El Paso Walmart manager, who helped customers survive and employees cope, finds solace in baseball

- Share via

EL PASO — Robert Evans stood on the grass of the baseball field Wednesday night, and a little bit of him was a kid again.

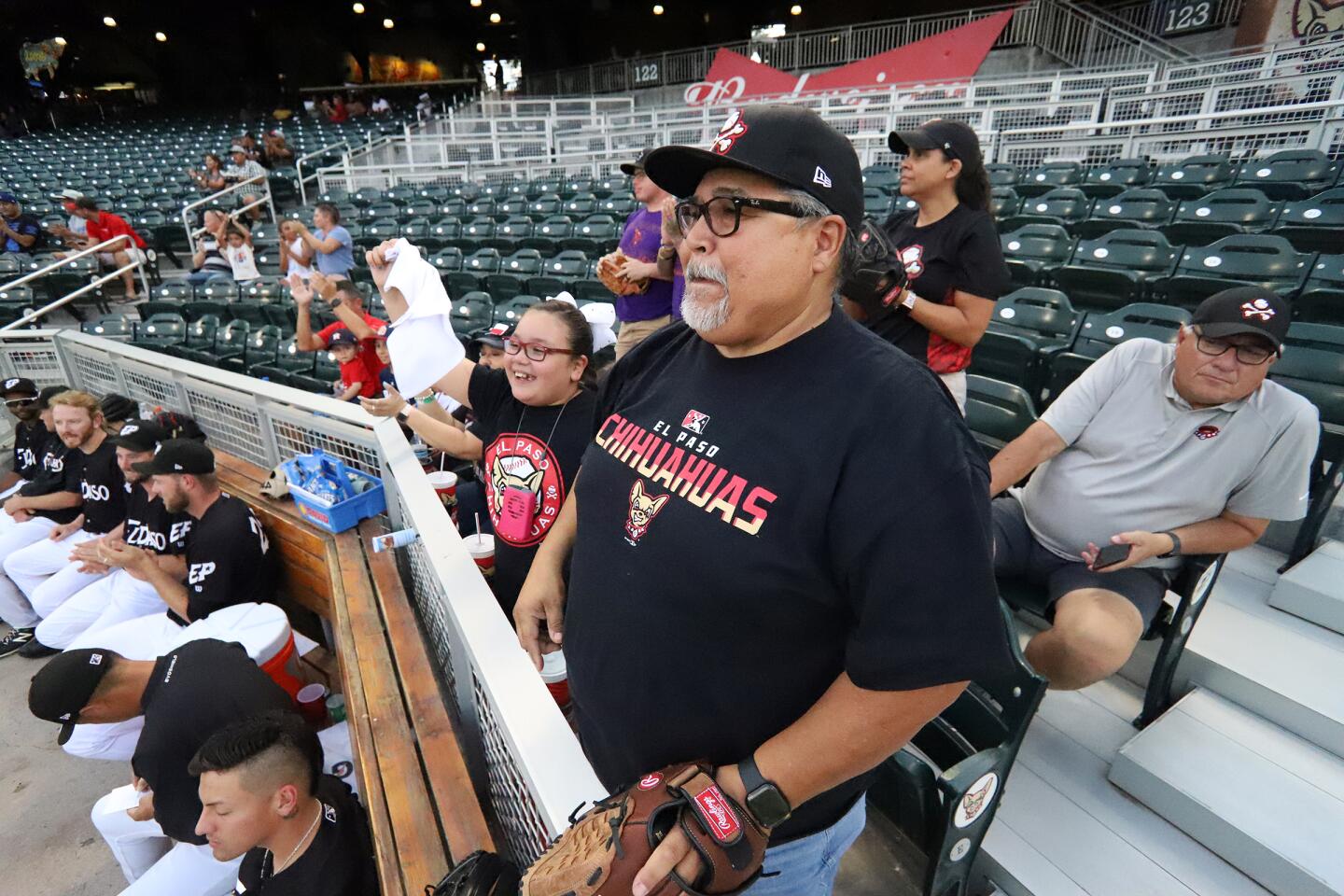

He had played second base and some shortstop growing up in El Paso. When he was young, in the 1970s, he’d go to minor league games with his grandfather. “He could answer any trivia question they put up there,” Evans said. “He loved baseball.”

Evans remembered — he couldn’t have been more than 10 — sitting near metal and wood bleachers, waiting to catch baseballs that flew off the bats. Sometimes he’d keep them. Sometimes he and his friends would trade them in for snow cones.

Baseball was a place to dream. A place for joy. A place where things made sense: 90 feet between the bases, three outs per half-inning, and a diamond shape of grass and dirt hemmed in by foul lines and a home run wall.

