China’s clear message to the U.S. on Hong Kong: Beijing will not back down

- Share via

In a devastating blow to Hong Kong’s long-promised autonomy, China has announced plans for a national security law that could squash protests and cripple freedoms in the territory. The move is also seen as clear signal that Beijing has no intention to bow to global opinion, even as it faces increasing pushback from the U.S. and other countries.

“China is now using the Hong Kong issue to send a crystal clear message to the U.S. that China will never back down on issues involving its national sovereignty and security,” a scholar with close connections to Beijing told the state-owned Global Times on May 21.

The U.S. government is ratcheting up pressure on China, further restricting its technology champion Huawei from getting the critical components it needs to survive and threatening to force its big enterprises to delist from exchanges. Calls are growing in the European Union to block Chinese firms from acquiring European ones. Russia and Turkey have joined in demands for an investigation into the origins of the pandemic, which after weeks of fierce opposition, China has finally accepted. Public opinion too has not been kind: about two-thirds of Americans now view China negatively, up 20 percentage points since Trump took office and the highest level ever recorded by the survey-taking Pew Center. The proportion of people who rate China positively has dropped by double digits in almost half of Europe’s countries.

Rather than abandon their recent “wolf warrior” approach to foreign relations and step back from their statist-economic inclinations, Beijing seems intent on doubling down on its hardline approach. While China may well soon announce more economic reforms to boost lagging growth, its officials are becoming more combative: getting even more angry at what they see as unfair international criticism as they gain increasing support from the Chinese people for their recent successful handling of the coronavirus; that stands in marked contrast to U.S. flailing, which they believe demonstrates the superiority of a more authoritarian system over Western-style democracy.

What’s behind the tough line? As COVID-19 infections and fatalities soar in the U.S. and Europe, even while the Chinese Communist Party overcame its initial blundering and moved to aggressively stop the virus spread, most Chinese have shifted from an initial period of grave doubts and anger at their own leaders to now praising them. Today the average urban resident is sure — and probably rightly so — that they are far safer living in Shanghai or Beijing, than New York or Washington. The flood of overseas Chinese students who fought for seats on planes to evacuate the U.S. and Europe and frantically return to their homeland only strengthened public support for the China’s leaders.

President Trump’s continuing erratic behavior on Twitter and in speeches has also changed perceptions of the U.S. and its leaders. Before Trump was commonly viewed as a practical and successful businessman who would place mutual economic interests over fractious political concerns, in favorable contrast to previous U.S. presidents (the fact that Trump has spectacularly failed in business isn’t well known in China where instead many know him from have watching his reality show on Chinese television.) But today he is mocked on Chinese social media as a buffoon and an embarrassment for the U.S.

