brother indulged in what seemed a boyish fantasy: They opened an arcade. His parents weren’t thrilled, but they appreciated their sons’ money-making bent -- Dad was a salesman who peddled miniature replicas of the Statue of Liberty.

The arcade was a disaster. People swiped money from the games. The building’s electrical wiring caught fire. In about three months, the arcade closed.

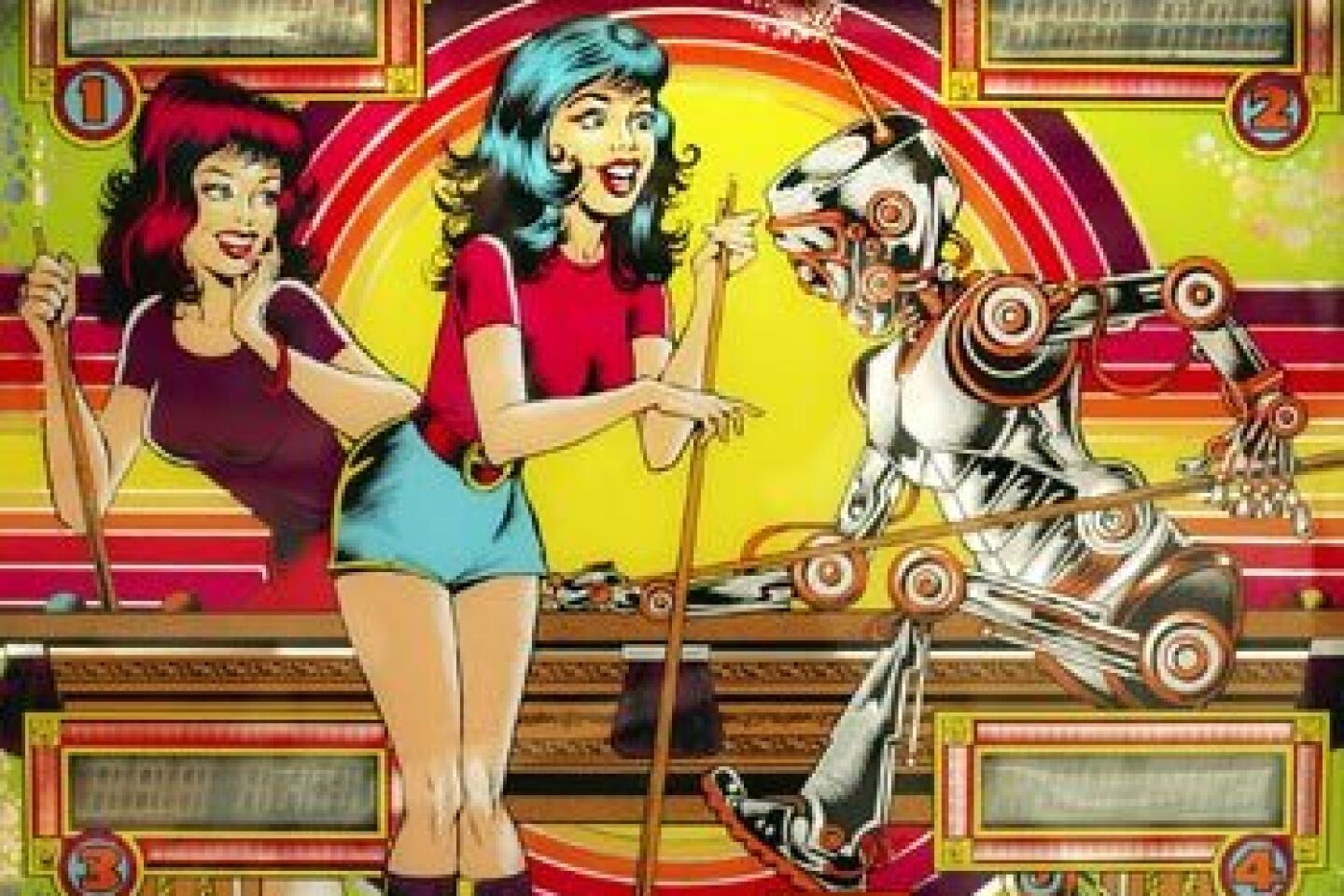

A few months later, in 1976, the brothers heard about a shuttered arcade in East Lansing. They rented the space, installed 28 machines and named it Pinball Pete’s. Near Michigan State University and a bar teeming with college kids, this arcade was far more successful. Pinball was also booming. The Who’s campy rock opera “Tommy” spawned the hit song “Pinball Wizard” and a machine with back glass depicting the movie’s stars. The brothers opened another Pinball Pete’s. And another. They ran seven, all in Michigan.