But what happened in El Paso on Saturday morning made no sense. It was madness. The 44-year-old Walmart manager had been in the parking lot of his store when a gunman approached. He saw the first bullets fly and the first customers crumple. Evans ran into the store, yelling, “Active shooter!”

When his daughter was shot, he prayed and raced to save her.

He and other Walmart employees began directing people to the back exits as the gunshots popped. “I told them to head for the TVs along the back wall,” Evans said.

There was blood. Screaming. A lot of death. He spent the rest of the day at the store, which had become a massive crime scene. Evans would be the last store employee to leave the scene Saturday night after being interviewed by investigators.

The days after were a blur, but he didn’t have the luxury of shutting down. Store employees had left medications, work visas and personal belongings in lockers and couldn’t pick them up until Walmart had set up a site at a nearby hotel. Evans stood in the hotel lobby Monday as they arrived, hugged them and helped them find counselors and reclaim their items. He did it again Tuesday. And then on Wednesday. Sleep hadn’t been easy.

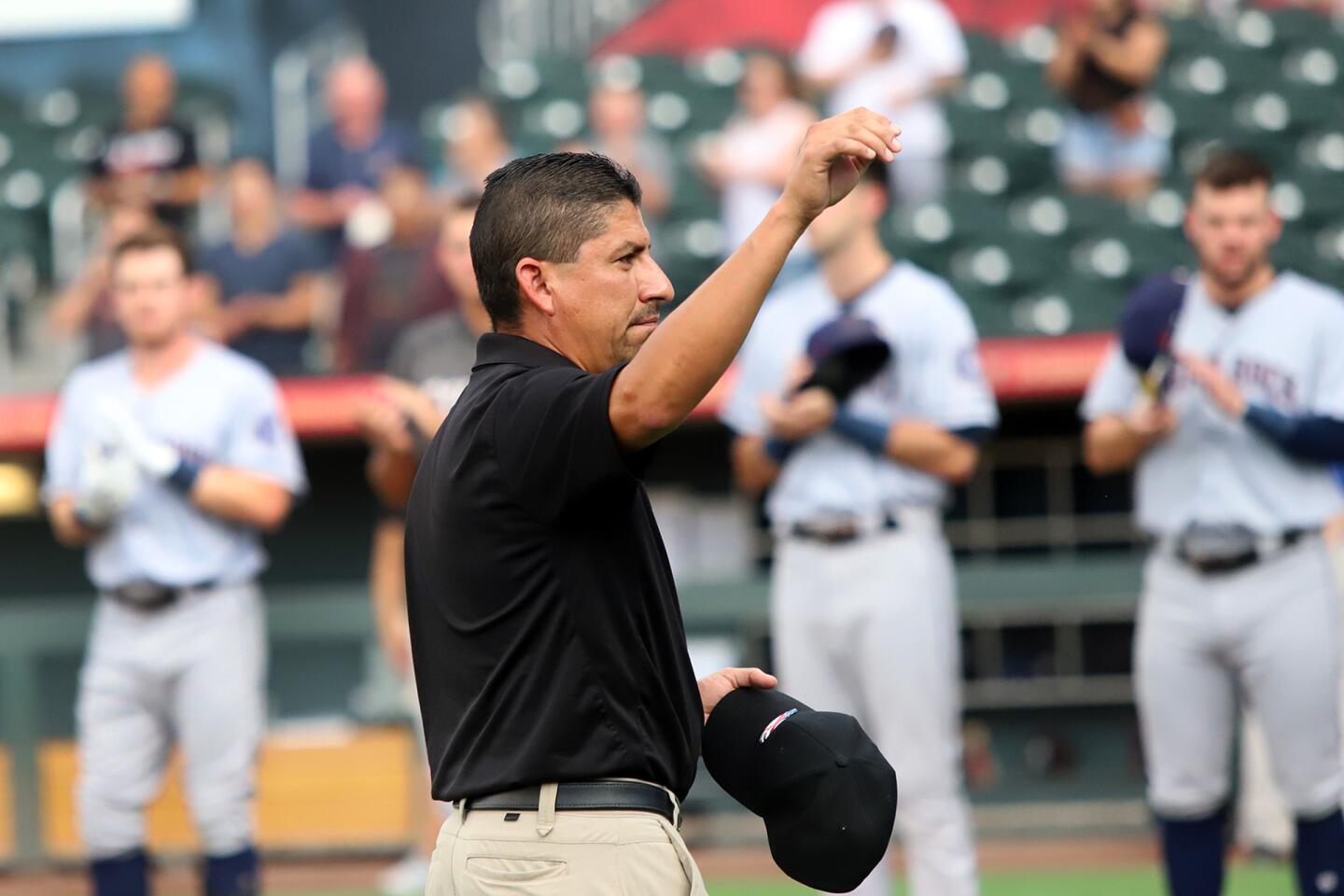

But now the father of five was standing on the field at the first home game for the El Paso Chihuahuas since the shooting. Chihuahuas players in black jerseys lined up along the third-base line, and the visiting Round Rock Express — in gray uniforms — stretched down the first-base line.