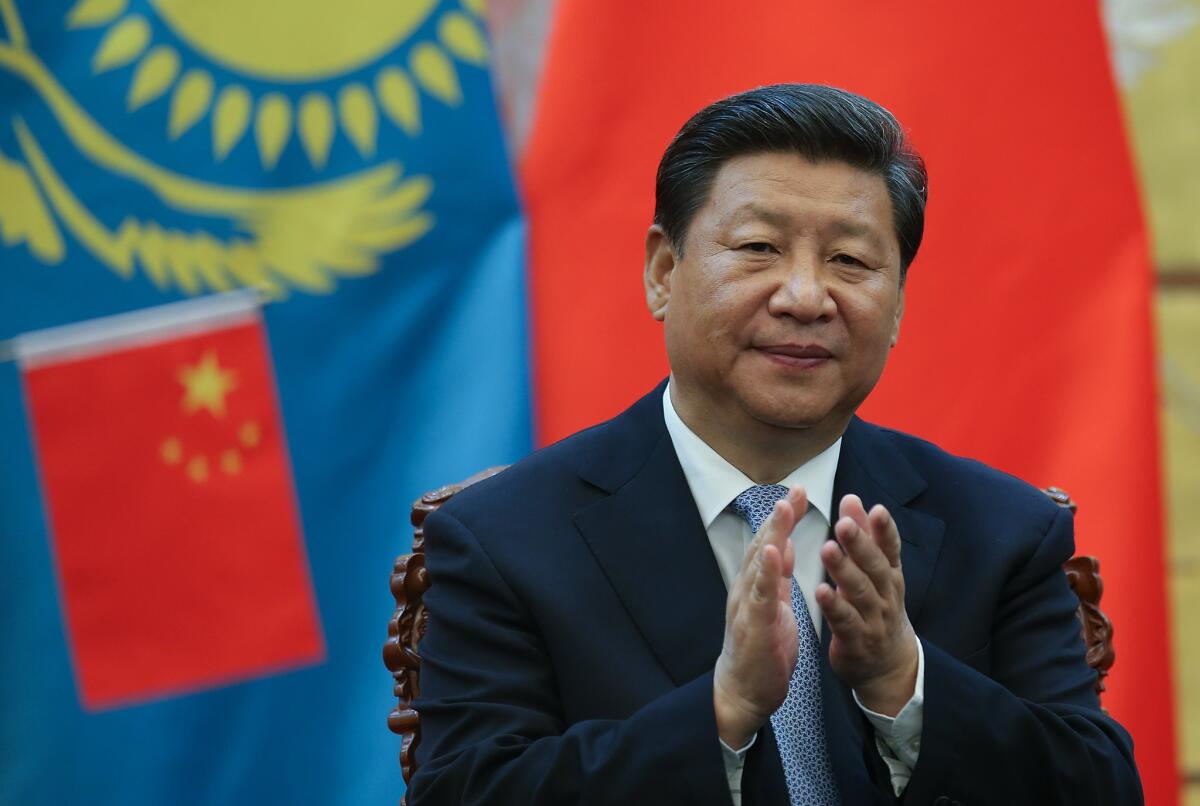

Meanwhile, the two-year long trade war, along with punitive actions taken against Chinese technology companies, efforts that seem calibrated to destroy their growing competitiveness, is seen as evidence that the U.S.’s ultimate aim is to block their country’s rightful rise to global power. They may be right: the bilateral tensions arguably are rooted in the unavoidable friction between a rising China, and what increasingly appears a declining U.S., a has-been superpower, that has no interest in ceding any ground. And that tension has only became apparent under the more assertive leadership of party secretary Xi Jinping, But recognizing the dilemma does little to resolve it.

What’s obvious is China has no intention to stop building up its own national champions, even when that means providing subsidies, favorable licensing and regulations, and guaranteed market share to companies such as Huawei, no matter how much the rest of the world calls foul. And while officials may no longer talk openly about it, as when they stopped publicly touting the Made in China 2025 plan to strengthen Chinese industry last year, the industrial policy approach hardly can be expected to go away. Indeed, China’s practice of tilting the playing field to benefit its own companies over non-Chinese multinationals started years ago.

While the official names may change — under Xi’s predecessor Hu Jintao the ambitious plan was called “indigenous innovation”— the target to build globally competitive Chinese firms remains a constant. Now that impulse towards self-reliance, what Xi Jinping and other leaders have called ziligeng sheng, has only strengthened: if you can’t count on the U.S. to provide semiconductors or the parts to make them, as has been made abundantly clear, all the more reason why China must quickly develop its own technology capabilities.

The Chinese public’s now evident support for its leaders and their policies could quickly fade, however. The populace have long accepted an implicit bargain: as long as the Party continues to guarantee rising living standards, the people will not demand civil rights or openly criticize authoritarian rule. But if economic growth severely stagnates, and already there are signs that unemployment could soar later in the year as companies go bankrupt and markets for China’s exports dry up, all bets are off.

A sustained downturn that would stand in stark contrast to the last few decades of average annual double digit growth in GDP, could quickly erode the bargain. Meanwhile, faith in the government is even more precarious for the other non-urban half of China, migrants and people in the countryside; even before the virus hit their livelihoods, they have not benefited from the system as those in the cities have, and have fallen on the losing side of China’s fast-growing wealth gap.

Still it is nonsensical to think that a fall in confidence at home equals admiration for U.S. leaders or acceptance of policies that work against national interests. Even when in the past it has been China’s own policymakers pushing to expose domestic business to more overseas competition, patriotic Chinese have reacted angrily, attacking them as bending to foreign demands. Similarly, most Chinese view Hong Kong as an integral part of China and feel that its residents are wrong to demand more freedoms.

The pride most Chinese have in their country is a real one and has only gotten stronger as the economy has grown to the world’s second largest. And China’s cadres have a long and successful track record of drumming up nationalism when times get tough: by directing anger at foreign governments, often the U.S. — a relatively easy thing to via the state-controlled media — they are able to take the heat off their own failings. We are likely to see more fanning of nationalism as the global economy deteriorates affecting China and anger towards U.S. policy will survive long after November, regardless who sits in the White House.

As the U.S. administration has bandied about the idea of demanding Beijing pay for pandemic-caused economic losses and waiving its sovereign immunity, irate comparisons to the colonial era have surfaced in China. Social media postings and news article in the state press has specifically compared today’s actions to those carried out by the Eight-Nation Alliance, including the U.S. and Britain, which forced the defeated Qing government to pay reparations after the 1900 Boxer Rebellion, a piece of historical ignominy taught to every Chinese child. As the U.S. and Europe demand more policy change from China, no matter whether justified or not, the likely response will be growing anger and a population ever more ready to push back. That is something the world had better get used to.

Dexter Roberts, author of the recently released “The Myth of Chinese Capitalism: The Worker, the Factory, and the Future of the World,” worked as a reporter based in China for over two decades, where he covered the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997 and the crackdown on freedoms that has followed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.