Arnold eventually grew tired of juggling the businesses, and he loathed the onslaught of graphics-heavy games: He thinks they dumbed down arcade play. He retired in 1990 at age 35 with about $1 million. Arnold and his partner, Charlotte Owens, lived comfortably off his investments.

Arnold had long aspired to open a pinball repository. His rationale was similar to that of a kid with the newest video console: What’s the use of having cool games if you’re playing them alone?

His pinball palace, Arnold figured, would only work in a tourist-packed city. New York and Los Angeles: too expensive. Orlando: too humid. In 1990, he and Owens bought a house with a tennis court on 2 1/2 acres in Vegas, whose neon Strip resembles a pinball game’s playfield.

He lined his tennis court with games and covered them with tarps. He built a 10,000-square-foot windowless hangar in his backyard. To get there, you walk by other evidence of Arnold’s affinity for cast-offs: 2,000 sun-cracked bowling balls; a turnstile from the New York New York casino, and a 10- to 12-foot-long fiberglass hand that Arnold rescued from Caesars Palace.

He has packed the hangar with 800 or so of the bulky machines, some stacked 18 feet high, while they wait to be fixed. Many were rescued from drained swimming pools, swap meets, car dealerships and tobacco warehouses.

For years, Arnold lugged the machines into the backyard for parties to raise money for his repository. In 2006, 16 years after moving to Vegas, Arnold opened the nonprofit Hall of Fame in a dowdy plaza a few miles east of the Strip. A devoted volunteer known as Hippy helps care for the 4,500-square-foot space. Arnold wishes he could move to a bigger place with room for 600 to 800 games (including one each of all 384 produced by his favorite manufacturer, D. Gottlieb & Co.).

Arnold doesn’t charge admission. Each month, he takes in about $16,000 from the games played, but some months that’s barely enough to get by. Proceeds go to charities (mainly the Salvation Army), which led Las Vegas CityLife, an alternative weekly, to name Arnold one of its “local heroes.”

On this afternoon, Mark Scheffki walks into the Hall of Fame, and nostalgia takes over.

Scheffki, 46, drove here to determine the worth of his parents’ 1970s machine, Bali-Hi. But he was drawn instead to the decade-old game Scared Stiff. Elvira -- the self-proclaimed “Mistress of the Dark” -- skulks on its back glass with a black cat, a skull, a frog and a hand waving a machete. Scheffki sprints through levels that are “Hair Raising!” and “Skin Crawling!” Elvira’s voice shouts: “Frogs everywhere!”

The ball shoots past a coffin and two Elviras with low-cut dresses and come-hither stares. The machine mimics a bubbling caldron: pop-pop-pop-pop. The ball wriggles through a ramp, skirts flippers designed to resemble bones, and disappears.

Scheffki, a plumber weaned on pinball as a kid in Chicago, fishes into his camouflage shorts for quarters. He racks up 3,042,230 points. The machine jams.

Elvira: “You just don’t listen, do you?”

Arnold, 52, hears this from across the room, “like how mothers can sense when their kids are in trouble.”

He hustles over, unlocks the machine and plucks out a stray part. Scheffki asks Arnold about the Bali-Hi machine, and Arnold says it could fetch up to $1,000 online.

“Lucky it’s not an eight-track tape player,” Arnold says wryly. “Then it would have no value.”

Fans are whirring overhead. A machine somewhere is humming the theme to “The Lone Ranger.” In the row behind Scheffki, Quintana gives up on Spider-Man. He heads to a machine immortalizing the band Kiss.

“I’m the biggest freaking Kiss fan,” Quintana says in a near-whisper. He strokes the glass. A notecard says this was the 11,381st of 17,000 Kiss machines made -- “a true classic.” Gene Simmons’ tongue unfurls in one corner; Ace Frehley glares from the other. Kiss babes preen in black bodices. Snakes spit fire. Quintana’s game is over in less time than a song. “There’s nothing worse than putting three balls right down the middle,” he says.

Quintana, 30, who has a short ponytail and a soul patch, got hooked on pinball a year ago when a friend stumbled onto the Hall of Fame. Quintana steps outside to smoke. His phone rings. It’s his wife.

“I’m playing pinball,” he says.

She understands, and tells him to call her later.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.