In Appalachia, coronavirus and race issues seem part of another America

- Share via

SOUTHEAST OHIO — The ice-cold water spills relentlessly into a concrete trough from three pipes driven into a hillside near the edge of town.

People have been coming to the trough for at least a century, since horses were watered here and coal miners stopped by to wash off the grime. People still come — because they think the water is healthier, or makes better coffee, or because their utilities were turned off when they couldn’t pay the bills. Or maybe just because it’s what they’ve always done.

As Tarah Nogrady collects water in plastic jugs to lug back home, she doesn’t wear a mask, like so many around here. Nogrady doubts that the coronavirus is a real threat — it’s “maybe a flu-type deal,” she says.

It’s a common view in the little towns that speckle the Appalachian foothills of southeast Ohio, where the COVID-19 pandemic has barely been felt. Coronavirus deaths and protests for racial justice — events that have defined 2020 nationwide — are mostly just images on TV from a distant America.

For many here, it’s an increasingly foreign America that they explain with suspicion, anger and occasionally conspiracy theories. The result: At a time when the country is bitterly torn and crises are piling up faster than ever, the feeling of isolation in this corner of Ohio is more profound than ever.

It’s easy to dismiss COVID-19 in these sparsely populated rural counties, some of which can still count their deaths from the disease on one hand. Local politicians hint that even the small death tolls might be inflated.

Deaths from COVID-19 in the U.S. reach 200,000 as authorities across the country continue to struggle to curb its spread.

Many of Nogrady’s neighbors think the pandemic is being used by Democrats to weaken President Trump ahead of the election. Some share darker theories: Face mask rules are paving the way for population control, they say, and a vaccine could be used as a tool of government control.

“I think they want to take our freedoms,” Nogrady says, a baseball hat turned backward on her head. “I believe the government wants to get us all microchipped.”

Southeast Ohio is where President Lyndon Johnson decades ago first mentioned the Great Society, perhaps the most audacious federal push to remake America since World War II. When Johnson gave his speech in 1964 at Ohio University, the hills of Appalachian Ohio were some of the most fiercely Democratic places in America.

“We must abolish human poverty,” Johnson declared, foreshadowing a torrent of federal programs that would eventually include Medicare, Head Start preschool, environmental laws and a push for equal justice.

These hills were then a patchwork of closed coal mines, undernourished children and houses without indoor plumbing. But applause surged through the thousands of people in the audience. They believed.

Former President Lyndon B.

Not anymore.

Now, except for the county of Athens, where Ohio University nurtures a more liberal electorate, the region is fiercely Republican. People who a generation ago believed in the president’s promises to change their region forever now have a deep distrust of Washington — and a defiant sense that they are on their own.

The idea that Washington can solve America’s problems is risible.

“It’s impossible!” said Phil Stevens, a deeply conservative Republican who speaks in exclamation points, then apologizes for doing so. “Ridiculous!”

Stevens, 56, runs a small auto-repair business and used-car lot in a narrow valley where his family has lived for generations. He talks about the anger and suspicion that thread through the hills, about a deep distrust of the government, about friends stocking up on weapons and ammunition. A former Democrat, he now derides the party as a rabble of left-wing extremists who won’t even stand up for police officers during riots.

“I fear our country’s not far from collapse,” he said. “We’ve taken it and taken it. And there’s going to be a lot of people that just ain’t taking it no more.”

The political ground of southeast Ohio began to shift decades ago. But in 2016, counties where Democrats once had sizable minorities swung hard to the right — part of a broader national wave of working-class regions that helped Donald Trump take the White House.

Trump was unlike any candidate they’d seen before. He was the perfect candidate for a region that not only expects little from the government, but also mistrusts it deeply. In many counties around here, Trump took more than twice as many votes as Hillary Clinton.

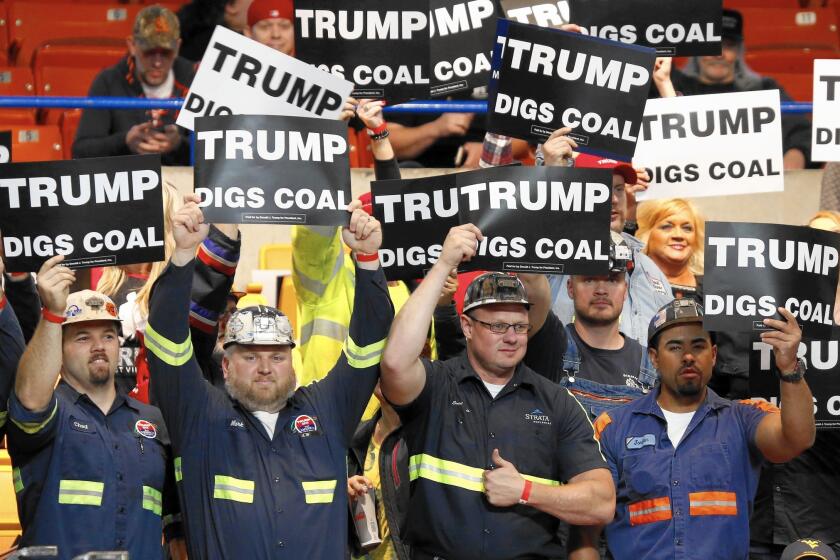

Despite Trump’s mostly failed promises to bring back coal, he’s still popular among many miners.

Rural Appalachians have long bristled at the way outsiders have portrayed them, replacing their complicated reality with stereotypes about poor and ignorant mountain people. Chris Chmiel, a small farmer and Democratic commissioner for Athens County, believes deeply in the benefits of Appalachian life: the fierce tenacity of its people, the beauty of the hills, the ties to hometowns and families in ways that are increasingly rare in America.

“We have a lot of things that other people don’t have,” Chmiel said recently at a weekly farmers market. “That is priceless in my opinion.”

Yet it’s impossible to paint a picture of this swath of Appalachia without describing its deep and pervasive poverty. It’s visible in the houses near collapse, the trailer homes fixed with duct tape, the buildings consumed by vines. These not-quite ghost towns, once thriving coal communities, are now slowly dying, leaving behind streams that still run a putrid orange from the drainage of old mines.

Although coronavirus deaths here are still relatively rare, its economic impact is widely felt. Unemployment skyrocketed to highs of nearly 18% amid early lockdowns, doubling in some counties from March to April. While those rates have come down since, nearly every county in the region is still worse off than at the start of the year.

Six months into the pandemic, businesses from used-car lots to barbershops to organic farmers are battered. Stevens has seen business plunge by 30% or more.

“We’ll tough it out,” he said. “We don’t make a lot of money here. But we learned to live on just a little.”

Many industries have taken a severe hit, but the state’s housing market should enjoy a quick recovery, a UCLA forecast predicts.

Like COVID-19, the other great story of today’s America — racial tensions and protests — is notable in this region for its absence. Black life is something most people simply don’t see in southeastern Ohio, where the 2010 census showed a Black population of less than 1% in many counties.

Around here, talk of protests against police brutality and Confederate statues immediately shifts to criticism of the violence at some protests. While there have been a handful of protests in the area, and most people will concede that America has racial problems, many also believe they are wildly exaggerated.

But things look very different in that small Black community.

Geoffrey West, 34, who runs a barbershop in Athens, still believes there’s plenty of racial misunderstanding, among both Black and white people, and he joined one of the handful of protests in the region against police violence over the past few months. He’s frustrated by white people who don’t see the reasons behind the protests.

“We need the police,” he said. But white people “don’t have a fear of walking out your front door and getting killed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.