Latinx Files: How a famous pianist picked a fight with reggaeton

- Share via

Hey folks, this is Fidel. Every once in a while, the Latinx Files will feature guest writers. This week is one of those weeks. I’ve asked Katelina “Gata” Eccleston to write the main story. She is a music historian, creative and entrepreneur whose work focuses on the analysis and social paradigms of reggaeton. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram, and while you’re at it, read this Harper’s Bazaar profile of her. Take it away, Katelina!

Back in November concert pianist James Rhodes, in talking about the lasting legacy of classical music at a conference, said the following in Spanish:

“Explain to me, please, Reggaeton and Bad Bunny. I can assure you, I am assuring you I’m not saying it’s sh—, but literally I don’t understand the popularity of this type of music. If there’s anyone who can explain to me this is why it is the best, why I’ll listen to you with all of my soul.”

His remarks sent reggaeton fanatics worldwide into a frenzy.

OK, Mr. Piano Man. I’ll bite. Let’s take a moment to actually compare classical music and reggaeton.

Let’s start with the obvious. Classical music has long been associated with and elevated by the ruling classes. It is celebrated in the Boston Symphony Hall and in New York City’s Lincoln Center. It’s used in movies to imply sophistication.

Perreo, the soul of reggaeton, was created in the street. It is often minimized to music that degrades and sexualizes women, dismissed as repetitive, misogynistic noise despite its nuance and legacy of resistance against white supremacy.

By Rhodes’ own admission, classical music has an image problem. It has a “bad reputation for being boring, classist or elitist.” He does his argument no favors by dismissing reggaeton, a genre that serves as a testament and celebration of the survival of Black people.

Ironically I believe both genres are more similar than Rhodes would like to let on. At their core, they share one key trait: drama. A successful live classical music performance is dependent on a crescendo to elicit a range of emotions from the listener. Reggaeton has that too. The call and response.

Reggaeton wasn’t created on a whim or in a vacuum.

Its DNA is the same as other genres created by Black people, from Negro spirituals in plantation fields to gospel in churches. You see the threads continue through blues, funk and R&B in the lounges to hip hop in the Boogie Down Bronx.

And then from reggae unifying opposing political parties in Jamaica to dancehall and reggaeton, first in Brooklyn then Panama, and finally in Puerto Rico.

Simply put, perreo’s intentional composition is the continuation of a legacy that aims to maintain and inspire a disenfranchised people.

Call me biased, but in my mind, this music is as robust and as sophisticated as any other genre out there.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Reggaeton’s creation process is often stigmatized due to ignorance regarding its musical makeup. Sure, each song within the genre has a constant base, known as the Dembow beat and or the pounder riddim, but what makes each song very different are the interpolations, and incorporations of other inherently African genres like salsa and the movements inspired by the nuance.

If there is an artist who understands the complexity and flexibility of reggaeton, it’s Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio. You see, when his distinct rap-style is blended with the nostalgic synthesized melodies, complemented by tempos further emphasizing the drama of his message — El Conejo Malo takes his audience on an experience that transcends social paradigms like gender and age.

Bad Bunny, a versatile artist whose work draws from metal, Dominican dembow, trap, reggaeton and perreo among others, has brought this sound to unparalleled heights. You don’t have to take my word for it. You can just ask any of his billions of listeners.

His music may be foreign to those who frequent Bach, Beethoven and others alike, but what those people fail to understand is that El Conejo Malo and the hundreds of artists who preceded him — especially Black artists — created secular music for the purpose of rising, and that profound sense of pride is all of the dignity and justification to exist on its own.

Rhodes, your projections are miscalculated because you ignore one key fact. Black people created music like perreo to speak to their injustices, to inspire faith among them, and to spread the message that like everything else, they will survive and will do so with joy.

Just as salsa music continues to shake the world with its tumbao and just like rock rattled the cages of those who deemed it too wild, reggaeton will continue to liberate millions of minds and caderas with its perreo. For that reason, reggaeton is here to stay.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Pero sigue siendo el Rey.

Hey guys, it’s Fidel again.

Vicente Fernández, el Ídolo de México, died on Sunday at 81. Lest I be accused of being a hypocrite (it was admittedly not my best take), I’ll refrain from sharing a personal story about the legendary singer.

It’s undeniable that his death was a great loss for the Mexican and Mexican American community. In Los Angeles, fans turned his star at the Hollywood Walk of Fame into a makeshift memorial (with merch and all).

For many, like KQED reporter Blanca Torres, the death of El Rey made a lot of people think about their relationships with their dads.

Fernandez was by no means perfect. The singer’s death resurfaced criticisms over his past sexist and homophobic comments. But as my colleague Gustavo Arellano notes in his appreciation column, “those defects are also a reminder that the totality of someone’s life should supersede their mistakes.”

His music is part of the personal soundtrack of millions of people, accompanying Mexicans and Mexican Americans of all ages in their moments of sorrow, but also in their moments of joy and triumph.

If you’re not familiar with his music, Gustavo also put together this playlist of Chente’s essential songs. You can find The Times’ full coverage of his death here.

Things we read this week that we think you should read

— On Wednesday the UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Initiative published a report that found that just 4% of op-eds published by the Los Angeles Times between January 2020 and May 2021 were written by Latinx authors. They also found that 95% of Times op-eds published during that period “made no explicit mention of Latinos or Latino communities.” Yikes.