The El Paso team, a triple-A affiliate of the San Diego Padres, was honoring him for helping to save people from the shooter. One of the Chihuhuas’ team doctors gave him a small blessing. “I tried to get everybody out,” Evans told the doctor. The doctor gave him a hug. “It felt so comforting,” Evans said.

He choked up as the national anthem was played. When they had 22 seconds of silence in honor of the dead, one second for each, it was quiet except for an ambulance siren wailing in the distance. The names of each victim scrolled over the big screen over center field. In a moment that made him smile, a rainbow appeared beyond the stadium along the first-base side.

Travis Radke, a left-handed pitcher for the Chihuhuas, was emotional. He grew up in Thousand Oaks and used to go to the Borderline Bar and Grill regularly, and watched in horror last year as he learned of the mass shooting there that claimed the lives of 12.

Standing in the bullpen, he said that when the El Paso shooting happened, the team was on the road and all he wanted to do was to get back and help. Radke said he hoped that the game could give people a respite from the grief and pain for at least a couple of hours.

“Baseball has always been with us,” he said. “During World War I, World War II, 9/11 — it’s always been there. I hope people find some comfort in that.”

Evans did.

He took his seat behind home plate, along with wife Norma, his dad, John Evans, and other family members.

The familiarity was instant. The first baseman rolled warm-up grounders to second, shortstop and third. The players whipped throws back to him, the ball snapping into the leather — just as they always have since the days of Babe Ruth.

The stands were about half full and already some were wearing “El Paso Strong” T-shirts. Those words were stenciled behind the mound as well and flashed on the scoreboard throughout the game.

Emmanuel Ramirez hurled the first pitch, and it was fouled off into the seats. The Chihuahua mascot — a large dog — walked along the concourse and posed for pictures with kids. Lines for street tacos, hot dogs and beer had already begun to form. Ramirez gave up a two-run homer to put the Chihuahuas down 2-0, but in the bottom of the first, El Paso took the lead on back-to-back home runs.

Norma Evans rubbed her husband’s back. He ate popcorn and had a beer. The game seesawed back and forth. The Express had scored in every inning through five, and El Paso had scored in all but the second inning.

When in the fifth inning free T-shirts were thrown into the stands, Evans stood up and tried to nab one that sailed a few rows past him. There were the mid-inning promotions, including a race between a child and the mascot. A man had mixed results on a trivia contest shown on the scoreboard. During the game, Evans was engaged, coaching from his seat.

“Come on!” he yelled at a player who missed a cutoff throw.

He used to manage a youth T-ball team — and said he loves the teamwork baseball requires, which he says is applicable to so many parts of life. He likes teaching that lesson early to the younger kids.

But then sometimes during the game his mind wandered back to the shooting. A few employees from Walmart had also come to the game, and he would look at their faces and he’d be thinking about Saturday morning all over again.

One was in the money center and had helped take wounded out of the building. Another was in the cleaning supplies department, helping customers escape amid the gunfire. Evans remembered hugging one later. She told him he “looked like an angel running through the store,” he said.

It was his Walmart. He started there 21 years ago working in the dairy department, moving up to market grocery manager and ultimately becoming the store manager seven years ago. The attack felt personal and the wound felt deep. He refers to his store associates as a family, and El Paso has been his home for 42 years.

During the seventh-inning stretch, the crowd stood and sang. El Paso trailed 16-11. Some fans called it a night, leaving early. Evans and his family stayed. He’s an optimist.

“They’re still within striking distance,” John Evans said to his son.

Both booed the umpire for close pitches not called strikes for the Chihuahuas. They both shared analysis. “He was late on that,” Evans said to his dad after a player struck out swinging.

Radke came in for the top of the ninth inning, giving up four runs, and El Paso had a nine-run deficit to overcome. The first batter homered and Evans cheered. But the team lost, 20-12.

Evans and his family stood up and stretched as the remaining fans headed to the exits and out into the city. He hugged his wife, and his dad patted him on the shoulder. He looked tired as they headed to the exits and the dark night — and lightning flashing in the distance.

“I love baseball,” he said quietly.

And on this night, it loved him back.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.