Revered from left and right, she’ll soon be Canada’s longest-serving judge

- Share via

OTTAWA — Newspaper publisher Conrad Black, who disagrees with just about everything she does and believes, says, “she would get my vote as an ecumenical saint.” Alan Dershowitz, who disagrees with only most of what she does and believes, says he would “trade her for two American Supreme Court justices and a draft choice to be named later.”

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who probably agrees with her on just about everything, says she is “proud to count her among dearest sisters-in-law.”

Who is this figure who commands respect, reverence and regard from left and right; who has 39 honorary degrees from top institutions around the world; who was born in a displaced-persons camp in Germany to a mother who survived Buchenwald; who was one of five women in her University of Toronto law school class; who is about to become the longest-serving jurist in Canadian history; and whose theory of equality is one of the governing theses of law around the globe?

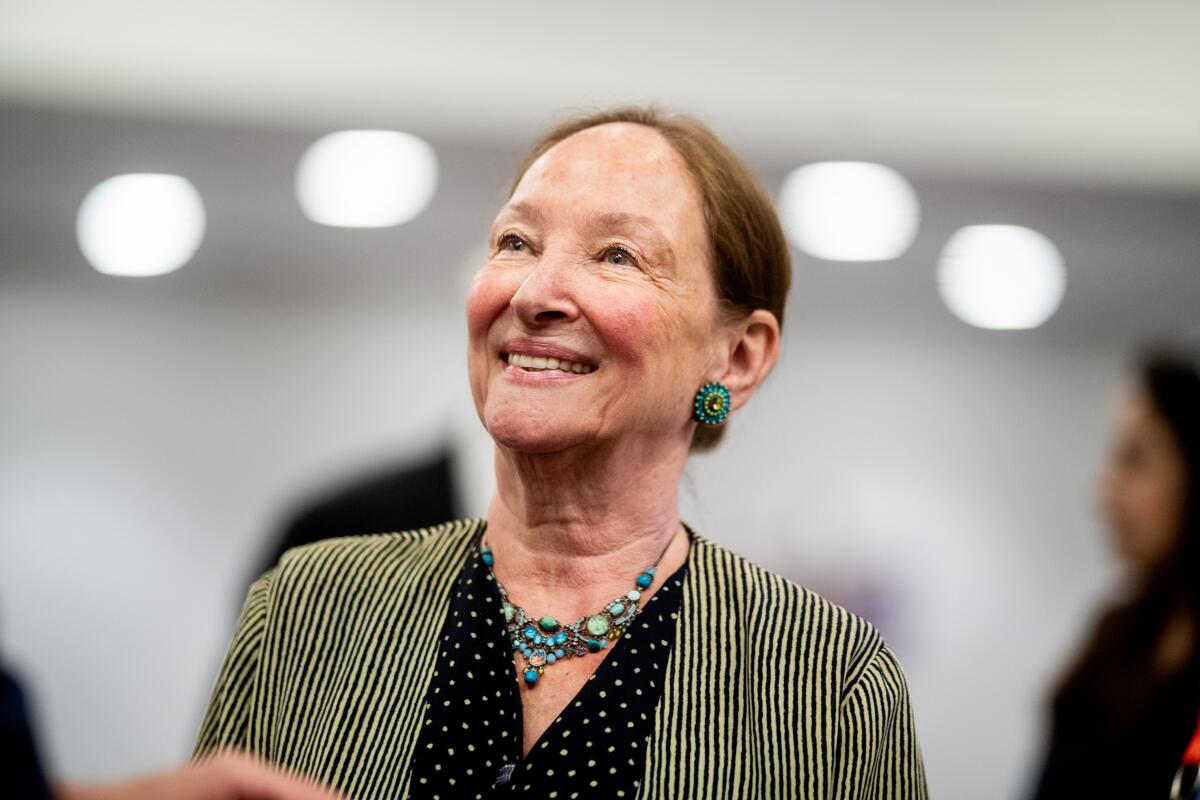

Meet Rosalie Silberman Abella, the most important Supreme Court justice you never heard of.

Actually, meeting Rosie — as petitioners and prime ministers alike call the 73-year-old jurist — isn’t as easy as it might appear. “See you at 9,” she emails her journalistic inquisitor, planning to meet her at Ottawa’s landmark Fairmont Chateau Laurier hotel, just a slap shot from the Canadian Parliament complex. “I’m easy to recognize — 5’9’’, blonde, and very skinny.”

Let’s try this again: Meet Rosie Silberman Abella, who measures in at barely 5-foot-2, is not blonde and probably once was very skinny. She may speak truth to power, but not in introducing herself to a visiting reporter.

At any height, Rosie Abella is a towering legal figure, quoted by politicians, cited by scholars, decried by critics and embraced by minorities, gays and the dispossessed who have relied on her as their vigilant and visionary champion.

