50 years after Attica prison uprising in New York, families still waiting for apology

- Share via

BUFFALO, N.Y. — Fifty years after the revolt at the Attica Correctional Facility, unanswered questions still bother those touched by what remains the nation’s deadliest prison uprising.

What unknown details are buried inside hundreds of pages of records that remain sealed?

And will New York state ever apologize for the pain caused by both the initial riot by inmates and the bloody massacre committed by police and guards as they retook the prison?

“I have gone through seven governors now, asking for an apology,” said Deeanne Quinn Miller, whose father, William Quinn, was the only guard fatally injured by inmates during the siege at the overcrowded maximum-security prison in rural western New York.

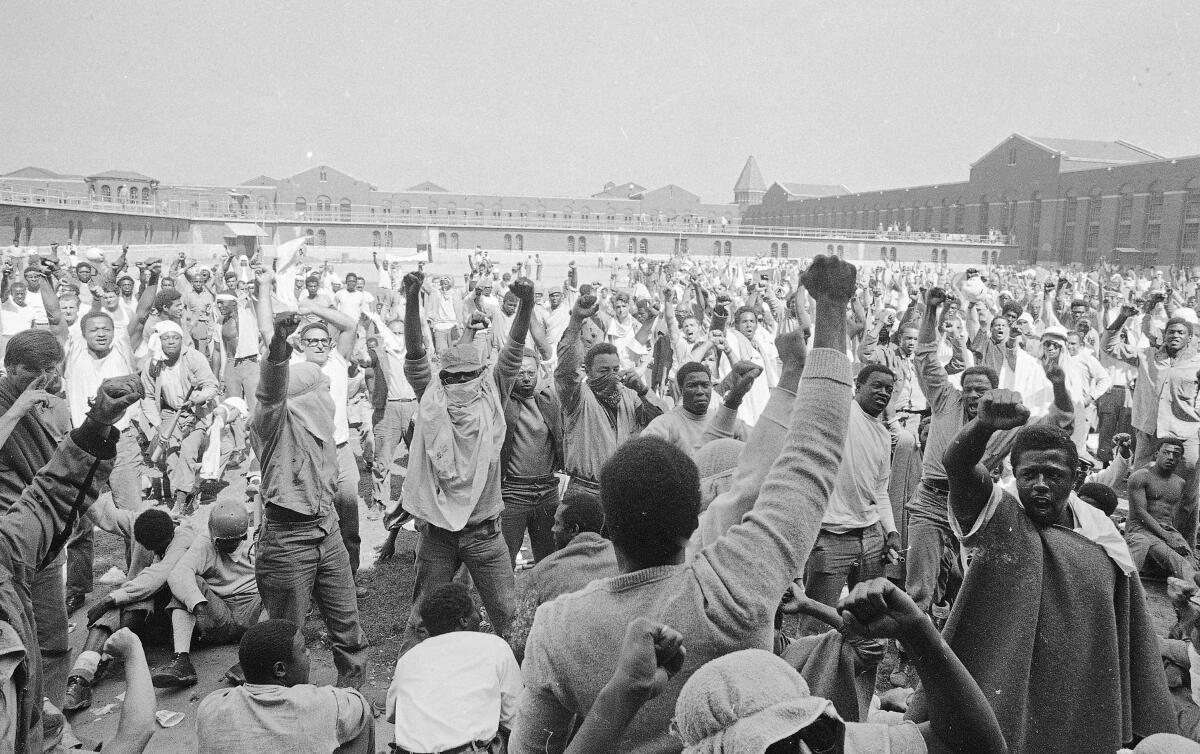

The Attica uprising began Sept. 9, 1971, when inmates upset over living conditions seized control of part of the prison and took staff members hostage. It ended four days later, when state troopers and guards shot tear gas into a prison yard, then fired hundreds of rounds into the smoke over the span of six minutes.

The gunfire killed 29 inmates and 10 hostages.

State officials initially claimed, falsely, that prisoners had slashed the throats of hostages as police began storming the prison, and news reports at the time quoted those false accounts. But autopsies a day later found that all the hostages had been shot by their would-be rescuers. Accounts of prisoners having castrated a guard also later proved to be false.

In all, 11 staff and 32 inmates died in the riot and siege. No law enforcement officers were put on trial for their roles in the massacre.

An apology seemed like perhaps the easiest of five demands that Miller and other members of the Forgotten Victims of Attica sought from the state after organizing in 2000 as a voice for slain and injured prison employees and their families.

Their other demands have been met: for financial restitution, counseling, permission to hold an annual ceremony on the prison grounds and the unsealing of riot-related records, although some containing secret grand jury material remain locked.

Any fear of liability that may come with an apology seems moot, Miller said, after a $12-million settlement with the Forgotten Victims in 2005 and an $8-million award to inmates and their survivors.

“I’m tired,” said Miller, who chronicled the uprising’s lifelong personal impact in a new book, “The Prison Guard’s Daughter.”

“I think it’s particularly poignant that it would come on the 50th,” Miller, who was 5 when her father was fatally beaten, said by phone. “When a person hears ‘I’m sorry,’ and it comes in a way that is genuine and authentic ... you feel like maybe somebody really does care about these state employees and these families that gave everything they had with very little in return.”

Gov. Kathy Hochul‘s office did not immediately respond to questions about whether she might consider apologizing on the state’s behalf. Hochul grew up in western New York and once represented Wyoming County, where the prison is, in Congress.

Former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, whom Hochul replaced in August, would not apologize, nor did three other former governors who held office while the request was pending: David Paterson, Eliot Spitzer and George Pataki.

The annual commemoration on the prison’s front lawn is scheduled for Monday.

State Sen. Zellnor Myrie has proposed legislation allowing for the release of certain grand jury proceeding materials “on the basis of enduring historical importance.”

The Brooklyn Democrat’s bill, which stalled last year, does not specifically refer to the Attica case but Myrie has noted that grand jury proceedings after the uprising resulted in numerous indictments of prison inmates but not against law enforcement.

Supporters point to the release earlier this year of transcripts of grand jury proceedings in Atty. Gen. Letitia James’ investigation into the March 2020 death of Daniel Prude, who died after being detained by police in Rochester. It was the first time in New York history that grand jury proceedings in a death caused by police were made public.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.