Mexico City: A sea of Juarez streets

- Share via

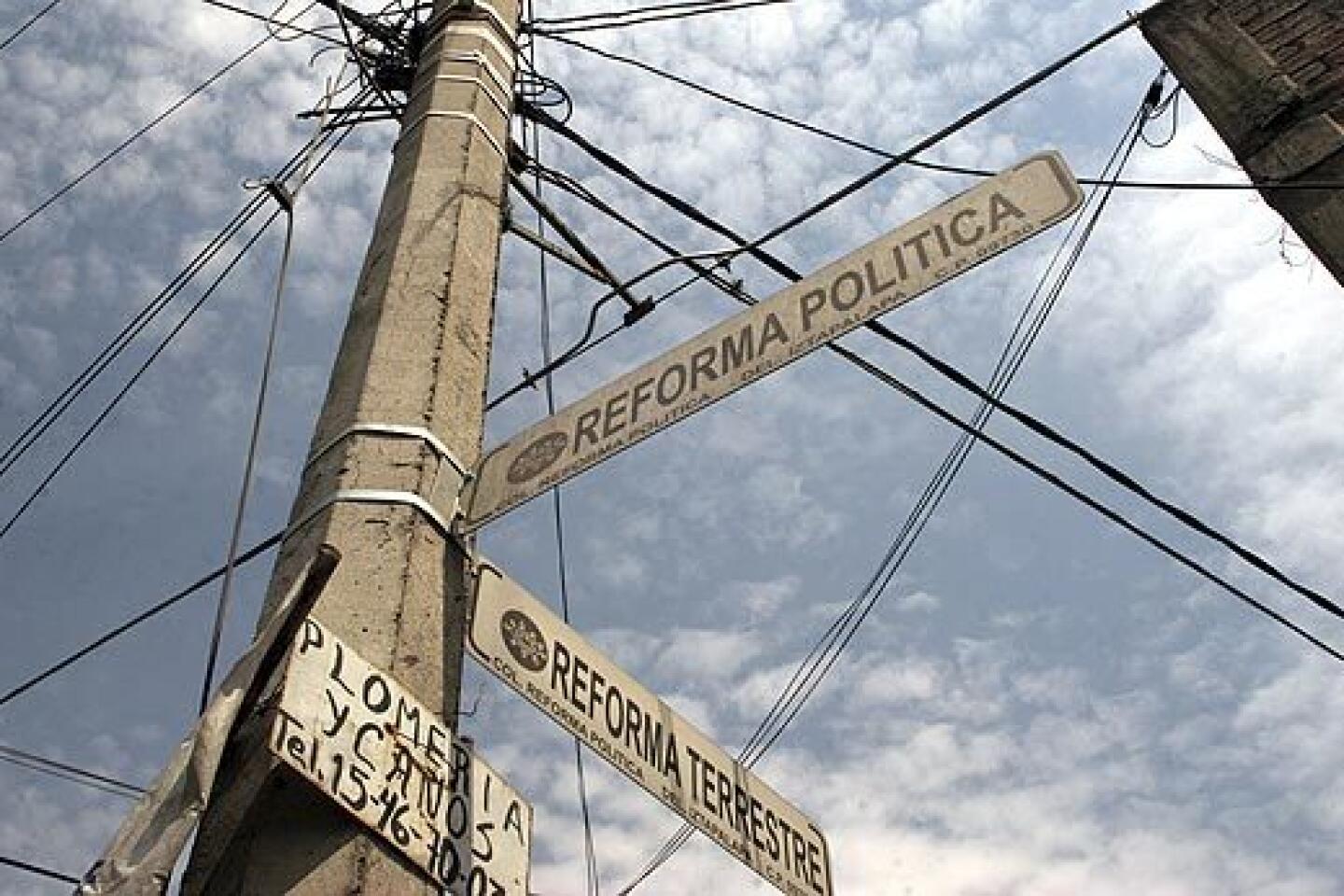

MEXICO CITY — No matter where you drive in this megalopolis, it’s hard to miss Juarez Street. That’s because there are 632 of them. Hidalgo Street is almost as ubiquitous, with 624 incarnations. At least 500 streets are named Zapata.