Martha Minow, onetime dean of Harvard Law School, calls her work “pathbreaking.” Robert Post, former dean of the Yale Law School, salutes Abella as “a jurist who respects the rule of law and yet who understands that the purpose of the rule of law is to facilitate human flourishing.”

In many ways, she is a metaphor — her distinctiveness defining the differences between the American Supreme Court and its (distant) Canadian cousin.

The Supreme Court justice was treated for a tumor, her fourth bout with cancer.

“The two courts may seem similar, but the differences are substantial,” says Bernard J. Hibbitts, a former Canadian Supreme Court clerk and a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law. “The American court likes to think of itself as more stately and more grand.” The Canadian court, he adds, “is more willing to take into consideration international law than the American court, which is more insular.”

The American court can overturn laws, but in Canada parliaments can exempt some legislation from judicial review for up to five years. The Canadian court has four female justices, the U.S. court three. Justices are appointed by the prime minister and not for life. Unlike the U.S. court, it permits proceedings to be broadcast.

A member of the court since 2004, Abella is both a creature of the Canadian political and legal system and a molder of it.

Daniel Urman, a Northeastern University specialist on the U.S. Supreme Court, says, “Abella is Canada’s version of Sandra Day O’Connor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Thurgood Marshall: She was a pathbreaking ‘first’ in many dimensions.”

Above all, she is an activist, without the apologies American activist jurists now make. That, too, is a difference in the roles of the two North American high courts.

Until the 1980s, the Canadian court was a relatively passive participant in the constitutional process, largely because its jurisdiction was principally confined to the division of power between Ottawa and the provinces. But with the adoption of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, Canada went from being a parliamentary to constitutional democracy, and the emphasis of the court went from “being the arbiters of legal federalism to being the guarantors of human rights,” said Irwin Cotler, a former minister of justice.

Column One from the LA Times provides an inside look at special topics that deserve your attention.

“This happened not because the court sought that power,” he says, “but because the Charter invested that power in it.”

Since then, the Canadian Supreme Court, which once followed the U.S. Supreme Court, has been quicker to embrace change on core social issues, such as abortion, gay marriage and assisted suicide. The Canadian court also seems to have little trouble embracing cases and precedents from foreign jurisdictions.

“I just watch the rest of the world,” Abella says. “The Canadian Supreme Court has become the leading constitutional court in the world.”

When I was in first year Arts at [the University of Toronto] everyone told me to take a philosophy course with Professor Marcus Long. In the very first class he asked: “If a tree falls in the middle of a forest and no one hears it, does it still make a noise?” I turned to my best friend Sharon and said, “I’m outta here.”

— Abella, 2002

A chat with Abella is not so much a tennis match — the talk bouncing back and forth — as a pool game, the cue ball of conversation careening off the cushions, sometimes colliding with other balls. What starts with a story about buying pantyhose in Belfast dissolves into an aside about the books she has read lately and then into a digression on Lyndon Johnson. Before long the topic turns to what exactly is the Canadian character, and then to the vicissitudes of Ontario cottage country and then — how did we get across the Atlantic again? — to the canals of Venice.

Along the way, the conversation turns to her origins. Rosie Silberman was born in Germany on July 1 — a date now known as Canada Day, commemorating the 1867 confederation of Canada into a single entity in the British Empire — in the year after World War II ended.

Her parents were living in Stuttgart displaced-persons camp following a dramatic reunion. After the Buchenwald concentration camp was liberated, her mother, Fanny, learned her husband was still at the Theresienstadt camp, which had been quarantined because of a typhus epidemic. She found him after sneaking into the camp with a garbage detail.

By 1950 the family landed in a country so clean, so prosperous and so virtuous, at least compared with the charnel house of Europe, that in Auschwitz the lone quiet corner of the camp had been called “Canada.”

It was in the real, far more prosaic Canada — a country whose leadership, as F.R. Scott put it in an acidic 1957 poem, was satisfied to “Do nothing by halves/Which can be done by quarters” — that Abella flourished.

She was a pianist who practiced two hours a day, a student who devoured books, school valedictorian. Unlike her parents, eager assimilationists like so many of their Jewish peers, she knew nothing of anti-Semitism, nor of the more exotic, liberating creed of feminism.

As a teenager, she became determined to be a lawyer. Her role model was her father, who was about to take his exam to qualify as a judge when the Germans invaded Poland.

“He couldn’t practice in Canada because he wasn’t a citizen and ended up — happily and without complaint — as an insurance agent,” she says. “But Canada more than made it up to us with its extraordinary generosity.”

His daughter pressed on, crossing or, rather, crumbling, barriers that held back others. Until 1977, she never knew another lawyer who was a mother. But nor did she know much of the world’s woes.

“Notwithstanding my background, I thought the world was a piece of cake,” she says. “It was through my clients that I learned about sexism and racism.”

But then, pregnant with her second son, she became a family-court judge at 29, and acquired an intimate window into the margins of the culture that had shown her so much promise and privilege.