In response, The Times pointed to recent hires and highlighted some op-eds that centered the Latinx community, while also reaffirming its “commitment to improving diversity, equity and inclusion at the Los Angeles Times.”

It’s true that my employer has taken some steps in closing the representation gap, but it’s also true that the work is by no means over.

— Steven Spielberg’s remake of “West Side Story” hit theaters this weekend and was met by largely positive reviews (here is The Times’) but underwhelming box office returns. Because we’re all about centering Latinx voices in this newsletter, I put out a call on Twitter looking for reviews written by Latinx writers. Here are the reviews from Nerds of Color, Pop Sugar Latina, Latino Rebels, But Why Tho? Podcast, Full Circle Cinema, and Todas PR (written in Spanish). Julio Varela also wrote this op-ed for the Washington Post. I also recommend this video essay featuring Kristen Maldonado and Josie Marie Meléndez, two Puerto Rican film critics.

— From “the tech won’t save us” department: The Intercept is reporting that Brinc, a well-funded startup in the business of selling robots and drones to police, tried to market a border enforcement drone capable of tasing undocumented immigrants back in 2018. The revelation completely undermines the company’s own stated values and ethics, which promise that they’re the good guys “who won’t build a dystopia.” I don’t know, guys, this feels pretty dystopian to me.

— I’m admittedly bad with my money, but you know who isn’t? Utility desk editor Jessica Roy, who is the undisputed queen of never leaving money on the table. If you’re looking to take control over your personal finances in the new year, you’re in luck! The Times is launching “Totally Worth It,” an eight-week newsletter written by Jessica. You can sign up here.

And now for something a little different...

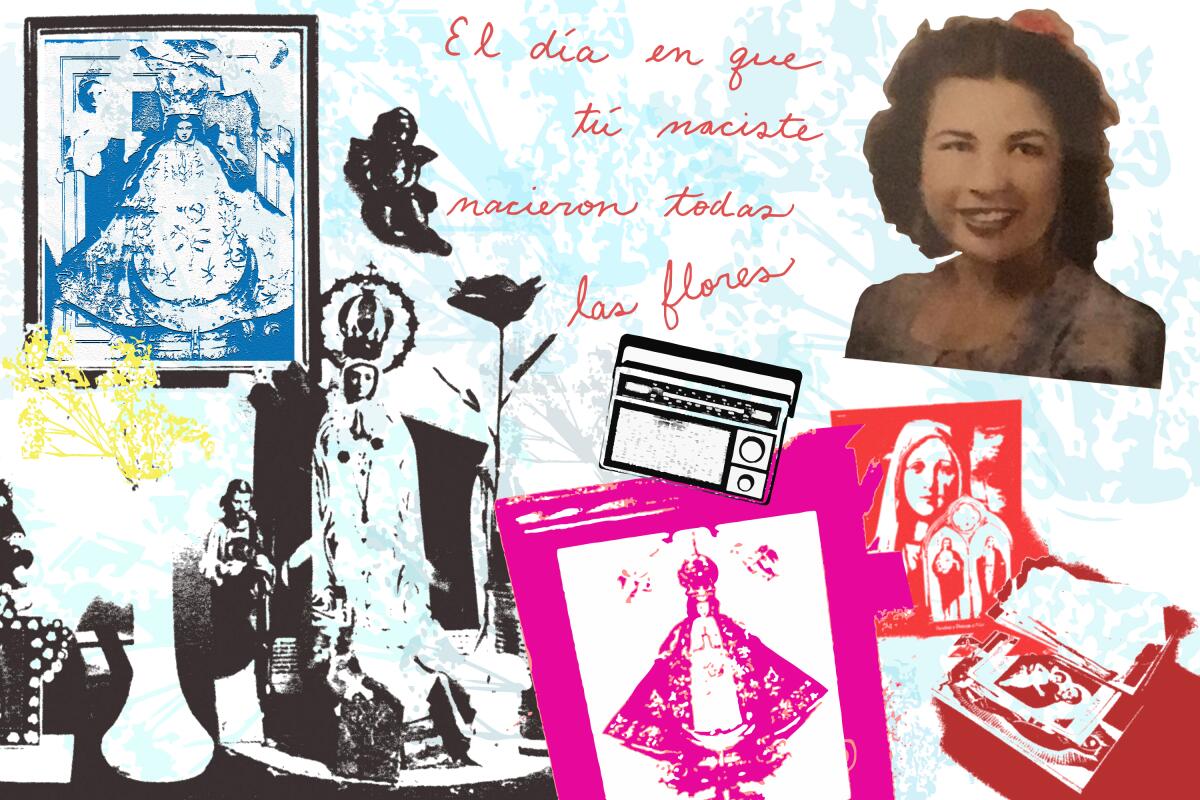

Marisol Limón Martínez is a visual artist, musician, and writer. Her work is based on narratives from memories and her dreams. She is currently working on her first novel about a family who operate and live in a Spanish-language cinema in San Antonio, Texas.

“This composition is in honor of Nana, my grandmother, Margarita Martinez, whose birthday is near Christmas. The images are based on photographs I took in her home after she passed away in the fall of 2016. Nana’s personal devotion to La Virgencita taught me the meaning of faith. I have especially strong memories of her during this season and the loving prayers and blessings she always gave our family and community.”

Are you a Latinx artist? We want your help telling our stories. Send us your pitches for illustrations, comics, GIFs and more! Email our art director at martina.ibanezbaldor@latimes.com.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.