But you can also find Sea of Tranquillity and Good Luck or, if those fail, Tequila. There’s a street called Disneyland and lots of Progress all over Mexico City’s sprawling traffic grid, if only lurching movement.

Among the few traffic-related charms of the car-choked capital city are the names of its 32,000 streets -- 73,000 if you count the surrounding metropolitan area. Peruse the most popular street atlas here and you’ll encounter history and whimsy, the fanciful, the soaring and the clunky (Metallurgical Resources lands like lead, even in Spanish).

Many street names follow a theme, lending symbolic cohesion to neighborhoods. Streets in the wealthy Polanco section, for example, carry the names of famed men of thought and letters: Virgil, Galileo, Cervantes -- even Dickens has a street in this most un-Dickensian redoubt of privilege.

A parched swath not far from the airport, itself named after Benito Juarez, is awash in great seas, at least on paper. Here, you can lounge next to the Pacific Ocean, Red Sea and Gulf of Finland on the same day. Other neighborhoods are sprinkled with virgins, lakes, volcanoes, flowers.

Baghdad has a street.

In an ever-spreading city, where as many as 1,200 streets are christened each year, it is not easy to avoid repetition, even with the help of botany books. That can complicate the job of navigating the place.

Want to flummox a taxi driver? Ask for Emiliano Zapata street, named after the peasant leader from Mexico’s revolution, but omit the neighborhood. Punch the street named Michoacan into a dashboard GPS system and what comes up is a long and dizzying list of possibilities, sorted by postal codes.