“Here I was, deciding whether other people’s babies should be removed from their parents when I had two of my own at home,” she says. “This was the hardest job I ever had, and where I learned how to listen. Every job I’ve had since started with my understanding of the world through the eyes of these people, who expected fairness, courage, an open mind — someone who listened and someone who was decisive.”

So it was no surprise when, in 1984, she produced a report on employment equity that Lorna R. Marsden, the retired president of York University in Toronto, says, “changed the nature of Canadian workplaces” by requiring all organizations receiving federal funding to file reports on their labor force by gender and the presence of disabled workers, visible minorities and indigenous people.

You cannot be born in the shadow of the Holocaust to two Jews who survived it, without an exaggerated commitment to the pursuit of justice. You cannot grow up indifferent to the rule of law when every adult you love experienced the horror of its subversion. And you cannot live a life without idealism when the very fact of your birth reflects a tenacious belief by parents whose only son had been one of the war’s 6 million martyrs to injustice, that the world would turn fairer.

— Abella, 2019

In the 1990s, while on the appellate court, Abella wrote a decision striking down a tax-law provision restricting Canadians to leaving their pension benefits to a spouse of the opposite sex. She in effect inserted two words (“or same”) between “opposite” and “sex.” As a result, pension benefits in Canada now can be left to a spouse of any gender.

In Abella’s world, two words can make a world of difference. And for the world of her, she cannot imagine why these sorts of issues are so hard below the 49th parallel.

“All of these issues remain an open sore in the U.S., but Canada moves on,” she says. “The American court and country seem to go conservative, then liberal, every few years, but Canada has been on a slow and evolutionary trajectory toward more inclusion, respect for diversity and respect for identity.

“It’s a trajectory,” she goes on, “but a consistently moderate trajectory.”

Her critics complain there is nothing moderate about it.

“She believes it’s a judge’s role to do justice rather than to follow the rule of law,” says Leonid Sirota, a senior lecturer at Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand and one of Abella’s most fervent critics. He adds, “In her conception, the law dissolves into what she thinks is right or wrong.”

Those same views have won her salutes in more liberal judicial circles worldwide. Listen in as she explains it in her Ottawa judicial chambers:

“The role of majorities is to elect legislators to make laws that are responsive to the majority. The role of an independent judiciary is to determine what the law is notwithstanding the wishes of the majority. We are not responsible to public opinion. We are aware of it. But that is the responsibility of the legislature. The attacks on the legitimacy of independent judiciaries around the world are attacks on their institutional responsibility — to take everything into consideration but not to be guided by the majority view.”

One of Abella’s animating ideas is that there are elements of religious practice that need protection.

“She has taken a strong interest in this area and has wanted to recognize the more communal and social dimensions of religion in a way some of the other judges were not sold on,” said Dwight Newman, a constitutional law scholar at the University of Saskatchewan. “Eventually her views have won out.”

This notion emerged in the 2009 Hutterite Brethren case, involving a religious colony that did not want its members photographed for Alberta driver’s licenses. The court ruled for the province, but in her dissent, Abella wrote that the ruling would be devastating to the community because, in its view, the license photo meant showing allegiance to the country and not to God.

Six years later, the court took up the Loyola High School case, involving a Jesuit school’s refusal to adopt Quebec’s Ethics and Religious Culture program. The court found for the school, saying Quebec infringed on its religious freedom by not letting it teach the program from a Catholic perspective.

In siding with Abella, Chief Justice Beverley Marian McLachlin, who was on the other side from Abella in the Hutterite case, basically conceded that the view of her fellow jurist had merit.

One of the psychological legacies of having a Holocaust background like mine is that you take nothing and none for granted. There is no sense of entitlement, only of grateful relief when luck merges happily with fate.

— Abella, 2004

In two years, under Canadian law, Abella must retire at age 75. She is filling the final portion of her court career with speeches and respites at her Ontario lakeside retreat with her husband, a prominent specialist in the Canadian labor movement and in the history of the Jews in Canada. And she continues laboring, in longhand, over pressing legal cases. In midsummer her credenza is full of separate piles, one for each case.

“She is always well prepared,” says former Justice Claire L’Heureux-Dubé. “She knows her file by heart.”

Her Supreme Court colleagues say Abella — no Silent Clarence Thomas of the North — speaks up during arguments, but only when she needs to. “She’s not the kind to pull the carpet from anyone and interrupt or impose her own ideas during hearings,” former Justice Marie Deschamps says. “She has a way of indicating what is on her mind — and sometimes not in the way lawyers would like.”

That quality marked the beginning of her career as a judge and remains with her as she approaches the end of her career.

But she is not in decline, nor even inclined to recline. More than ever she is drawn to her work, both vocation and avocation. She is a lifelong admirer of George Gershwin, and so two lines that are a pure distillation of American optimism from his 1931 Broadway show — “Of Thee I Sing” — might well be Abella’s legacy across the border:

Shining star and inspiration,

Worthy of a mighty nation.

Shribman is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.