How will I know when to get my second dose of COVID-19 vaccine?

- Share via

As health officials across the country try to get COVID-19 vaccines to people more quickly, it’s already time for some people to get their second shots.

Who’s keeping track to make sure that you get the correct second dose and that you get it on time?

It’s one of the many logistical issues that must be addressed to pull off the unprecedented vaccination campaign. The first COVID-19 vaccines available in the U.S. require two doses taken weeks apart. Other vaccines in the pipeline might not require two doses, but the record-keeping for those would work the same way.

The question of how many people must be vaccinated to reach herd immunity against COVID-19 is of crucial importance. Experts say the number is probably higher than previously thought.

Here’s a look at how COVID-19 vaccinations are being tracked, and who has access to the information.

What’s needed for my first shot?

When vaccines become widely available in coming months, the doctor’s office, health clinic or pharmacy where you get your shot will ask for basic information, such as your name, date of birth and gender.

You might also be asked for other information, such as your race and any health condition that could put you at higher risk for a severe case of COVID-19. But exactly what you’re asked will vary depending on where you go.

The shots are free, but you’ll probably be asked for your insurance information, if you have it.

Will I get a reminder for my second shot?

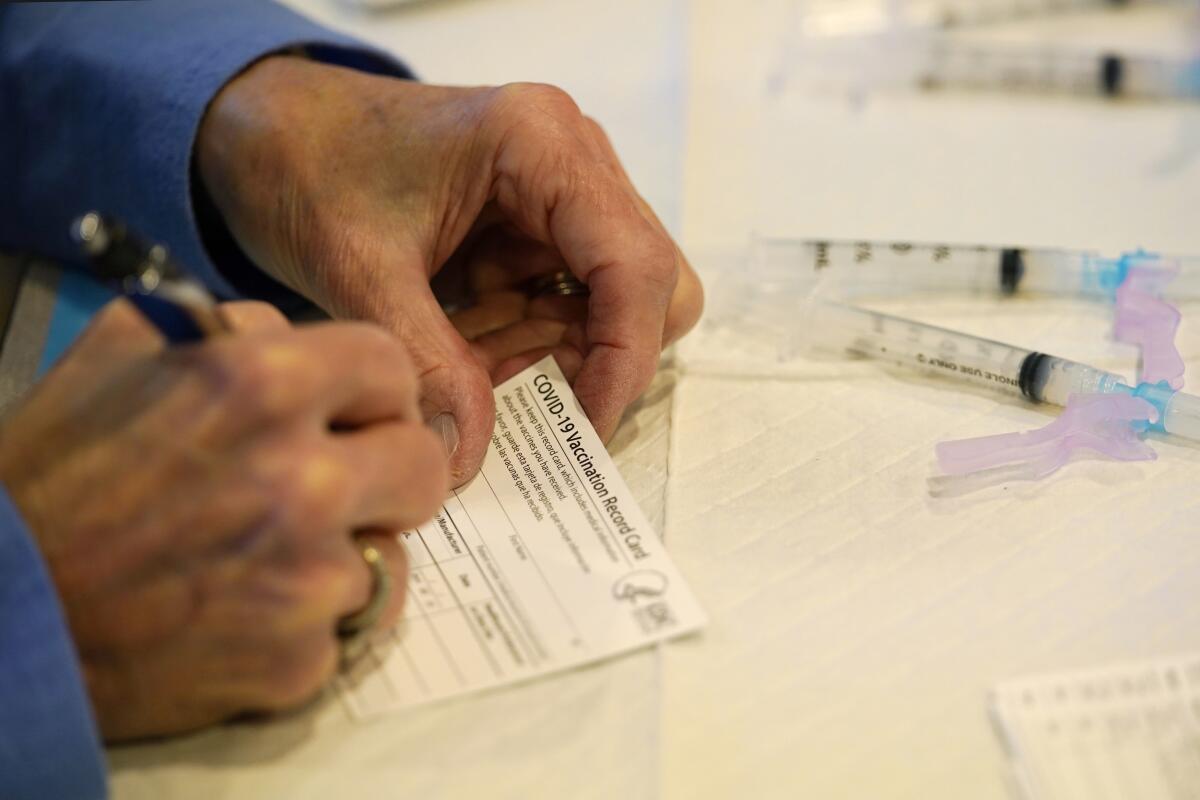

You’ll receive a vaccination record card saying when and where you got your first shot and what kind it was. Doctor’s offices, clinics and pharmacies will probably send reminders about the second dose; those could come by text, email or phone.

Doses of the vaccine made by Pfizer and BioNTech are supposed to be given three weeks apart, and doses of the vaccine developed by Moderna and the National Institutes of Health should be four weeks apart.

But the timing doesn’t have to be exact. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that doses given within four days of those targets are fine.

Will there be a record of my vaccination?

Providers should have a record of your vaccination in their system. They’ll also be entering the information into state or local immunization registries, which are used to record childhood and other vaccinations.

The registries will receive details such as which vaccine you received and when. That way, if you go to a pharmacy in another part of town for your second shot, workers there should be able to look up information about your first dose.

Local registries also will be feeding information to the CDC to give officials there a national picture of vaccination efforts.

What is being shared with the CDC?

That’s been a sticking point.

The CDC wanted information including names, dates of birth and gender of people vaccinated from local health officials. But many states pushed back, citing privacy concerns. They were still hammering out their data-sharing agreements in the final weeks before the first vaccine shipments went out.

Jon Reid, manager of the vaccine registry in Utah, said he expected most states to send data with personal information removed. But exactly what’s shared could vary.

“We have our own state laws that we need to be consistent with,” said Kevin Klein, director of Colorado’s Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management.

Americans’s interest in a COVID-19 vaccine is waning, with only 56% of adults saying they would get it if it were available. That’s down from 74% in April.

Philadelphia said it had agreed to share data on the ages of people who received vaccines, for example, but not names or birth dates.

“We are going to send them what we think is appropriate,” said Aras Islam, manager of the city’s vaccine registry.

The CDC had also requested information on people’s race and ethnicity. But some providers aren’t set up to collect that information, and it isn’t required, said Mitchel Rothholz of the American Pharmacists Assn.

Philadelphia says it’s asking providers to enter data on race and ethnicity if they can, and sharing that with the CDC. The city says that about 80% of cases so far include that information and that the percentage is expected to climb.

Why does the CDC want my vaccination information?

Federal officials say they need it to track vaccination efforts nationally and to identify regions or groups that might need more shipments.

To do that, the CDC says it will feed data without identifying details into a program called Tiberius. It’s not yet clear what insights the program will be able to offer, given the changes states made to their data use agreements.

“There will be some data variability, and we’re working through that analysis right now,” Army Col. R.J. Mikesh, the technology lead for the federal government’s COVID-19 vaccine development push, said previously.

Officials with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services haven’t detailed what information they plan to make public or when.

How will data be protected?

Vaccination information from states and cities will go into a CDC data repository called the COVID-19 Clearinghouse, which will “encrypt and store” the information, according to a data agreement sent to states.

The agreement says that the CDC will “take all reasonable measures to secure” the data and that the agency won’t be able to access any personally identifiable information without the permission of local jurisdictions. Federal health officials have said the data could also be useful if people happen to be in another part of the country for the second shot.

But without more details on how data might be secured, Islam in Philadelphia said the city opted to share information without any identifying information.