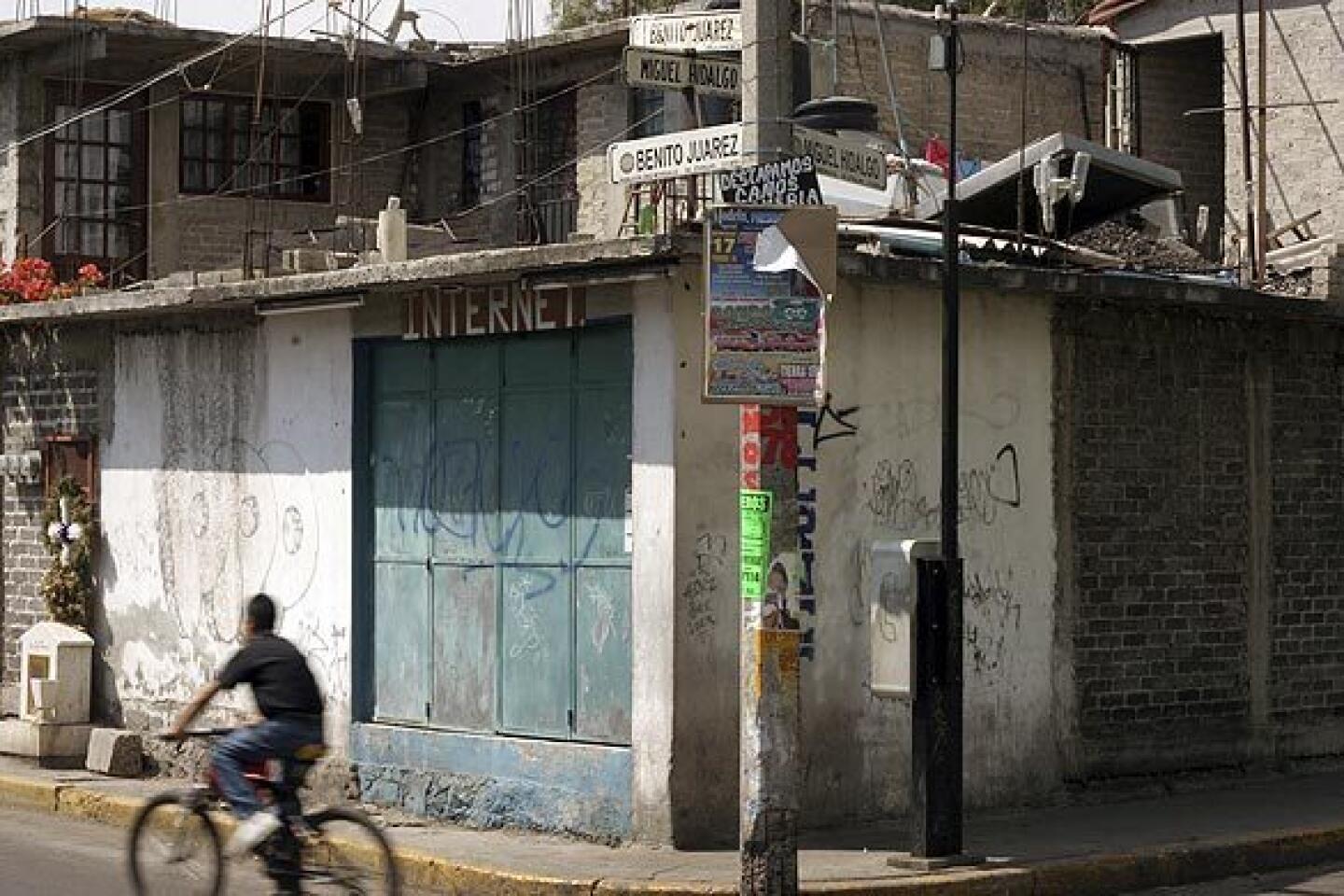

“Once I asked a taxi driver to take me to Cerrada Hidalgo and he took me to the Hidalgo metro station,” said Alix Colin Becerril, who lives on a tiny, dead-end street named Hidalgo in the Hidalgo neighborhood, just a few blocks from the edge of a municipal borough called, you guessed it, Miguel Hidalgo.

But Colin, 23, who works in an ice cream shop, said she’s pleased to have her street named after an icon of Mexican history. Hidalgo is known for letting loose the cry for independence that launched the uprising against Spain in 1810 before his capture and death a year later.

“That your street has the name of a leader who represents some of our heritage -- that’s good,” she said.

Not everyone is pleased to have a name from history attached to their street.

Last year, the Mexico City assembly ordered municipal officials to strip the name of former President Luis Echeverria from city streets because of what leftist members said was his role in the infamous 1968 police crackdown against student protesters when Echeverria was interior minister, and in the government’s “dirty war” against left-wing activists while president in the 1970s.

So far, though, authorities haven’t begun to erase Echeverria’s name from the 16 streets that carry it because they are waiting for officials in the affected boroughs to weigh in with alternatives.

“If they removed the name of everyone who had a problem in his past, the capital wouldn’t have the name of any official,” groused Javier Sanchez, who runs a pet shop with his wife on Luis Echeverria Street in the Presidentes neighborhood. “We have a lot of problems much more serious than the name of a street.”

Guidelines for naming Mexico City’s streets, adopted along with the formal creation of an official Nomenclature Commission in 1998, permit the use of proper names.

Many evoke Mexico’s dearly held past, such as Juarez, the 19th century president often compared to Abraham Lincoln, or Hidalgo, the priest and rebel leader credited with igniting the crusade for Mexican independence earlier that century. It’s a male-heavy roster, though a striking exception is Sister Juana Ines de la Cruz, a 17th century nun and poet.

Municipal officials have taken note that famous lakes or mountain ranges can be a safer bet than people.

“Proper names that have to do with geography have less political baggage,” said Jesus Velazquez Angulo, who directs a 27-member staff that dreams up street names and installs the signs. “It allows us to reach consensus that gives social recognition to the names.”

It’s not always so smooth, however.

Last year, Velazquez recalled, district officials worked up a naming scheme for a neighborhood that had just been granted official recognition. The streets were to be named for lakes. But when city workers showed up with the signs, residents rebelled, demanding to keep the names they had been using.

In the end, Mexico City officials relented. The signs were taken down. Replacement signs, white with black letters, went up: the newest street names in Mexico City.

Among them, perhaps inevitably, are Juarez and Hidalgo.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.